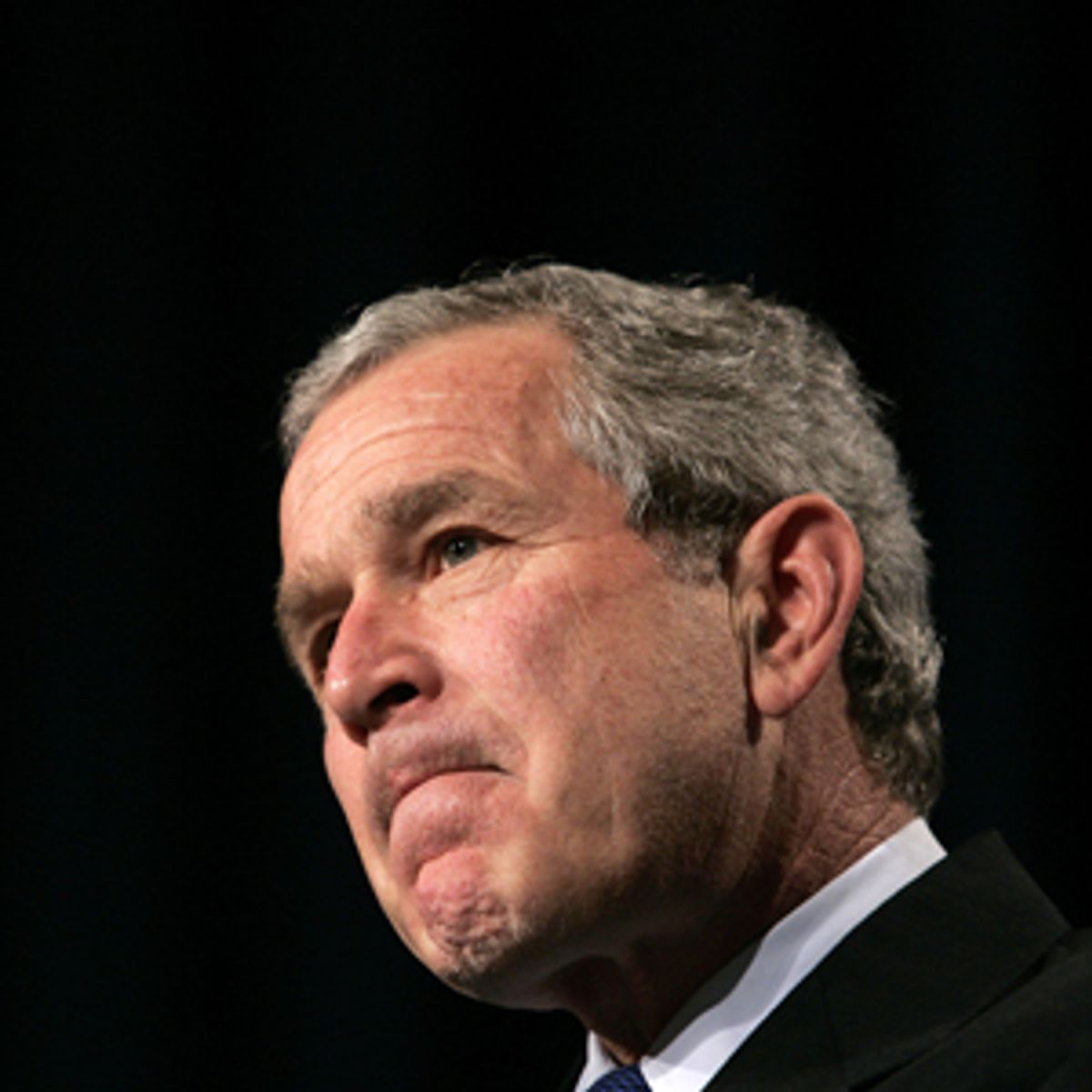

On his latest public relations offensive, President Bush went to Cleveland Monday to answer the paramount question he said people have on their minds about the Iraq war: "They wonder what I see that they don't." After mentioning "terror" 54 times and "victory" five, dismissing "civil war" twice, and asserting that he is "optimistic," he called upon a citizen in the audience, who homed in on the invisible meaning of recent events in the light of two books, the Book of Revelation and "American Theocracy" by Kevin Phillips. Phillips, the questioner explained, "makes the point that members of your administration have reached out to prophetic Christians who see the war in Iraq and the rise of terrorism as signs of the Apocalypse. Do you believe this, that the war in Iraq and the rise of terrorism are signs of the Apocalypse? And if not, why not?"

Bush's immediate response, as transcribed by CNN, was, "Hmmm." Then he said, "The answer is I haven't really thought of it that way. Here's how I think of it. First, I've heard of that, by the way." The official White House Web site transcript alters the punctuation, dropping the strategic comma, adding "the" and thereby changing the meaning: "The first I've heard of that, by the way."

But it is certainly not the first time that Bush has heard of the apocalyptic preoccupation of much of the religious right, having begun his alliance as his father's liaison to its leaders in the 1988 presidential campaign. Jerry Falwell told Newsweek two years ago that he brought Tim LaHaye, then an influential right-wing leader and the author of the Left Behind series, to meet Bush at the time: "I'm pretty sure I introduced Tim to George W." LaHaye's Left Behind novels, dramatizing the rapture, battle of Armageddon and Second Coming, and ending with the vanquishing of the secular antichrist, have sold tens of millions of copies.

But it is almost certain that his Cleveland Q&A was the first time Bush had heard of Phillips' new book. Phillips was the visionary strategist for the presidential campaign of Richard Nixon in 1968, foreseeing in its lineaments the making of political realignment. His 1969 book, "The Emerging Republican Majority," spelled out the shift of national power from the Northeast to the South and Southwest, which he was early to call the "Sun Belt." He grasped that the Southern Democrats in reaction to the civil rights revolution would become Southern Republicans. He also had a sensitive understanding of the resentments of urban ethnic Catholics against blacks on issues like crime, school integration and jobs. But he never imagined that evangelical religion would compound and transcend these animosities to transmute the coalition he helped fashion into something radically new that now horrifies him.

In "American Theocracy" Phillips describes Bush as the founder of "the first American religious party," in a country that has "never had a national religious party of any kind." The terrorist attacks of Sept. 11 gave Bush the pretext for "seizing the fundamentalist moment." Rather than forging a new realignment, Bush won narrow victories by manipulation of a "critical religious geography" and hyping of issues such as gay marriage. This was a politics beyond mere resentment. Phillips writes, "New forces were being interwoven. These included the institutional rise of the religious right, the intensifying biblical focus on the Middle East, and the deepening of insistence on church-government collaboration within the GOP electorate." The rise of the religious right, according to Phillips, portends a potential "American disenlightenment," already apparent in Bush's hostility to science.

Even Bush's failures have become pretexts for advancing his transformation of the American government. On March 7, for example, he issued Executive Order 13397, establishing a Center for Faith-Based and Community Initiatives at the Department of Homeland Security. He has already created such centers in other federal departments. Exploiting his own disastrous emergency management in the wake of Hurricane Katrina, Bush is funneling funds to churches on the Gulf Coast as though they can compensate for governmental breakdown. Last year, the White House deputy director for faith-based initiatives, David Kuo, resigned with a statement that "Republicans were indifferent to the poor" and that the White House had "minimal commitment" to "compassionate conservatism."

As Bush's melding of church and state accelerates, the faith-based turns into the reality-based. The theocratic impulse has always been about earthly power and has provoked intense and unexpected opposition. Within hours of its publication, "American Theocracy" skyrocketed to the No. 1 bestseller on Amazon. At the movie theaters, "V for Vendetta" -- a dystopian thriller in which an imaginary Britain is a metaphor for Bush's America, ruled by a totalitarian, faith-based regime, where gays are rounded up and the hero is a Guy Fawkes-like terrorist who blows up the Parliament -- is a surprise No. 1 box office hit. Bush has succeeded in getting American audiences to cheer for terrorism.

Shares