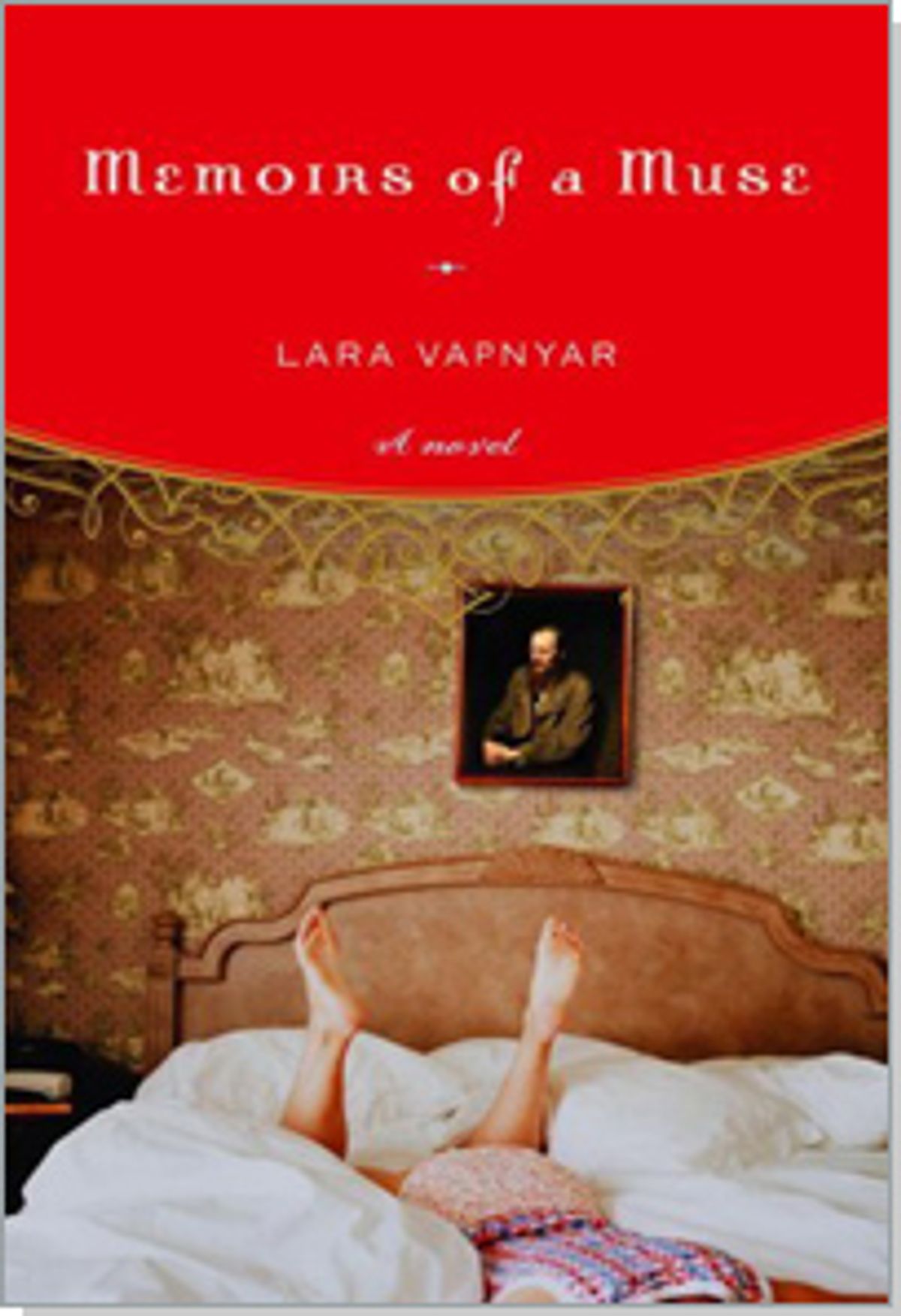

"Memoirs of a Muse," Lara Vapnyar's first novel (after the 2003 story collection "There Are Jews in My House"), is a little bit of many things: an immigrant novel, a literary satire, a bildungsroman. But most of all, it's a cautionary tale for that particular sort of young woman who yearns to attach herself to a man of genius. Vapnyar's narrator, Tanya, gets this notion into her head during her teenage years in Russia, and she tries to pattern her career as a muse after that of Apollinaria "Polina" Suslova, the mistress of Dostoevski. It almost goes without saying that both women end up disappointed with the muse's lot, but if Vapnyar goes on to say it anyway, she does so in an amusingly rueful way.

Tanya -- raised by a harried single mother and twice deserted by a father who left the family and then promptly died -- grows up feeling frustratingly unexceptional. She's neither especially pretty nor especially smart. She can do several things passably well. She longs to "become somebody accomplished, a luminary," but "that long-anticipated extraordinary talent still hadn't emerged. My many gifts rattled about like cheap jewelry in a sequined bag -- there wasn't a single gemstone." A lecherous schoolteacher insists that she is destined to become "the companion to a great man," and this, combined with the photographs of famous Russian writers her mother hangs on the walls of their Moscow apartment, persuades her that she is a born muse.

Tanya emigrates to New York in her 20s, and this naturally leads into some of the usual -- but not yet tiresome -- elements of post-Soviet immigrant fiction and memoir. There is the uncle who goes overboard on all the delicacies he couldn't get in the old country and battles for control of Society for the Former Doctors from Former Soviet Union. And there is the hard-bitten cousin in the too-short skirt and too-tight T-shirt with "Versace" emblazoned across the chest, dispensing advice about the dog-eat-dog nature of life in the States. "Though Americans were often criticized for having bad taste in clothes or ignorance of European culture," Tanya observes of her fellow expatriates, "they were clearly believed to be the superior race. 'I know this American ... ' or 'One American told me' people kept saying, unaware of how proud they sounded."

Finding little use for her training as a historian (her areas of interest include 19th century Russian makeup and what the ancient Romans ate for breakfast), Tanya gets a job at a dentist's office and goes for long walks in Central Park, in search for a great man to inspire. A random foray into a bookstore leads her to a reading by Mark Schneider, a middle-aged novelist at work on "a trilogy about a gifted but troubled Jewish boy growing up in a very ordinary, reasonably happy, moderately well-off New Jersey family." Romance, if you can call it that, ensues ("It's astonishing how little your presence bugs me," Mark tells Tanya), and she moves into his apartment on the Upper East Side.

The next section of the book is an enjoyable skewering of the typical self-regarding New York novelist of very modest talent and renown, as seen by his increasingly less awestruck young girlfriend. Mark shows little interest in Tanya herself (he even forgets that her father is dead) and reads nothing but biographies of famous writers, highlighting significant passages and writing "Mark" or "Mother" in the margins. He spends most of his time in the gym, visiting his shrink and his doctor, and shopping for vitamins and organic toiletries. "We shopped for shoes that you couldn't feel on your feet and for socks that made your feet warm but not sweaty," Tanya relates. "We kneaded, stroked, and rumpled a great variety of fabrics to pick out the shirt that would feel just right against Mark's skin."

Although Tanya at first thinks she's found a soulful alternative to the stagnation of Russia and her cousin's crass lumpen suburban materialism, it turns out the cousin is not entirely unfamiliar with men of Mark's ilk. "They won't miss their hour at the gym, or their testicular exam," she explains. "They go out of their way to prolong their sorry lives, at the same time fucking them up so badly that those lives become hardly worthy of prolonging ... What can I tell you Tanya?" she adds. "Hold onto your horse."

That warning comes a little late, but rest assured that Tanya does eventually regain control of her horse. And all along, she's reading the diaries of Suslova, the woman who haunted Dostoevski's greatest novels but who never got much out of the relationship herself. At the moment when Polina most expects to be exalted, after the consummation of their passion, Dostoevski turns to her and asks "Do you think Turgenev will agree to my offer?" Even when the genius is real, it seems, the preoccupations can be pretty mundane: "She had dreamed of having literary conversations with him, so that was probably it. They were having one right now."

"Memoirs of a Muse" ends with an O. Henry twist that's a little too tidy, but what the heck -- the impulse to ease the mordent, Slavic edge of Tanya's story is a sound one. Except for that final small gesture of New World optimism, this novel has the air of a weary, ironic shrug. "Whether she wanted it or not," Tanya observes about Suslova, "the fact remains: She became a muse. Yes, immortality doesn't do you any good. But how many people don't wish for it?"

Shares