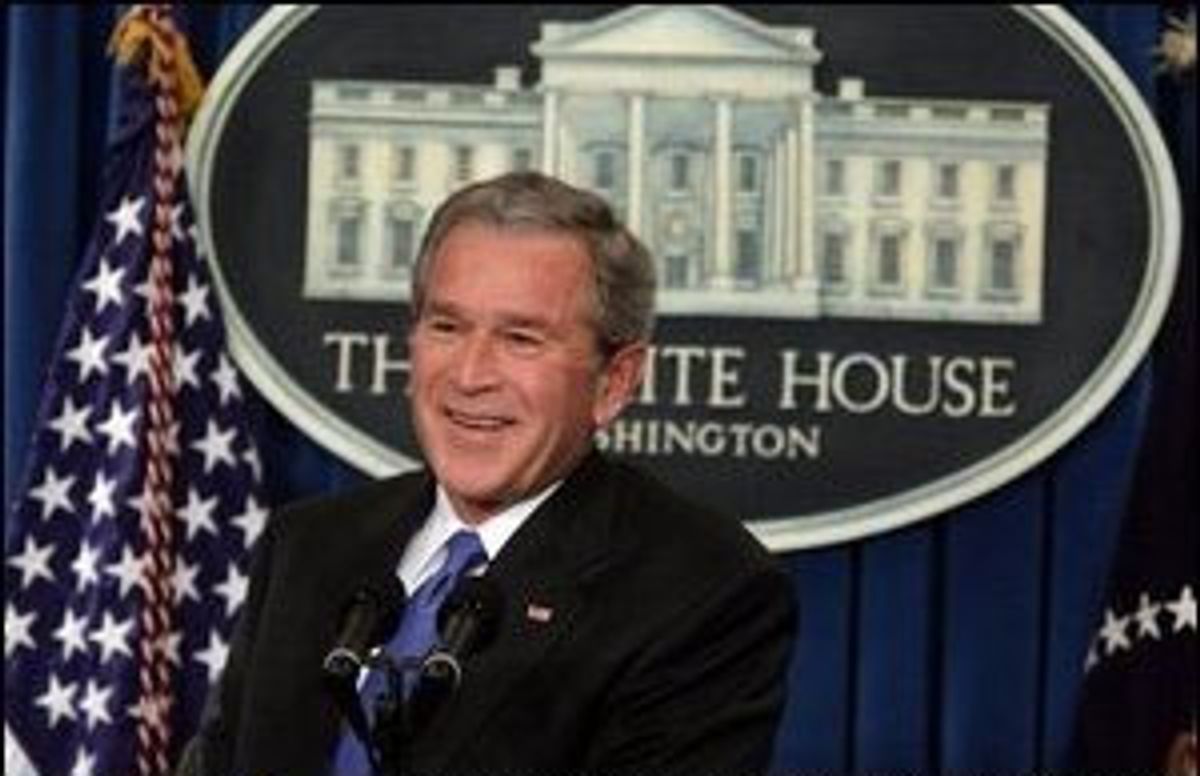

Sticking to his script and determined to deceive, George W. Bush brushed aside questions about Jack Abramoff at Thursday's press conference with a weak joke.

Reaffirming White House press secretary Scott McClellan's decision to withhold official photographs that show the president with the crooked super-lobbyist, Bush quipped, "You're asking about pictures -- I had my picture taken with him, evidently. I've had my picture taken with a lot of people. Having my picture taken with someone doesn't mean that I'm a friend with them or know them very well. I've had my picture taken with you [laughter] -- at holiday parties."

Heh-heh, as Jon Stewart would say. Bush enjoys making a funny, but he sounded much like his stolid press secretary while repeating those bland, unresponsive talking points about the Justice Department's "serious investigation" of lobbying on Capitol Hill and refusing to acknowledge questions that went beyond the admittedly embarrassing pictures. Asked about Abramoff's access to officials in the White House, which McClellan has refused to discuss in detail, Bush again brought up the pictures and added, "I never sat down with the guy."

But what he and McClellan still won't answer is how many times Abramoff came into the White House, which senior staffers met with him and what they discussed on those occasions. It is bizarre to pretend, as McClellan does almost every day, that this information has no relevance to the story of Abramoff's influence peddling -- or that the public has no right to know whether and how Bush aides were involved. "I'm not aware of anything that has anything to do with the investigation," he said, with a straight face.

The president's own amusement about this entire matter is understandable. Unlike his predecessor, whose every sentence was subjected to skeptical parsing by the Washington press corps, this president can utter the most implausible statements without fear of contradiction by his credulous chroniclers. Why should he worry about this scandal, which already has reached deeply into his administration as well as Congress, when he can pretend that he doesn't "know the guy"?

Bush suggested today that he had scarcely heard of the lobbyist until his indictment, doesn't remember ever meeting him and knows little about him, but there are more than a few reasons to wonder how that could possibly be true:

Abramoff has worked closely for decades with Karl Rove, his old friend and Bush's top political advisor, as well as with Grover Norquist, Ralph Reed and members of the Bush campaign's inner circle. Bush performed favors for the lobbyist as early as 1997, when he wrote a letter about school choice to Abramoff's clients in the slave labor haven of the Mariana Islands. (The letter was copied to an Abramoff associate.)

Abramoff sent his personal assistant, Susan Ralston, to serve as Rove's personal assistant during the earliest weeks of Bush's first term. Within a few months, he had arranged a May 2001 meeting with the president for two tribal leaders he represented.

Abramoff's partner David Safavian was appointed by Bush to serve as the top procurement official in his administration (and last year pleaded guilty to five felony counts that stemmed from an Abramoff scheme to acquire control of Washington property owned by the government).

Abramoff served on the Interior Department's transition team -- where he was exquisitely positioned to advance the interests of his clients in the Mariana Islands and on Indian reservations -- and subsequently raised more than $100,000 for Bush's campaign. The lobbyist and his aides met with or contacted administration officials on at least 195 occasions to promote client interests during the first several months of Bush's first term, according to Abramoff's billing records.

And then there is the most intriguing instance of a presidential action that, wittingly or not, served Abramoff's interests. On Nov. 18, 2002, the federal prosecutor in Guam issued a subpoena to court officials on the Pacific island, who had secretly retained the lobbyist to stop legislation in Congress that would have curtailed their authority. The subpoena demanded all the records concerning the strange Abramoff contract from the administrative director of the Guam Superior Court.

On the day after U.S. attorney Frederick Black issued the subpoena to Abramoff's covert clients in Guam, the White House announced the president's decision to replace him. A career federal prosecutor who had held the Pacific island post for a decade, Black was demoted to a staff position. His replacement was a lawyer recommended by the Republican Party on Guam. Rove received the recommendation from another lobbyist for government officials Black had been investigating.

And of course, Bush's firing of Black killed the investigation of Abramoff's secret dealings with the Guam court officials, as the Los Angeles Times reported last August.

Perhaps the president really doesn't know Abramoff and had no idea that the lobbyist was telling clients that he could fix the Bush White House. Maybe his abrupt removal of the U.S. attorney who was investigating Abramoff three years ago was merely a curious coincidence. But if he has nothing to hide, then why are he and his press secretary concealing the facts and photos of Abramoff's repeated visits to the White House?

Shares