Count me among those who turned up their noses at Sarah Dunant's bestselling "The Birth of Venus," figuring it to be one of those sentimental historical novels pegged to a famous painting and using the past purely as an opportunity to dress up a cheesy love story in velvet and corsets. The book even had a heroine who aspired to be a painter in 15th century Florence, just the kind of plucky role-model girl you find in an animated Disney feature. Why bother to give your novel a historical setting if you can't be bothered to be true to it? That's become my much-repeated gripe.

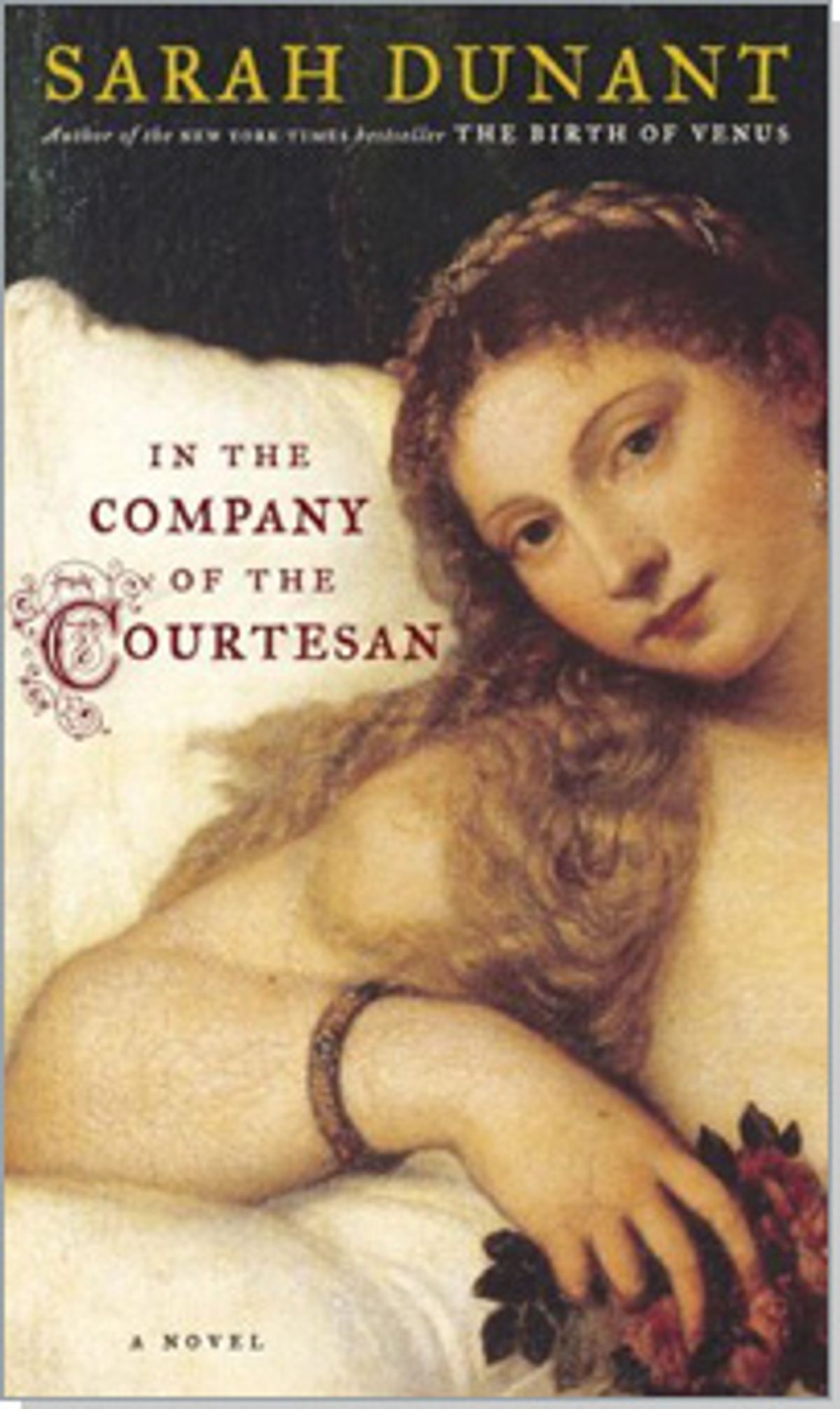

I'll have to retract my sneers, though, if "The Birth of Venus" is as enjoyable as Dunant's new novel, "In the Company of the Courtesan." It's hard, though, to see how the first book's young heroine could compete with the witty, bawdy, illusion-free narrator of "Courtesan," the dwarf Bucino Teodoldo. Bucino works for one of the most celebrated courtesans in 16th century Rome, Fiammetta Bianchini; to the world, he's a kind of novelty servant or pet, whose ugliness serves to make her appear more beautiful. Behind closed doors they are comrades and business partners bound together by an unshakable loyalty rooted in their hardscrabble pasts, their cleverness and their will to thrive. "It is a marvel to me still," Bucino says of Fiammetta, "how even when the world is crumbling about her the kind of challenges that would have most people pissing in fear only seem to make her more relaxed, more vibrant."

The novel begins with the sack of Rome in 1527 by the army of the Holy Roman Emperor, in league with Spanish and German Protestant troops. Bucino and Fiammetta barely escape with their lives, and a gang of fanatical Protestants has violently shorn the courtesan of her key asset, her cascade of golden hair. "Like good Christians," Bucino explains, "our riches were all on the inside" -- meaning the two companions have swallowed a choice selection of Fiammetta's jewels in order to smuggle them out of the city. She teases him for choking down the smaller rocks, then adds, "I want no Bucino-style jokes on how well trained I am in such things."

The pair wash up in Venice -- Fiammetta's hometown -- and begin the slow, tricky process of setting up business again. This provides Bucino with ample opportunity to indulge his finely honed and irresistible cynicism. "Impotence often makes grumblers of old men," he observes when an acquaintance bemoans the passing of the good ol' days, "for as death gets closer it is more comforting to imagine that they are leaving hell for heaven rather than the other way around." Fiammetta tells Bucino, "you live with your eyes too close to the ground," but the bracing earthiness of his perspective is exactly what lifts this book above the average run of "lush," idealized historical novels.

Fiammetta and Bucino are surrounded by vindictive neighbors and treacherous servants and friends, so when Fiammetta allows La Draga, the local apothecary -- a blind, lame woman she has known since her girlhood -- into her confidence, Bucino is both suspicious and a bit jealous. Still, they flourish, checking out the competition at the place where the best Venetian courtesans display their wares (in church), and building a prestigious clientele. They include a Venetian nobleman whom Fiammetta prefers to entertain in company: "That way he can bore other people and I can be sure to stay awake until I have to go to bed with him. You have no idea, Bucino, how tedious power can make men."

Some tedious things you might expect from such a story are blessedly absent from "In the Company of the Courtesan." There are no paeans to the watery beauty of Venice, a theme that was exhausted back in Henry James' day. "My God, this city stinks," is the first thing Bucino has to say about it, and he doesn't find much cause to soften his opinion later. Dunant doesn't make a fetish out of romantic love either, always a temptation when one of your main characters is a prostitute. Fiammetta does return the passion of a young Venetian (derisively referred to as "the pup" by Bucino). But the author never presents this as her one chance for "true happiness," as a more conventional storyteller would be tempted to do. In fact, at any point in "Courtesan" when you think you know where the story's going, Dunant takes a sharp left turn and heads for parts unknown without ever resorting to implausibility or wishful thinking. (This is not a story for those who like unqualified happy endings.)

"Courtesan" finally emerges as something very rare, a celebration of the complicated and undersung affections that flourish between colleagues and friends. Through Bucino, the novel aligns itself not with glamorous aristocrats and virtuous maidens, but with everyone who pulls his or her own weight in a world that's very seldom romantic or sentimental. Revising his view of La Draga, Bucino thinks of his lady, their Jewish pawnbroker and the blind potion-maker as possessing their own kind of nobility, despite their dubious status in Venetian society. "We are working men and women, all of us," he decides, "despite the burdens of our race or our deformities we have found ways to be in the world, dependent on no one, earning our living with a kind of pride."

Shares