At their best, the songs of self-made pop phenomenon Daniel Johnston are distillations of everything we love about pop music, folk-art fantasias in which out-of-control motorcycles serve as metaphors for the heart's unpredictability and navigating love's confusion is likened to walking a cow on a leash. Johnston is a reclusive, astonishingly prolific singer-songwriter and visual artist who insinuated himself into the Austin, Texas, pop-music scene in the early '80s and went on to become a cult figure among musicians and pop-music fans through the dozens of homemade cassette tapes he recorded, and tirelessly distributed, over the next decade or so. The tapes' titles range from the piercingly direct ("Songs of Pain") to the disarmingly cheerful ("Hi, How Are You"); their covers are adorned with whimsical line drawings of strutting naked baby-men, or Martian frog creatures with quizzical round eyeballs perched on the ends of long antennae.

The tapes look and sound deceptively unsophisticated: Johnston has the kind of voice that drives some people crazy, a passionate parakeet's warble that wavers in and out of tune according to its own weird harmonic logic. But the songs themselves, which have been championed (and sometimes covered) by the likes of Sonic Youth, Yo La Tengo and Kurt Cobain, are sometimes difficult to listen to for another reason: They're so nervously alive that it's hard to distance yourself from the fragile soul who wrote them. Johnston's pulse beats so close to the surface that its thrumming is sometimes difficult to bear.

That's the quality Jeff Feuerzeig seeks to capture -- and often does, very effectively -- in his sprawling, affectionate documentary "The Devil and Daniel Johnston." As its title suggests, the picture is something of a ballad, an ode to an elusive character who's both quintessentially human and so outlandish he almost seems unreal.

Johnston, now in his mid-40s, grew up in a family of Christian fundamentalists in New Cumberland, Va. He was a precocious teenager who spent much of his time drawing wild cartoons (disembodied, floating eyeballs have always been a favorite subject) and making clever little home movies with his older brother: In scratchy clips from these old Super 8's, we see Johnston playing dual roles, as himself and his mother, who, in her hair curlers and housecoat, harangues him mercilessly and feeds him a green Kool-Aid concoction for breakfast.

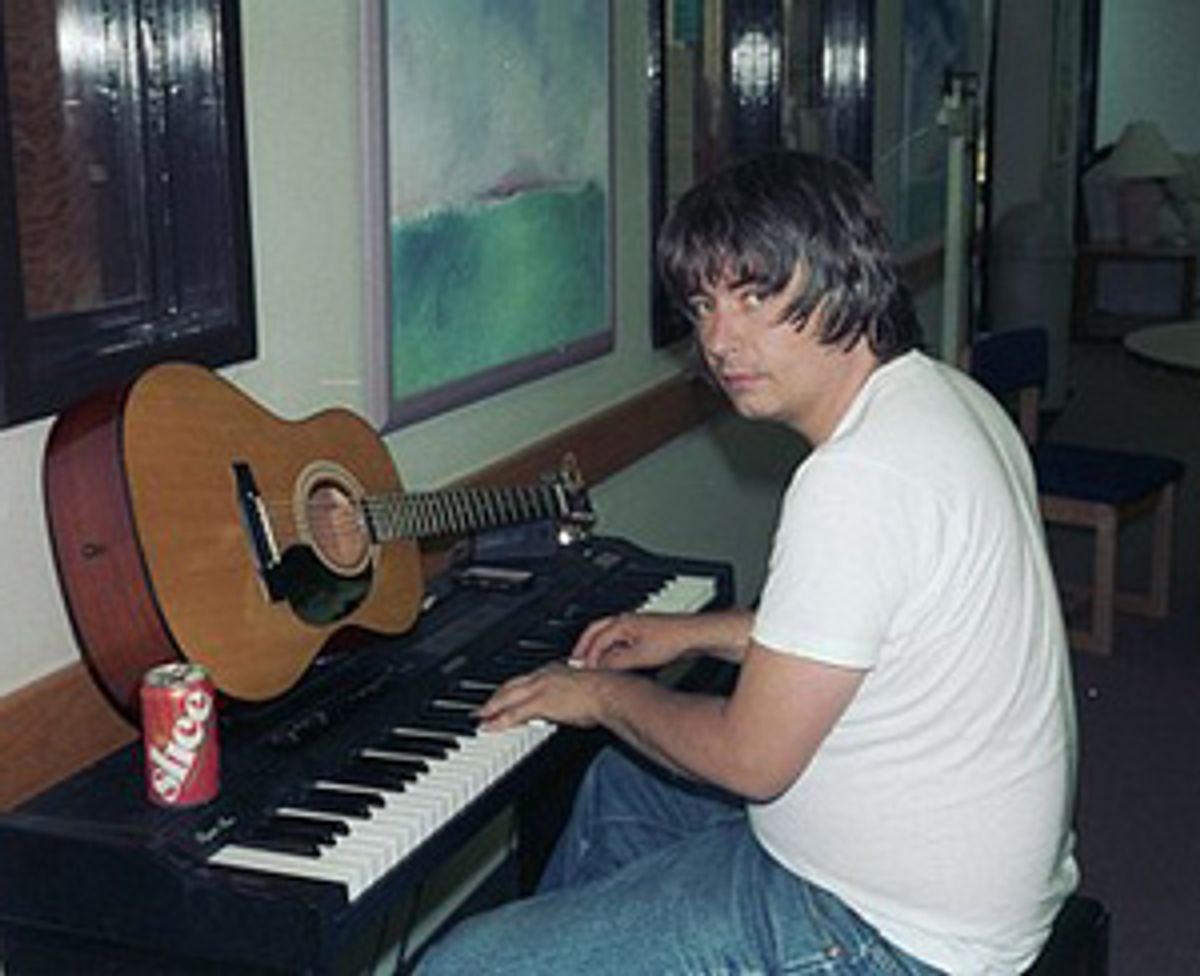

Johnston had a room in the family basement that he turned into a mini-archive of comic books, magazines and record albums, a kind of fallout shelter for a pop survivalist. (The room he lives in as an adult, in his parents' current home in Waller, Texas, is a re-creation of that earlier bunker.) As a teenager, Johnston recorded his thoughts and feelings onto cassette tapes; later, accompanying himself on rudimentary-sounding keyboards, he would turn those ruminations into painfully direct and heartfelt songs, which he would copy and distribute, with the zeal of a wheeler-dealer record exec, to friends and strangers alike.

Johnston was a smart, creative kid who somehow lost his footing on the way to adulthood. His mother, distressed by his wild drawings and even wilder imagination, tried to goad him into respectability, calling him "an unprofitable servant of the Lord." (Johnston's lifelong best friend, an articulate and astute artist and poet named David Thornberry, recalled that Johnston responded by calling himself "an unserviceable prophet of the Lord.") After high school, Johnston ran off and joined a carnival without telling his parents or siblings of his whereabouts. Forced to quit that gig -- apparently, he was beaten up by a carny thug for hogging a Porta-potty -- he found his way to Austin, where he landed a job cleaning tables at a McDonald's. There, he fell in with a group of local musicians, among them singer Kathy McCarty, who came to recognize the extraordinary but rather delicate nature of his talent.

After finagling a brief appearance on an early MTV show spotlighting the Austin music scene, in 1985, Johnston became something of a local celebrity; in the local music press, he topped several year-end polls in the songwriting category, beating out stalwarts like Butch Hancock. But Johnston was already starting to show signs of psychological instability in 1986, when he dropped acid, for the first time, at a Butthole Surfers show and flipped out. Not long after, he beat his then-manager over the head with a pipe; the guy survived, but Johnston was institutionalized for the first time.

Over the next 20 years, Johnston, diagnosed as manic-depressive, would spend time in and out of institutions. In that period he's hired and fired managers, signed a short-lived major-label record deal, and continued to make music: His favorite themes include the purity of true love and the omnipresent evil of Satan.

Feuerzeig, a longtime Johnston fan, walks a potentially tricky line in "The Devil and Daniel Johnston." There's no getting around the fact that a large part of Johnston's appeal is his fragility -- a fragility that may be endearing to us but is actually dangerous to him. "The Devil and Daniel Johnston" includes footage from the numerous performances Johnston has given over the years. In nearly all of these performances -- even his first, in Austin, where he took the stage before he barely knew how to play guitar -- his poise is eerily preternatural. Johnston's confidence shines through his jittery awkwardness: His voice may be quaking, but he looks out at the audience as if he were a conqueror -- as if the stage were the only place he could live the life he was destined to live.

But in some of these performances, Johnston's strained, rambling patter is distressing: We know we're watching a human being unraveling. Feuerzeig has to include footage like that if he's going to tell Johnston's story honestly, and he does so without being exploitive: You get the sense that he's always cutting away at just the right moment, erring on the side of showing us too little rather than too much.

It's a relief, too, that Feuerzeig doesn't do the easy Freudian cakewalk of blaming Bill and Mabel Johnston, Daniel's parents, for all, or any, of his problems. Feuerzeig devotes a great deal of time to Johnston's parents, who are now, even in their old age, Daniel's chief caretakers. Although they don't dwell on it, they clearly worry about what will happen to their son when they're gone, and their anxious sense of responsibility toward him is heartbreaking. And while Feuerzeig doesn't ignore their Christian fundamentalism, he doesn't use it as a scapegoat, either: He clearly has enough respect for the gravity of Johnston's emotional problems to know that they couldn't have been caused, or even necessarily aggravated, by Bible-thumping.

Still, there are places where Feuerzeig's technique is obtrusive when it should be translucent: Some sequences -- such as the one in which he interviews the Butthole Surfers' Gibby Haynes while the singer sits in the dentist's chair having a tooth filled -- feel gimmicky. And the picture includes a sequence depicting the way Thurston Moore and Lee Ranaldo, of Sonic Youth, once desperately drove through the streets of Hoboken, N.J., looking for Johnston, who was there to record an album with them and had gone AWOL. Against shots of nighttime city streets, we hear the voices of Moore and Ranaldo, saying things like, "Look -- there he is!" Moore and Ranaldo did tape themselves as they searched for Johnston, and you can hear their concern for their friend in their voices. But the sequence has the feel of a reenactment (it's not clear why anyone would tape such an event), and the movie includes no information to tell us that it's genuine.

But Feuerzeig's sympathy for his subject is never in doubt. He's concerned mostly with piecing together Johnston's story, talking extensively with the people who have been closest to him over the years, among them Thornberry and McCarty. Thornberry's comments are particularly touching, largely because he's not afraid to joke around and wisecrack: He talks about the day Johnston first appeared at his high school. He was "the new art guy -- the new art star," and Thornberry had to meet him. Without ever downplaying Johnston's problems, Thornberry never loses sight of the man as a human being. McCarty -- whose 1994 album "Dead Dog's Eyeball," a collection of Johnston covers, may be the best place for anyone who's curious about Johnston to start -- is similarly clear-eyed about her friend. We learn late in the picture that McCarty and Thornberry are married, a bittersweet footnote -- they're living the sort of life that Johnston can't, and yet without him, they never would have met.

And then there's the extensive footage, much of it vintage but some of it contemporary, of Johnston himself. The Johnston of the '80s is a wiry kid with a quavery, cartoon-character voice; he doesn't come off as particularly odd -- just maybe the sort of guy who's eaten far too much sugar-coated cereal in his lifetime. His eyes have a mischievous, distracted gleam. The older Johnston is far more low-key. And even though few of us can retain, after 40, the same kind of youthful energy we had at 20, Johnston looks as if too much of the life has been knocked out of him. He's bloated and heavy-set, possibly as much from medication as from that demon that chases all of us, middle age.

But when Johnston is onstage, he's as self-possessed as ever, temporarily becoming the person that fate -- or whatever it was that hit him -- prevented him from being. He may be a rock 'n' roll footnote in real life, but in his mind, he's a rock star. His imagination may be the cruelest gift God could have given him; then again, maybe it's actually the world's largest stage.

This story has been corrected since it was originally published.

Shares