Amid the racist darkness of the 1930s -- an era when bigotry against African-Americans may have been worse than under slavery, and when the vast majority of white Americans collaborated in their systematic subjugation -- W.E.B. Du Bois kept alive the memory of another day and another social order. "The unending tragedy of Reconstruction," wrote the legendary black intellectual, "is the utter inability of the American mind to grasp its real significance, its national and world-wide implications ... This problem involved the very foundations of American democracy, both political and economic."

These words not only serve as the epigraph to Columbia University historian Eric Foner's new book "Forever Free," they are the clarion call Foner has spent his whole career answering. Foner may not possess the pop-culture appeal of Harvard professor Howard Zinn, but he is without doubt the other important radical historian of the American academy. If Zinn's specialty is the grand, sweeping generalization -- the idea, more or less, that everything you think you know about American history is wrong -- Foner's work has remained tightly focused on the contentious idea of freedom, that amorphous concept that has meant so many different things to so many Americans. (Among the titles of his 13 books are "Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men," "Nothing but Freedom," "Freedom's Lawmakers," "The Story of American Freedom," "Give Me Liberty!" and now "Forever Free.")

Foner's field of special expertise is what might be called without exaggeration the crucible of American freedom: the Civil War, the emancipation of the slaves and the ambiguous, myth-shrouded period that followed known as Reconstruction. He never puts it this directly, either in this new, somewhat compressed popular history or in his 1988 magnum opus, "Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877," but he sees Reconstruction, with all its contradictions and unrealized possibilities, as the key to all of American history.

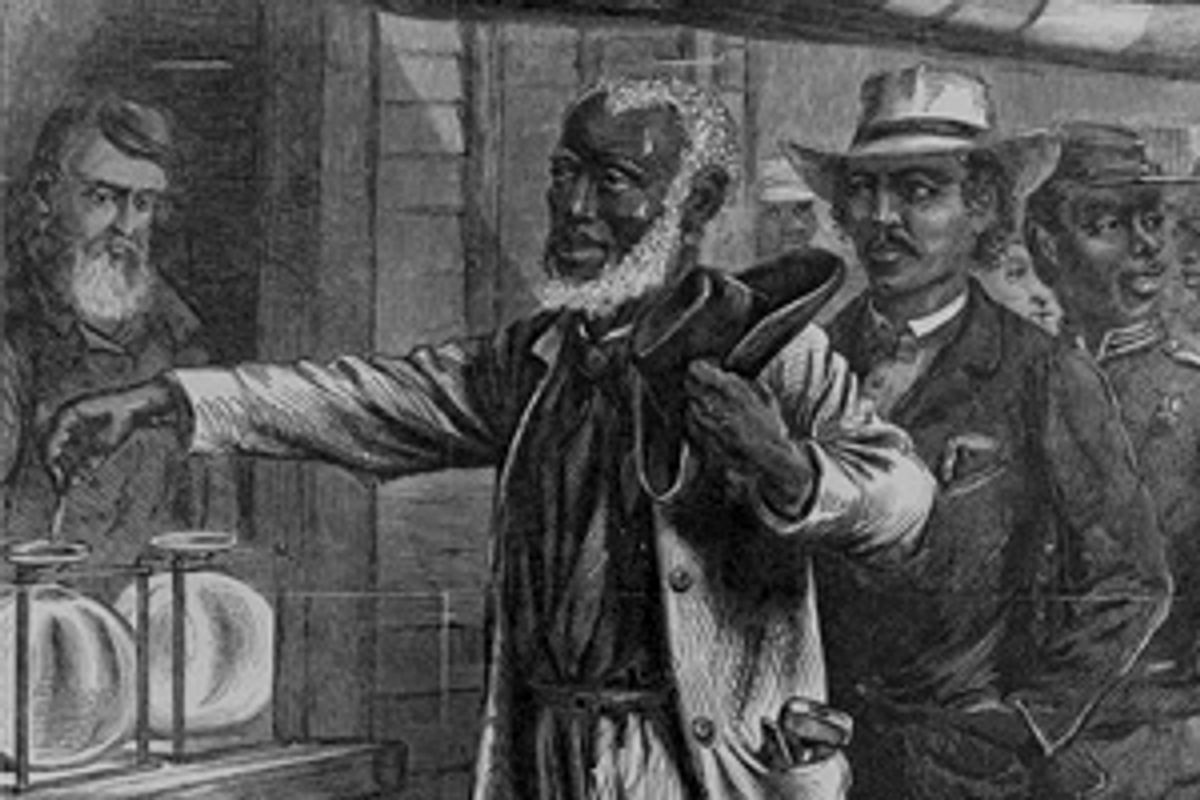

Given the many thousands of words Foner has already devoted to the topic of Reconstruction, the existence of "Forever Free" requires a little explanation. It was originally intended to be the companion volume to a television series that has yet to be produced; the residue of that project can be seen in Joshua Brown's interpolated "visual essays," which explore the changing representations of African-Americans and race relations throughout the period. To avid readers of history, there isn't much here that's dramatically new, but as a cogent and gripping account aimed at a wide audience, "Forever Free" fills a valuable niche.

More than that, this stripped-down narrative makes the long-term resonances and contemporary significance of Reconstruction more apparent than ever. One should be cautious about drawing parallels between the vastly different societies of America in 1865 and America in 2005 (and Foner never does so directly). But in both cases, we see a society so sharply divided along racial and cultural lines that it encompasses opposing and indeed incompatible worldviews. Undoubtedly it's simplistic to reduce the now trite "red-vs.-blue" division of the 21st century to an extended Civil War hangover, but it's not completely misguided either.

The age of emancipation and Reconstruction saw an explosive collision between federal and state power, and between Congress and the White House. It saw the federal government intervene in local affairs to serve as the protector of a persecuted minority group's civil rights, and saw local regimes of low taxation and limited government used as a smokescreen for reestablishing white supremacy and traditional oligarchy. Along the way, it remade the landscape of electoral politics, shaping both major political parties into recognizable precursors of their modern selves. And as Du Bois tried to remind the 20th century, it asked still-unanswered questions about whether freedom for African-Americans -- or any other Americans -- signified more than the freedom to sell their labor rather than have it beaten out of them.

Whatever else it was, the period of a dozen or so years after the Civil War was one of incredible political drama, unlike anything else in our history. Four million newly minted United States citizens, who had been other men's chattel months earlier, were thrust into the historical and political limelight. In alliance with both the "radical Republicans" of the North and a surprising array of Southern whites, they tried to build a biracial democracy on the ruins of a slave society. The legacy of this revolutionary experiment -- more revolutionary than any social change ever effected in the U.S., before or after -- has been debated ever since. Indeed, it was debated extensively at the time, and its participants were aware that it cast the notion of American freedom into sharp relief. In the words of Abraham Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation, the former slaves were to be "then, thenceforward, and forever free." But what did that mean?

Leaving aside the question of how to understand Reconstruction, its basic facts are astonishing enough. After the surrender of the Confederacy and the assassination of Lincoln, the Republican majority in Congress was (at least briefly) determined to crush the spirit of Southern rebellion and provide full citizenship to the freed slaves. Waging a ferocious battle against President Andrew Johnson (whose vision of Southern Reconstruction was, to put it gently, less ambitious), Congress drove through the 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments to the Constitution, enshrining the concept of universal equality before the law in that document for the first time. That extraordinary Washington conflict reached its climax in 1868, when Johnson was impeached by the House and avoided removal from office by a single vote in the Senate.

Whether newly emancipated or free-born, African-Americans flooded into the political and civic life of the Reconstruction South with prodigious enthusiasm. Many of the social organizations that had persisted underground under slavery, such as the black churches, black schools and black social organizations, became legitimate for the first time. (A fair number of these Reconstruction institutions, such as the traditional black colleges and the African Methodist Episcopal Church, remain prominent in African-American life today.) Within a few years, a middle class of black preachers, doctors and other professionals had begun to emerge, partly because of existing disparities in wealth and education between free blacks, rural plantation slaves and urban domestic slaves (some of whom had led relatively privileged lives).

These are the most energizing sections of Foner's propulsive narrative: Even white Southerners with openly racist attitudes and allegiances to the defeated aristocracy were struck by black Americans' appetite for literacy, political discourse and civic engagement after emancipation. "You never saw a people more excited on the subject of politics than are the Negroes of the South," wrote an Alabama plantation overseer in 1867. "They are perfectly wild."

Upward of 2,000 African-Americans were elected or appointed to office across the South before Reconstruction had run its course, a number not matched for more than a century afterward. These included the first two black U.S. senators, Hiram R. Revels and Blanche K. Bruce, both of Mississippi (with Revels actually taking the Senate seat that had been abandoned by Jefferson Davis), and the wonderfully named Pinckney B.S. Pinchback, who served briefly as governor of Louisiana amid the chaos of that state's 1872 gubernatorial election. Far more important were the many hundreds of black men who served as sheriffs, magistrates, constables, county supervisors and other local officials across the region; it was their prevalence that made hostile whites believe that they were living through "a terrifying social and political revolution," or as hostile later historians would put it, a botched experiment in "Negro rule."

In fact, high office was almost universally reserved for whites throughout Reconstruction, and while several states had black electoral majorities or near-majorities, only South Carolina ever had a black majority in its state Legislature. That state's African-Americans, in fact, consistently called for the most radical and sweeping reforms during Reconstruction (including the confiscation and redistribution of plantation land), which may be why they had to endure an especially repressive segregationist regime in later years. Across the South, the Republican Party remained an uneasy coalition between freed slaves, free-born blacks, Northern "carpetbaggers" and Southern white "scalawags," which mostly meant small farmers and other less affluent whites who had little attachment to the antebellum slave economy.

Reconstruction governments were often awkward and plagued with problems that would draw the eager attention of later scholars. But there can be no doubt, Foner insists, that "the appearance of African Americans in positions of political power a few years after the end of slavery represented a truly radical transformation in Southern and American history." By the early 1870s, he goes on, "biracial democratic government, something unprecedented in American history, was functioning throughout the South," and "the old planter elite had been evicted from political power."

As one South Carolina legislator would put it in a later memoir: "We were eight years in power. We had built schoolhouses, established charitable institutions, built and maintained the penitentiary system, provided for the education of the deaf and dumb ... rebuilt the bridges and reestablished the ferries. In short, we had reconstructed the State and placed it on the road to prosperity." Even Foner admits this is too rosy a portrait. Some Reconstruction governments were corrupt, although not exceptionally so by 19th century standards, and the Republican Party became increasingly divided by factional infighting, sometimes between blacks and whites and sometimes between radicals and moderates.

What was even more important, and not much discussed by later scholars hostile to Reconstruction, was the fact that the Southern experiment in biracial democracy came under violent attack from virtually its moment of birth. Various counterrevolutionary white militia groups had emerged by the late 1860s; the best known of them, of course, was the Ku Klux Klan. Klansmen and similar "night riders" murdered dozens of black public officials, burned out freedmen who had purchased "white land," and frequently assaulted whites who spoke out for equal rights, taught blacks to read or simply voted Republican. By some accounts the Klan murdered 1,300 people during the 1868 election campaign; Foner calls the Reconstruction-era Klan "the most extensive example of homegrown terrorism in American history."

President Ulysses S. Grant moved aggressively to crush this white terrorist resistance in the early 1870s, using the far-reaching powers granted him by the Ku Klux Klan Act of 1871. Indeed, the Bush administration's Patriot Acts were self-consciously modeled after the KKK Act, which responded to a perceived national emergency by federalizing a whole range of criminal offenses and suspending the writ of habeas corpus. The Nation, then as now a liberal newsweekly, complained about the unprecedented expansion of federal power. But the KKK Act also looked forward to the civil rights legislation of the 1960s. "If the federal government cannot pass laws to protect the rights, liberty and lives of citizens," asked former Union Army Gen. Benjamin Butler, "why were guarantees of those fundamental rights put in the Constitution at all?"

Foner, in fact, doesn't quite give Grant his due. As a leading exponent of the radical reassessment of American history, Foner tends to steer away from the deeds of Great Men and focus instead on mass movements, local organizations and community leaders we're unlikely to know about. This is all to the good when it foregrounds stories like those of John R. Lynch, a former slave who became a Louisiana justice of the peace and influential memoirist, or Abram Colby, a Georgia legislator who was abducted by the Klan and whipped viciously before his wife and daughter. The Klansmen asked him, "Do you think you will ever vote another damned radical ticket?" He assured them he would vote Republican till the day he died. "They set in and whipped me a thousand licks more."

But Grant, so often derided by later historians as a drunkard and incompetent -- judgments more recently called into question -- was almost certainly the last president before Dwight Eisenhower to behave as if the federal laws mandating racial equality actually meant something. (It may not be an accident that both men had experience commanding black troops in combat.) Grant was apparently given to vulgar racial talk in private life, but it's reasonable to assume that African-Americans preferred a president who called them ugly names but crushed the Klan to the many who followed, who said polite things about "the Negro" but tolerated vicious regimes of white supremacy and racist violence.

In the North, political leaders were increasingly concerned with the rising power of labor unions and the resulting workplace strife, developments fueled by a major influx of new immigrants from poor European countries like Ireland, Italy, Poland and Russia. As the Democrats began to identify themselves more and more distinctly as the party of the white working class, moderate Northern Republicans became the party of stability and order, identified with affluent WASPs and big business. In this context, the enduring turmoil and racial discord of the South seemed like a distraction, even an embarrassment. By the mid-1870s, the abolitionist generation of radical Republicans had left the stage, Grant's administration was embroiled in scandal, and both parties were eager to restore what was deemed normalcy to the South.

Five years ago, we heard a great deal about the the disputed presidential election of 1876, in which Republican Rutherford B. Hayes was declared the winner despite receiving 250,000 fewer votes than Democrat Samuel Tilden. As part of the final compromise that put Hayes in the White House, Tilden extracted a promise that federal troops would be withdrawn from the South and full local autonomy reestablished. In practice, this meant that political control of the region rapidly reverted to white Democrats, and more specifically to the same tiny class of wealthy white landowners who had dominated the South before the Civil War. In some areas, blacks continued to vote, and black Republicans continued to hold office, as late as the 1890s. But Reconstruction was over, and a long, dark period in American history was just beginning.

What lay ahead were the Jim Crow segregation laws, the rise of widespread lynching and the reborn "homegrown terrorism" of the Klan, often acting as a de facto arm of local government. For African-Americans, the age of freedom promised after emancipation was delayed for almost a century, until the "second Reconstruction" of the civil rights movement.

By the dawn of the 20th century, disenfranchising blacks and defunding black schools and other government services was official policy throughout the South. Laws mandating poll taxes, literacy requirements and other hurdles never mentioned race (and so were held not to violate the 15th Amendment), but their expressed aim was to "reduce the colored vote to insignificance," as a Charleston, S.C., newspaper put it. Louisiana's 1890 Constitution, for example, reduced the number of black registered voters from 130,000 to around 1,000 (and also disenfranchised about 80,000 poor whites).

Many of the "Redeemer" Democratic state governments of the late 1870s and after sound strikingly like today's Republicans, at least on fiscal issues. They took office promising massive cuts in taxes and spending, which served the dual role of helping rich planters and merchants retain their fortunes and denying education, healthcare and other services to the blacks and poor whites who had most likely voted Republican. Reconstruction schools had generally been segregated, but South Carolina, for example, had expended the same amount per student regardless of race. By 1895, white students were receiving three times the per-capita resources as blacks, a trend that would worsen dramatically in years to come.

By the time Du Bois published his prophetic book "Black Reconstruction in America" in 1935, white historians almost unanimously regarded Reconstruction as a disastrous and illegitimate experiment, concocted by wild-eyed Northern radicals and carried out by incompetent Southern blacks. If certain things about the Jim Crow era were regrettable (the argument went), white rule was nonetheless necessary, largely because of the innate "negro incapacity" to overcome childish ignorance or lustful passions. Foner cites Columbia professor John W. Burgess, one of the founders of American political science, who explained that blacks "were a race of men which has never of itself succeeded in subjecting passion to reason, and has never, therefore, created any civilization of any kind."

Needless to say, today's academic world is much closer to Foner than to Burgess. Ever since Kenneth M. Stampp's 1967 "The Era of Reconstruction" began to rehabilitate the radical Republican perspective, historians have quibbled over the details rather than the bigger picture. Reconstruction is portrayed as a noble experiment, perhaps naive or poorly executed, that challenged the nation to live up to its purported ideals. Disagreements exist over the roles played by Lincoln and Grant, or whether the radical approach of Northerners like Charles Sumner and Thaddeus Stevens -- who wanted the Southern aristocracy broken up and dispossessed -- was preferable to the more conciliatory and legalistic strategies of moderate Republicans North and South.

But Foner is arguably less concerned with his colleagues' views than with the currents of folk memory and public opinion -- which he says keep alive the negative stereotypes of Reconstruction -- and with the way the period permanently altered Americans' notions of freedom. African-Americans understood that concept, he argues, in a way that had been shaped by the experience of slavery and the forceful rhetoric of underground preachers who drew heavily on the biblical story of Exodus. Freedom was to be more an existential condition than a statutory one, a liberation of mind, body and spirit that would right the wrongs perpetrated upon an entire race across three centuries of bondage and torment.

Out of this understanding grew the call for "40 acres and a mule" envisioned under Gen. William T. Sherman's famous Field Order 15, the demand for slave reparations after the Civil War (a movement that remains alive today), and the vision of what is now known as affirmative action. Foner clearly believes that all these were morally justified, and that the American South would be an unimaginably different place today if the freed slaves had indeed been granted land ownership along with the means to work it. In that sense, he understands Reconstruction as a tragic missed opportunity to create real racial justice.

Beyond that, Foner rejects the now-standard progressive narrative of American history, in which emancipation and Reconstruction mark "the logical fulfillment of a vision originally articulated by the founding fathers." Indeed, as he says, the original Constitution never mentions the concept of equality, and "limiting the privileges of citizenship to white men had long been intrinsic to the practice of American democracy." Reconstruction, he continues, was "less a fulfillment of the Revolution's principles than a radical repudiation of the nation's actual practice of the previous seven decades."

American political culture of the 19th century, Foner writes, rested on federalism, limited government, local autonomy and deeply rooted ideas about the superiority of whites to blacks and men to women. These were the political values so dramatically reasserted when the Redeemers came to power after 1877, and it's not unfair to suggest that, however they may have been rhetorically modulated in recent years, they remain the values of the white Christian Southern majority today.

During the protracted battle with Congress that led to his impeachment, Andrew Johnson protested that the Reconstruction ideals that blacks were entitled to civil equality, and that the federal government had the power to define and protect citizens' rights, violated "all our experience as a people." Foner thinks he was right. Americans have never resolved the conflict between these radically opposed visions of freedom: the egalitarian model of republican citizenship on one hand, the hierarchical model of localized independence and self-government on the other. Based on the political landscape we see around us, 130 years after the end of Reconstruction, we never will.

Shares