By the time the Canadian cartoonist Hope Larson published her first graphic novel last year, she'd already been the toast of the independent comics underground for a while. Her early, handmade mini-comics staked out her conceptual territory: the world of dreams, where things are always becoming each other. (Some of them can be seen at her site.) "Salamander Dream," though, was the comics debut of the year. It's a simple fable for children about imaginary friends, nature and growing up, and its curving, mutable lines perpetually seem to be evoking three or four different images and ideas at once. There's a marvelous passage near its end that kids will read as two characters at play in the microscopic world of cellular biology; they won't notice the erotic undercurrents, but their parents will. (The entire book can be viewed for free at Secret Friend Society.)

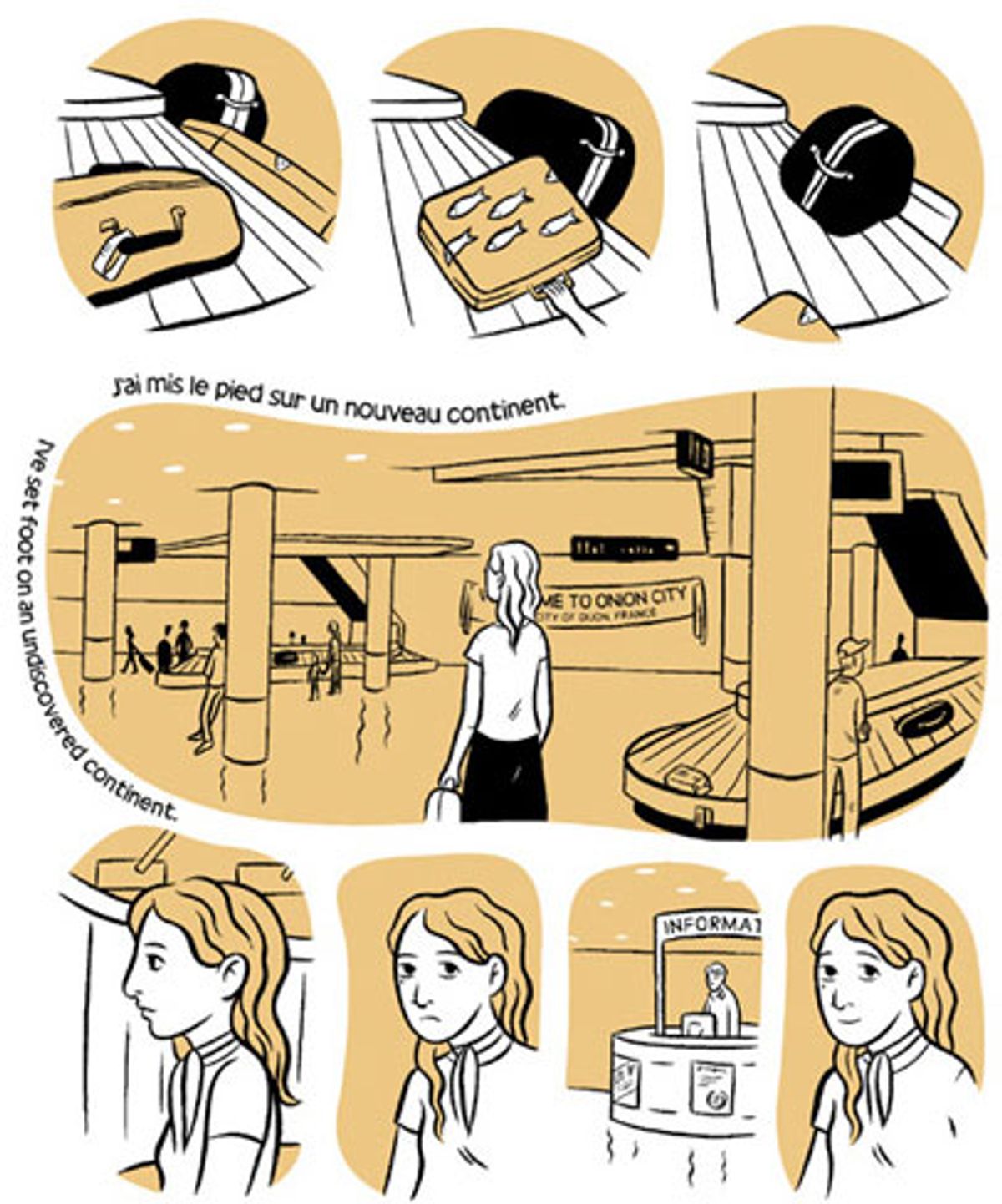

Larson's second mass-produced book, "Gray Horses," has just appeared, and as before, it's a very slight story whose depth comes from its exquisite visual design and imaginative resonance. Its protagonist is Noimie, an exchange student from Dijon, France, who's come to Onion City (a thinly disguised Chicago) to study art. She talks to herself, and thinks, in French, but every French sentence also appears in an English translation. Noimie has left a boyfriend behind, but she's mostly interested in exploring her confusing new environment, and taking as much delight in it as she can. She makes friends with a fellow student named Anna, carries on a nervous at-a-distance flirtation with a photographer, and gets flashes of homesickness. And, at night, she dreams about a little girl named Marcy, who rides a horse to the mountains to conceal a special photograph.

That's not much of a plot, but Larson isn't really interested in straightforward narrative; she's interested in investigating systems, and in coming up with novel ways to map them. (The book's endpapers, title page and acknowledgements page all involve fragments of maps, which is no accident.) Even the smallest processes are fair game for close consideration here. Instead of simply drawing a horse grazing in a field, Larson devotes a page to cartoony, cameo-shaped images of the horse leaning into the grass, taking a bite, chewing it a few times, swallowing and leaning back down. One lovely, relaxed scene diagrams, bit-by-bit, the mechanics of a lazy summer afternoon: a fan blowing, a half-eaten plate of cookies, someone stirring a pot of lemonade syrup, a girl lying on her friend's bed and doodling in a book. Mostly, though, what Larson's charting in "Gray Horses" is the overlapping categories of perception, documentation and imagination, and what art has to do with all three of them.

More than any other North American cartoonist of the moment, Larson focuses on her characters' sensory impressions, and not just visual imagery -- she loves sound effects (and integrates them into the lines and composition of her drawings), and even tries to give hints of scent and taste and texture. Anna introduces herself by noting that she lives in a bakery across the street from Noimie's apartment; her word balloon extends into an arrow, pointing to a little spot illustration of a building shaped like a loaf of bread, with smoke coming from its chimney (we understand from this that Noimie has a scent association with the bakery) and a young Anna standing in front of it. That image, in turn, has an arrow emerging from it that points to another word balloon: "I'm Anna." As the two girls shake hands, there's a "rumble" sound effect -- written in cursive, with the beginning of its "r" curved around into another arrow that indicates where the elevated train is coming from. And when the train arrives in the next panel, it appears as a stylized curve over Noimie's head, crossing the stem of her word balloon.

This sort of thing goes on throughout the book. Noimie's story is cute and charming if you zip through it, but it's much more fun to linger over every set of panels and let them provoke sense memories. One big theme of "Gray Horses," as with "Salamander Dream," is the flow of the world's images and sensations between the real and imaginary realms: Wrinkles in a blanket become a dream image of grass in a field, the moon half-concealed behind a cloud becomes a skipping stone in a hand. A breeze carrying the scent of flowers is represented as an array of wavy lines, a couple of which form the word "shhh" and a couple more of which go into Noimie's nose. When she dreams of a horse carrying a sick girl, coughing, through a fire, we see her hair as licks of flame and smoke; as she wakes up, the dream space evaporating behind her head is the negative image of the flames, and she's hearing somebody coughing in the next room.

The horse of Noimie's dreams is the book's central visual motif: It's echoed by the image of the horse on her room's wallpaper, a horse in a cave drawing from France, an invisible-ink blot of lemon juice on paper that Anna "develops" with a lighter, and shadows of leaves on Noimie's face in a Polaroid picture;6yy7 fragments of its shape are implied everywhere. This, Larson suggests, is how the imagination works: The artist's mind perceives patterns, and then extends them.

So it's curious that photographs and their fixed specificity are also so important in "Gray Horses." Photography is the medium that draws Noimie both to her dream's subject and to her nameless suitor, who takes pictures of her from a distance and leaves a few with her when she falls asleep in a park. ("Trust me, you don't want to date a photo kid," Anna tells her. "They have issues.") The way Larson uses photos for most of the story, they're safeguards for memory in a way that drawings aren't, but maps are; they preserve the physical world as it really is. The sick girl, Marcy, is on a mission to conceal a photograph of her siblings; her parents have burned the rest of her germy possessions (shades of "The Velveteen Rabbit"!), but that one piece of documentation means everything to her: "I don't want them to burn it! I don't care if I die!" And when Noimie falls asleep in her new apartment, she's got a photo of her back-home boyfriend propped up by her bedside; as she exhales, her breath takes on the form of that picture.

The only aspect of Noimie's artistic education we really see is the slides shown in her art history classes, which click past like the shutter of a camera. (By the end of the book, Noimie has become an avid photographer: "I want to remember everything here," she says.) In one scene, Noimie, falling asleep in her new apartment, hears a bell ringing outside her window, and wonders what it could be; the inset picture that explains the sound isn't just a drawing of a man pushing an ice cream cart -- it's a drawing of a Polaroid of a man pushing an ice cream cart, and the cart has a tiny word balloon with a single musical note coming out of it. You wouldn't see a word balloon on a real Polaroid, of course, but the point is that the photographed image is what's really happening.

Inescapably, though, the "Polaroid" is actually a hand-drawn, personal representation of a Polaroid. Given that "Gray Horses" is a book about the expression of creativity through mutable images, there's a lot more photography than drawing going on in it. But Larson's drawing could scarcely be less photorealistic: Her brush lines are bold and elegantly wavy, and she uses as few of them as she can get away with to imply everything from facial expressions to foliage. (When the book's bold style makes something in her drawings look ambiguous, she's got the endearing habit of slipping in explanatory labels with arrows: "bread crocodile," "watermelon-shaped cookies," "leak in ceiling.") Besides black and white, every page of the book uses a flat peach tone whose wobbly spread defines the borders of the panels Larson never outlines: The suggestion is that each drawing is a personal field of view, not a window into an objective reality.

The argument that photography documents and preserves the world and that drawing transforms it into something not quite true that belongs to the artist is slippery, though. Even within "Gray Horses," Larson doesn't quite make that claim explicitly, and she contradicts it by the end of the story. Marcy's photograph, an artifact of Noimie's dream world, slips into the reality of Onion City; Noimie finds a way to return it to the realm of the imaginary, and frees herself from her own history by sending a photographic relic of the past she's leaving behind into the world of dream horses, too. That doesn't make a lot of literal sense, but it's not supposed to. Dream logic is the only way to make a map of the processes of joy, and Larson is their ideal cartographer.

Shares