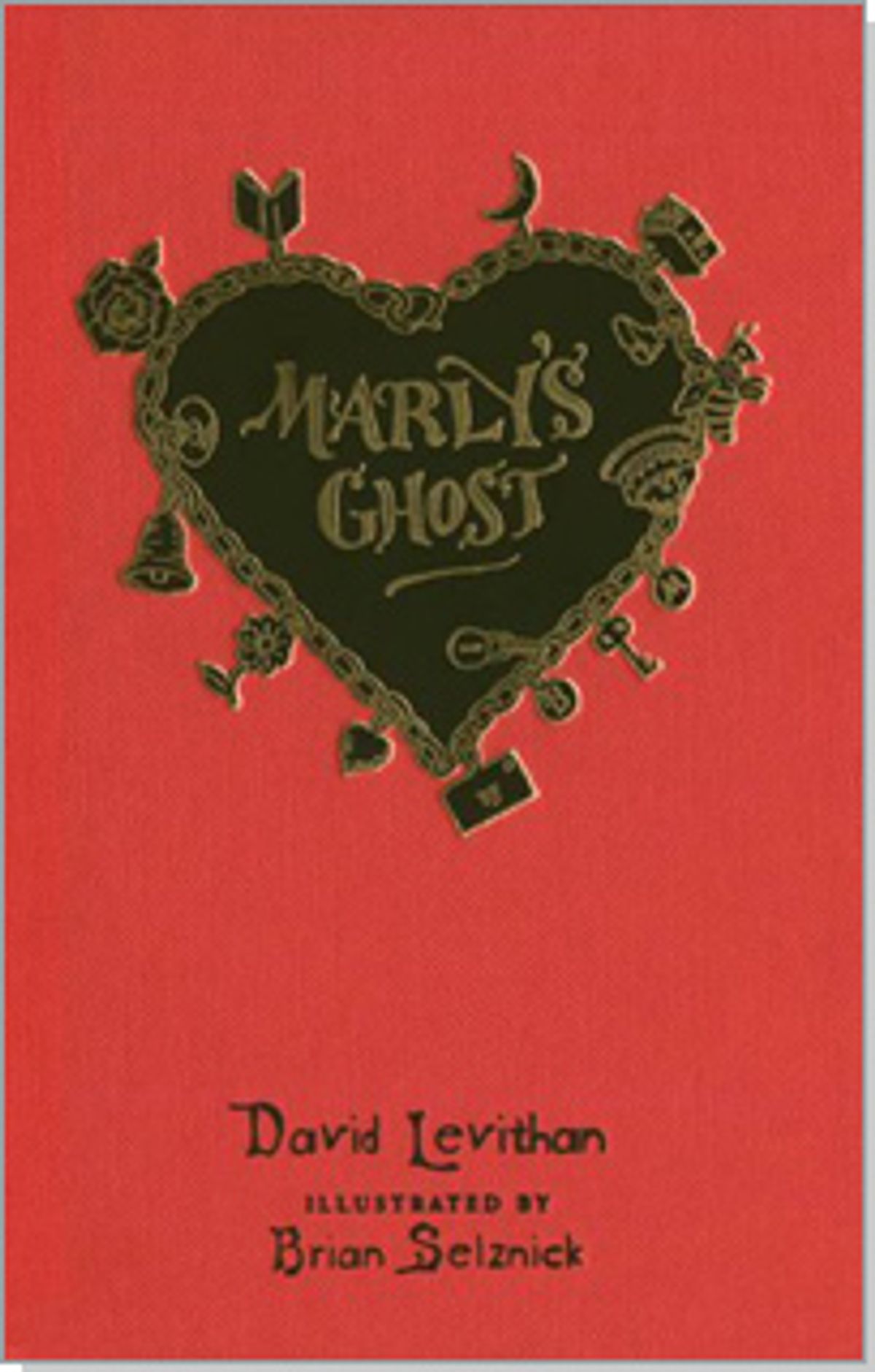

In the simple pen-and-ink illustration adorning the cover of "Marly's Ghost" -- a slim new novel by acclaimed young adult author David Levithan -- a girl's charm bracelet lies curled in the shape of a heart, stark against a magenta background. Dangling from the links is an assortment of childish talismans: a sliver-shaped moon, a bumblebee in flight, an unopened letter, a key, a book, a rose. It is an iconic image that illustrator Brian Selznick renders in fine lines and a monochromatic palette, with an assured combination of delicacy and gravitas that suggests to the reader -- before even cracking the book's spine -- that the love story inside, like the bracelet itself, will have both sweetness and sharp edges.

As the title cleverly hints, "Marly's Ghost" is a modern-day retelling of the Dickens classic "A Christmas Carol," with the seasonal setting of Christmas swapped for Valentine's Day. While adults will recognize the plot, Levithan's version, an adolescent romance, is aimed squarely at teen readers -- albeit ones who might favor vintage clothes and black nail polish. In fact, if your son or daughter has outgrown Cupid-shaped cookies, but is still in want of a Valentine's treat, this may be one gift you can agree on.

In this version, Ebenezer Scrooge becomes "Ben," a forlorn 16-year-old recovering from the untimely death of his high school sweetheart, Marly. Plagued by memories of her decline into cancer and made cynical by his loss, Ben anticipates the approaching holiday with a humbug in his heart and lashes out at friends who dare console him. Indeed, from the novel's opening line, it's clear this is one Valentine's story that will contain few candy hearts and construction-paper cards. Levithan starts out furiously, echoing the Dickens original: "Marly was dead, to begin with. There was no doubt whatsoever about that. I had been there. When she went off the treatments, she decided she wanted to die at home, and she wanted to be there with her family. So I sat, and I waited, and I was destroyed."

With impressive bravura, Levithan draws liberally upon Dickens' tale, crafting a pastiche that's one part teenage fantasy and one part fairy tale. This time, the chain that Marly's ghost drags is not a leaden anklet of gold coins and safe boxes, but a larger-than-life replica of the bracelet from the book's cover -- weighted down by "books ... flowers from holidays, and blankets shared after sex" -- the physical symbols of experiences Marly shared with Ben in life and of the memories that tie her to him in death. Marly comes to haunt a suicidal Ben on Valentine's eve -- her body transparent and still frail but with a "baby-chick" fuzz of hair growing back -- to warn that he will soon be visited by three spirits, sent to reveal the true nature of love. They alone, she explains, may offer Ben salvation from his own lonely death.

Readers familiar with the original tale may have a hunch what lies ahead, but will be pleasantly surprised by Levithan's creative flourishes -- like a Ghost of Love Past who spirits Ben back to Marly's first day of school, where he watches her "teeter from foot to foot, in a dress that was slightly too new, slightly too nice." At an "anti-valentines day party," guests nibble homemade candy hearts, whose original messages have been scratched out and replaced with the words "despair," "heartache" and "love sux." And in Levithan's imagination, Fezziwig becomes a merry-making upperclassman who, decked out in a waistcoat and a Cupid-print tie, throws the magnificent ball at which Marly and Ben share their first awkward dance. Although Selznick's moody illustrations of ghostly figures and barren trees appear sparingly throughout, they provide a quiet counterpoint to Levithan's at times wrenching prose.

Indeed, one may find Levithan's approach either moving or maudlin. In the book's best moments, his language is plainly piercing; as Ben wanders the empty halls of high school, Levithan writes, "Black hearts -- I wanted to see black hearts in the halls, hearts that smelled like smoke and weighed as much as sadness ... The last bell of the day had just rung, but it was quite dark already, with a fog covering the parking lot and the football field and the field beyond. I wanted to be out there, evaporating." But there are other scenes that fall flat, where Levithan overindulges the melodrama and veers perilously close to the kind of self-consciously precocious dialogue that smacks of early episodes of "Dawson's Creek." For example, while tangling with his friend Fred -- in the updated version a stand-in for Ebenezer's sympathetic nephew -- an indignant Ben exclaims, "I am sick and tired of all this useless energy spent on love ... I am sick of glorifying the vulnerability and codependency of dimwitted lonely people who spend thirty dollars on a dozen roses and think that means something more than a waste of money!" Finally, Levithan -- whose previous book, "Boy Meets Boy," was a wholly disarming and original homosexual teen romance -- here makes occasional missteps in his dedication to envelope-pushing inclusiveness. It's hard to imagine how the decision to split Tiny Tim into two separate characters -- a naive, gay freshman couple named, improbably, Tiny and Tim -- could ever have seemed like a good idea.

But Levithan is lucky in that, like Ben's devotion to Marly, by the end of the story the strength of his writing and the honesty of his emotion obliterates many of the obstacles in his path. Ben concludes his ghostly journey a transformed man -- wizened by the visions of his happy past and solitary future, and shocked straight out of his adolescent ennui -- realizing (as we all must eventually) that his first love, while precious, was only the beginning of a multitude of great romances. Like a handmade card passed between lovers, "Marly's Ghost" leaves readers feeling that an intimate secret has been shared -- and closes with a Valentine's message, as fitting in Dickens' day as now: Love "is all such a blessing, in the beginning, and the end, and the during."

Shares