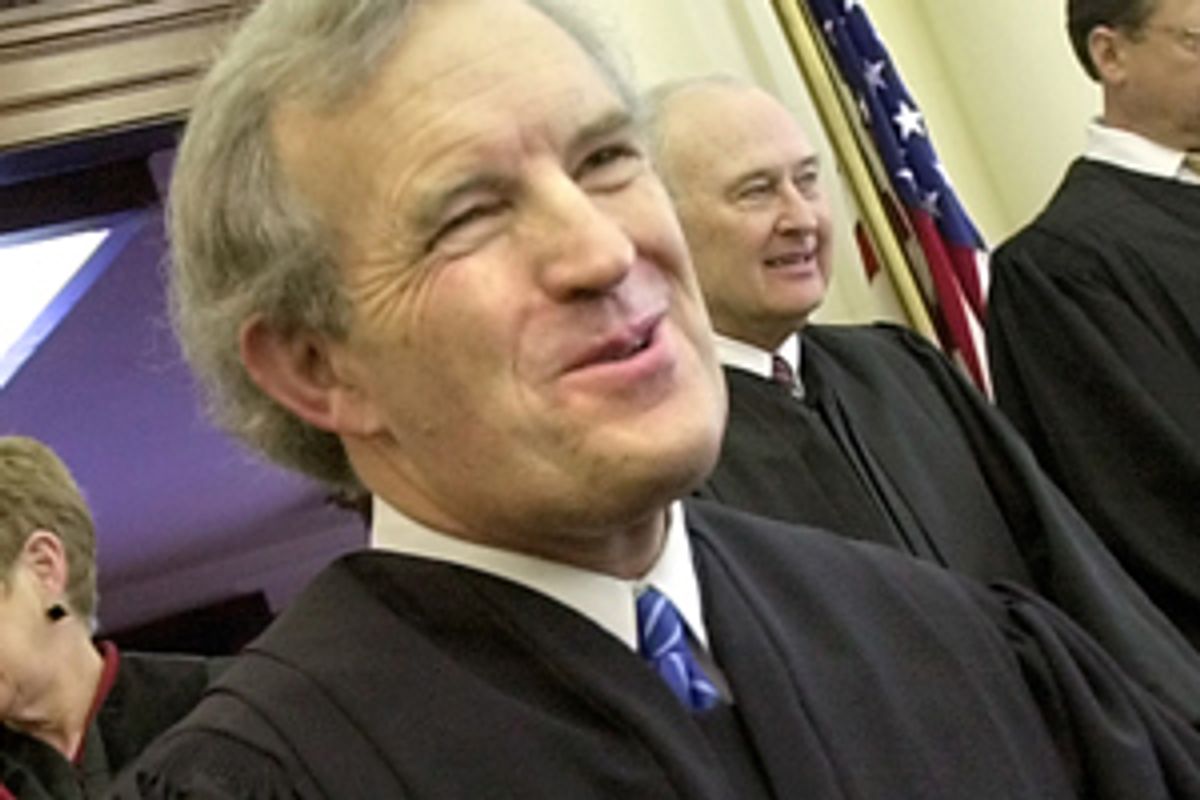

A judge nominated by President Bush to one of the highest courts in the nation apparently violated federal law repeatedly while serving on the federal bench. Judge James H. Payne, 64, who was nominated by Bush in late September to join the 10th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, based in Denver, issued more than 100 orders in at least 18 cases that involved corporations in which he owned stock, a review of court and financial records shows.

Federal law and the official Code of Conduct for U.S. judges explicitly prohibit judges from sitting on cases involving companies in which they own stock -- no matter how small their holdings -- in order to uphold the integrity of the judicial system. (Judges' financial filings typically don't differentiate ownership between the judge and immediate family members.) The clear-cut, objective standard aims to prevent even the appearance that a judge may be taking into consideration his or her personal financial interests.

Payne's financial filings show holdings of up to $100,000 in SBC Communications stock, up to $50,000 in Wal-Mart stock and up to $15,000 in Pfizer stock, among others, while he presided over lawsuits involving the companies or their subsidiaries. In fact, it appears that since he was appointed by Bush in 2001 as a federal district judge in Oklahoma, Payne has been sitting inappropriately on at least one case at any given moment for nearly his entire federal judgeship.

Last fall, Payne's nomination to the 10th Circuit got little public attention while the media focused on the president's Supreme Court nominations. But Chief Justice John Roberts and current nominee Samuel Alito have tripped over the conflict of interest issue as well. Roberts, who holds an array of blue chip stocks and has unprecedented corporate ties for a sitting Supreme Court justice, has already recused himself from numerous cases and admitted a mistake in not recusing himself earlier from another. Alito was grilled in Senate hearings this month about why in one instance he didn't follow through on a pledge to recuse himself from any case involving the mutual fund company Vanguard, in which he held investments.

Payne refused to answer repeated requests by Salon for comment regarding conflicts of interest in the cases over which he presided. When reached by phone for comment on Dec. 20, Payne said, "I do not have time ... I can't do it," before abruptly hanging up. He did not respond to a subsequent call, or to a follow-up letter delivered to his office on Dec. 22, detailing the problematic cases and asking for an explanation.

Praised for his integrity by a number of Oklahoma lawyers, Payne did eventually recuse himself in some cases and kept himself off others from the start. In the cases in which he didn't recuse himself, most of his actions were routine and procedural. Most of the cases were settled, rather than going to trial.

But informed of Payne's reported stock holdings, plaintiffs in some of the cases say that the judge may well have been swayed by those holdings. Whether he was or not, legal experts say he should have never presided over the lawsuits.

"If I was suing Wal-Mart and I knew the judge held stock in Wal-Mart, I'd be concerned about that," said professor Leslie W. Abramson, a legal ethics expert at the University of Louisville's law school, after reviewing Payne's cases. While there is no proof of malfeasance on Payne's part, Abramson says, the letter of the law is clear on judicial conflict of interest -- and Payne's conduct, he says, leaves the impression that Payne has run his court in a "sloppy" fashion. "He took an oath to follow the law. The judge is supposed to recognize these things himself. If he owned the stock, he shouldn't have been sitting on the case. That to me is a clear call," Abramson said. "I think it speaks to whether a judge has been doing his job responsibly and is likely to do his job responsibly in the future."

"There's no wriggle room here," says professor Stephen Gillers, a scholar of legal ethics at the New York University School of Law. "It's not just an ethics rule, it's a congressional statute -- a law." Even if he doesn't make any orders during the proceedings, he can't be the judge on such a case, Gillers says. "He's disqualified, period."

Linda Chambers, a resident of Muskogee, Okla., says she certainly wouldn't have wanted to go before a judge who owned stock in Pfizer when she sued the pharmaceutical giant for the death of her mother. Chambers' case was one of thousands of lawsuits provoked by the diabetes drug Rezulin, which was withdrawn from the market after being linked to liver damage and deaths. Chambers' mother, Margaret Owens, died at age 65 after liver and kidney failure while taking Rezulin. Chambers' case happened to go before Payne in 2002 and again in 2003, when he reported holdings of up to $15,000 in Pfizer stock. The lawsuit later moved to another court, bundled with similar suits, and was settled. Chambers' attorney, Tony Edwards, said Payne made no significant decisions in the case -- but Chambers said she would have asked for a different judge if she had known of his conflict of interest at the time.

"Sounds like the judge is deciding this case on his best interest also," said Chambers. "I wanted a judge that was impartial. That's what I thought the judges are supposed to be."

Payne's track record illuminates how conflict-ridden cases can slide through the cracks of a system that relies primarily on judges to regulate themselves. The financial disclosure forms that Payne signs and submits each year show a consistent core group of stocks year after year, including those in his most recent filing last September. Since 1999 (as far back as his filings are publicly available), court records show Payne participated in cases involving SBC, Tricon Global Restaurants, Pfizer, Williams Cos. and Wal-Mart while reporting stock holdings in those companies. Some of the lawsuits explicitly name the corporations, while others name subsidiaries, like Taco Bell and KFC (owned by Tricon) or Williams Oil Gathering (owned by the Williams natural-gas giant).

In the wake of the Watergate scandal, Congress passed a law in 1974 during an era of reform that made the rule for recusals unequivocal: Judges should monitor their finances and must disqualify themselves if they, their spouses or their children have a financial interest in the case -- "however small."

Enforcing the law is another matter.

Payne, for example, apparently broke the rules several times in 1999 as a magistrate judge -- yet the Senate confirmed Payne unanimously to become a district judge in 2001, without any mention of the issue.

Judges must fill out financial disclosure reports every year, identifying potential conflicts like stocks. But the filings are kept in an administrative office of the court system in Washington, and if anyone wants to see them, the judge is notified exactly who is asking. This requirement could intimidate lawyers who don't want a judge to find out they are snooping.

Tulsa lawyer Jeff Martin sued Tricon Global Restaurants on behalf of a former KFC restaurant manager who claimed he was owed disability benefits, a case that went before Payne in 2002. Martin says the judge didn't play a significant role in the case, which ended up being settled. But Martin had no idea that Payne's reported stock holdings included up to $50,000 in Tricon (now called Yum Brands). Martin says that if he had known, he would have informed his client -- but probably wouldn't have challenged the judge over it. "I'm not a greatly experienced, big-time lawyer where I think I can push judges around," he said. "I probably would have left it at [Payne's] discretion."

In December 2005 the American Bar Association gave Payne a unanimous "well qualified" rating, its highest mark. The ABA rating committee evaluates a nominee's integrity and reputation, but its guidelines don't say whether it reviews a judge's cases for conflicts of interest. The committee chair declined to comment further.

Payne's Senate confirmation hearing has not yet been scheduled. He currently presides as chief of the U.S. District Court in Muskogee, Okla.; if confirmed to the 10th Circuit, Payne would serve on the court of last resort (except for those relatively few cases that make it to the Supreme Court) in a region covering Colorado, Kansas, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Utah and Wyoming.

Senate Judiciary Committee staffers perform a thorough screening of judicial nominees, but don't always review every case a nominee ever sat on, according to Tracy Schmaler, a spokesperson for the ranking committee Democrat, Sen. Patrick Leahy. Finding possible conflicts among hundreds of lawsuits can require a lengthy, exhaustive comparison of a judge's financial interests to all of his cases.

Most district courts now have computer programs that can monitor a judge's caseload for conflicts. But it's up to the judge whether to plug in financial information and use the system. A few federal courts have pioneered reforms: The Northern District of Iowa went so far as to disclose judges' financial interests on the Internet and to require parties in a lawsuit to file a list of all related financial interests. The clerk's office then looks over a judge's cases, and if it identifies a conflict, it automatically reassigns the case before the judge even sees it.

But neither of the clerk's offices in the Northern or Eastern District of Oklahoma, where Payne presides, gets involved with monitoring a judge's conflicts.

University of Louisville's Abramson argues that all judges should be required to use the computer system, and that every clerk of the court should reassign cases with conflicts before they reach the judge's chambers. "The integrity of the process is on the line," he said, pointing out a "systemic failure" that goes beyond Payne. "The U.S. Supreme Court has said that the appearance of impartiality is as important as the fact itself of impartiality."

And yet, in Oklahoma, some lawyers don't see it that way.

Harold Witcher, now retired from practice, helped bring a case against Southwestern Bell Telephone, among others, while Payne reported stock holdings in parent company SBC (now renamed AT&T). Payne issued a couple dozen orders over five months before recusing himself in March 2002. Moreover, Southwestern Bell and other defendants were represented by fellow members of Payne's church, where Payne sits on the board.

Though federal statute requires a judge to recuse himself when "his impartiality might reasonably be questioned," the circumstances surrounding Payne in that case didn't trouble Witcher. "That Judge Payne, I tell you -- he calls it like he sees it. He doesn't care who's sitting where."

One of Witcher's clients, however, said she didn't think Payne should have presided.

"If he is invested in SBC, he's going to rule in favor of SBC and not the ordinary people," said Kathy Lamon, 52, who sued the company and others because of high phone bills charged to families of prison inmates. "I would think it would be a conflict of his interest to be seated on a case like that."

Witcher said he vaguely remembered that Payne mentioned the stock conflict -- and then proceeded with the case because the attorneys didn't object. Oklahoma City lawyer Carrie Hoisington, who was involved in a separate case over which Payne presided, recounted a similar scenario in which Payne may have raised the issue and the case proceeded nonetheless.

Professor Steven Lubet, a legal ethics authority at the Northwestern University School of Law, argues that Payne is guilty only of careless mistakes that are not particularly meaningful "in terms of assessing someone's career or someone's integrity."

Other experts say Payne is clearly in the wrong, regardless of intention. "It doesn't matter whether his rulings were mundane or major, and it doesn't matter that the attorneys agree -- this is a conflict that's not waiveable," said Gillers of NYU. "Maybe the judge just didn't realize that. But he's the judge -- he should read the statutes."

The law does not include a specific penalty for violations, but judges can be censured by a committee of colleagues or, in extreme circumstances, impeached and removed from the judiciary by Congress.

Curiously, Payne recused himself from many cases that intersected with his reported stock holdings, only to later sit on cases concerning the same companies. In March 2002, for example, he suddenly jumped off several lawsuits involving SBC and its subsidiaries after issuing numerous orders. Court records show he cited his SBC stock ownership as the reason in one case; the suit against Cingular Wireless also named SBC, which owns roughly 60 percent of Cingular. But in 2004, Payne presided over another case against Cingular -- and received yet another Cingular case last spring. After being contacted for this story, and without the prompting of attorneys working on the case, Payne recused himself Jan. 3.

"I have absolute complete faith in him as a judge," said David Blades, an attorney who brought the recent case against Cingular. "If he had come and said to me, 'I own stock in Cingular,' I would say, 'So what?'"

But Abramson warns against participating in even the most routine procedures, because it's impossible to predict the twists and turns of a case. In Payne's situation, the various settlement conferences over which he presided could've been particularly problematic: Judges can act as "some of the greatest arm-twisters in the world" in these conferences, Abramson said, actively pushing for resolution of the case rather than having it go to trial.

As a nominee for the federal bench in both 2001 and 2005, Payne did in fact pledge to the U.S. Senate to adhere to conflict-of-interest rules. "In general, I plan to comply with Canon 3 Code of Judicial Conduct and the provisions of 28 U.S.C. 455 concerning disqualification of United States District Judge or United States Magistrate Judge," he wrote in a 2001 questionnaire.

But apparently his willingness to follow through on recusing himself was a different matter. "If it happened routinely," said Gillers of NYU, "then that shows a lack of awareness of his professional responsibilities that I think warrants an explanation."

Shares