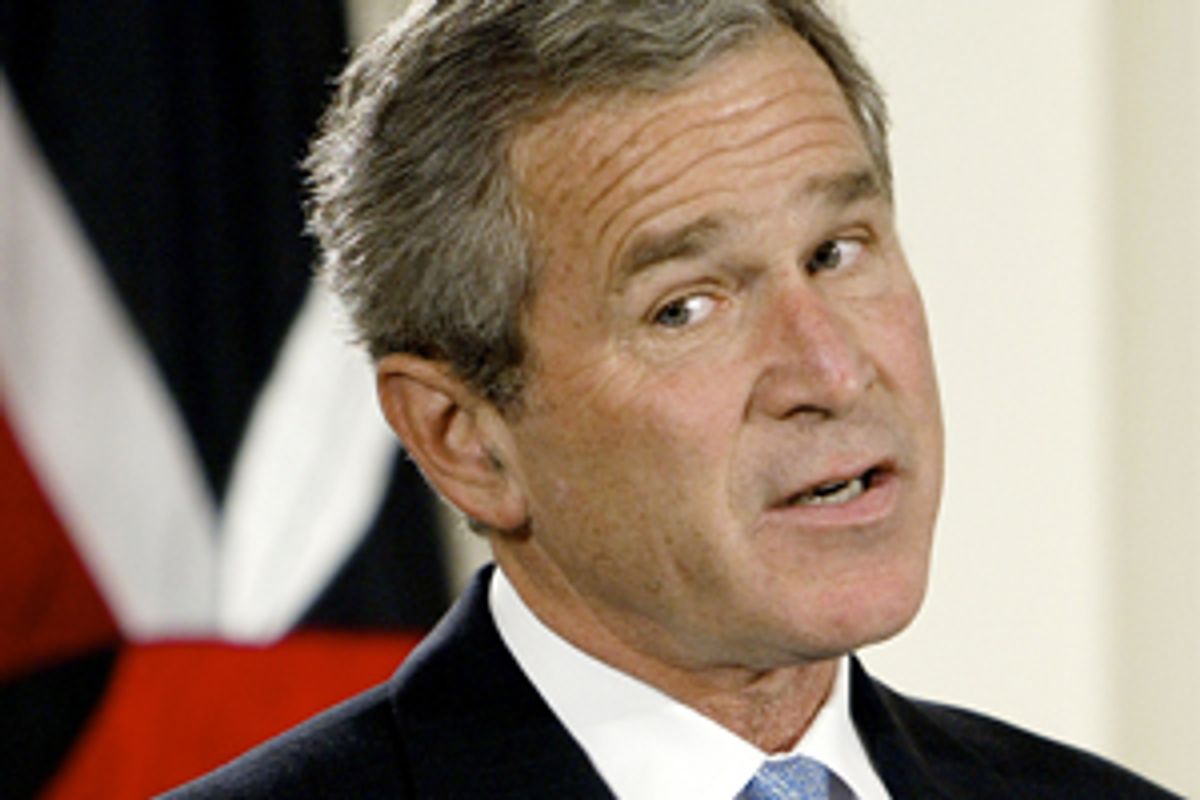

President Bush has been in search of himself for two and a half years. His voyage of self-discovery began on Sept. 30, 2003. Asked what he knew about senior White House officials anonymously leaking the identity of covert CIA operative Valerie Plame Wilson, he expressed his earnest desire to help special prosecutor Patrick Fitzgerald ferret out the perpetrators. "I want to know the truth," he said. "If anybody has got any information inside our administration or outside our administration, it would be helpful if they came forward with the information so we can find out whether or not these allegations are true and get on about the business."

Bush didn't stop there. He issued an all-points bulletin requesting help for the prosecutor. "And if people have got solid information, please come forward with it. And that would be people inside the information who are the so-called anonymous sources, or people outside the information -- outside the administration. And we can clarify this thing very quickly if people who have got solid evidence would come forward and speak out. And I would hope they would." The day before, the president had sent out his press secretary, Scott McClellan, to announce that involvement in this incident would be a firing offense: "If anyone in this administration was involved in it, they would no longer be in this administration."

Last week, however, in a filing in his perjury and obstruction of justice case against I. Lewis "Scooter" Libby, former chief of staff to Vice President Dick Cheney, Fitzgerald revealed that Libby had been authorized by the president and vice president to leak parts of the October 2002 National Intelligence Estimate on Iraq's weapons of mass destruction to reporters.

The White House's initial response was for an anonymous "senior administration official" to leak to the New York Times that Bush had played "only a peripheral role in the release of the classified material and was uninformed about the specifics," as the Times reported. The White House source, trying to remove the president from the glare, fingered Cheney as the instigator.

On Monday, Bush appeared at Johns Hopkins University's Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies, where a graduate student asked him about his role in the leak of classified information. The president, who had once perplexedly said, "I want to know the truth," replied, "I wanted people to see the truth and thought it made sense for people to see the truth." Was blind but now he sees? Grace (or Patrick Fitzgerald) had led him home.

Bush acted in the beginning as an innocent injured party. He pretended to be utterly baffled by events. His feigned unawareness was intended to deflect attention from himself. His call to find those responsible was to ensure that the facts would never be known. When he was exposed, he donned a new guise. Instead of the seeker of truth, he became the truth teller.

But the classified information he authorized to be selectively leaked -- that Saddam Hussein was seeking to purchase yellowcake uranium in Niger for use in nuclear weapons -- was not the truth, and its release was intended to buttress a falsehood. Indeed, last week, former Secretary of State Colin Powell told journalist Robert Scheer that the notorious 16 words in Bush's 2003 State of the Union address concerning Iraq's supposed efforts to buy uranium -- the claim that former ambassador Joseph Wilson was sent to Niger to investigate -- were bogus. "That was a big mistake," Powell said. "It should never have been in the speech. I didn't need Wilson to tell me that there wasn't a Niger connection. He didn't tell us anything we didn't already know. I never believed it." Thus, three years after the event, Powell finally admitted publicly that the president spoke falsely about the reason for war, that there were interested parties inside the administration determined to put false words in his mouth, and that the secretary of state, knowing this, lacked the power to stop it.

Bush as the man of truth offered a convoluted explanation of the declassification process. He retreated into technical legalisms that as the man of action he had disdained. "You're not supposed to talk about classified information, and so I declassified the document," he said at Johns Hopkins. "I thought it was important for people to get a better sense for why I was saying what I was saying in my speeches."

Once again, he offered a misleading statement. The completely irregular process of Bush's declassification, so unprecedented that Scooter Libby was unsure it was legal, was a badge of guilt. The declassification reflected a vengeful impulse against a critic and was an inadvertent confession of the fragility and tenuousness of Bush's case for war.

Fitzgerald's filing of April 5, the cue for Bush's latest theater of the absurd, provides previously lacking details of the narrative. Through Fitzgerald's further filings before the January 2007 trial of Scooter Libby, other crucial facts may yet emerge. In his prosecution of Libby, Fitzgerald is establishing indisputable facts about the history of the Bush presidency and its methods of operation.

Fitzgerald writes that the Office of the Vice President viewed Wilson's revelation of his mission to Niger and what he didn't find there "as a direct attack on the credibility of the vice president (and the president) on a matter of signal importance: the rationale for the war in Iraq." So, Fitzgerald continues, the White House undertook "a plan to discredit, punish or seek revenge against" Wilson that included as one of its elements outing the covert identity of his wife. The "concerted action" against Wilson was centrally organized and directed. The prosecutor writes that he has gathered "evidence that multiple officials in the White House discussed her employment with reporters prior to (and after) July 14 [2003]" -- the date her activities tracking weapons of mass destruction for the CIA were compromised by being publicized by conservative columnist Robert Novak. (Full disclosure: Joseph Wilson and I became friends when we worked together in the Clinton administration.)

While one part of the "concerted action" was to attempt to damage Wilson by attacking him through his wife, another was to manipulate the press to undermine Wilson's credibility. Cheney ordered Libby to act as the leaker. The plan, according to Libby's testimony, was to "disclose certain information in the NIE" to New York Times reporter Judith Miller. Libby and Miller had worked this way before when she had published a series of stories asserting that Saddam Hussein possessed WMD based on leaks she received and that were in circular fashion cited by the administration as authoritative reports by the "newspaper of record." Libby testified that he was directed to leak to her that the NIE "held that Iraq was 'vigorously trying to procure' uranium."

In the setup for the leak, Fitzgerald writes, Cheney "advised defendant that the President specifically had authorized defendant to disclose certain information in the NIE" and that that approval was a secret. Libby was a team player, but he was also anxious about a declassification that was "unique in his experience."

The formal rules for declassification were amended by Bush's Executive Order 13292 of March 25, 2003, on "Classified National Security Information." Under any circumstances the president has the authority, as he always has, to unilaterally declassify official secrets and intelligence "in the public interest." But a decision to declassify a document normally passes through the originating agency and then through the Office of the National Security Advisor. Then the document is stamped declassified and the declassified order is appended to the document.

None of these procedures was followed in this case, which is why Libby's antenna was gyrating. He sought the advice of Cheney's counsel, David Addington, Libby's close ally. In approaching Addington, Libby must have known what he would hear. Addington is the foremost legal advocate in the White House of the idea that the president should be unbound, unchecked, unfettered in his authority, whether in the torture of detainees, domestic surveillance or any other matter. Unsurprisingly, Addington "opined that presidential authorization to publicly disclose a document amounted to a declassification of the document."

Only four people -- Bush, Cheney, Libby and Addington -- were privy to the declassification. It was kept secret from the director of central intelligence, the secretary of state and the national security advisor, Stephen Hadley, among others. Indeed, Hadley was arguing at the time for declassification of the NIE but was deliberately kept in the dark that it was no longer classified. Fitzgerald writes about Libby: "Defendant fails to mention ... that he consciously decided not to make Mr. Hadley aware of the fact that defendant himself had already been disseminating the NIE by leaking it to reporters while Mr. Hadley sought to get it formally declassified." Having Hadley play the fool became part of the game.

On July 8, Libby met with Miller. In a dance of mutual deception, Libby misrepresented the contents of the NIE, which Miller apparently accepted at face value, as she had accepted such leaks in the past. With an air of mystery, telling Miller she should identify him in her story as "a former Hill staffer," Libby vouched for a document some of whose information he knew to be false, failing to note that the NIE notably did not prove that Saddam was seeking uranium in Niger; on the contrary, the NIE contained a caveat from the State Department's Intelligence and Research Bureau saying that the rumors "do not, however, add up to a compelling case." For her part, Miller thought she was receiving classified, not declassified, material, as she wrote later in her post-prison account in the Times.

Ten days after their meeting, which did not result in a story, the already declassified NIE was formally declassified as though it had never been declassified. The date of its declassification in the official government record, in fact, reads July 18, 2003, not the date that Bush declassified it for the purpose of Libby's leaking.

After the launch of the federal investigation, Libby became frantic. He knew that he had leaked Valerie Plame Wilson's identity and that others had, too, and he wanted to be protected. Fitzgerald writes that "while the President was unaware of the role that the Vice President's Chief of Staff and National Security Adviser had in fact played in disclosing Ms. Wilson's CIA employment, defendant implored White House officials to have a public statement issued exonerating him." But there was no forthcoming statement. Libby implored Cheney "in having his name cleared." But Cheney did nothing for his henchman. In a White House that demands impeccable loyalty, loyalty was not being returned.

Libby not only knew that Hadley had leaked Plame's identity; he also knew that Karl Rove, the president's principal political advisor, had leaked her name to Novak. Libby linked himself to Rove in his desperate coverup. He gave press secretary Scott McClellan a handwritten note, almost in the form of a haiku. It read:

People have made too much of the difference in

How I described Karl and Libby

I've talked to Libby.

I said it was ridiculous about Karl

And it is ridiculous about Libby.

Libby was not the source of the Novak story.

And he did not leak classified information.

On Oct. 4, 2003, McClellan informed the White House press corps that Rove and Libby (and National Security Council staff member Elliott Abrams) were innocent of the charges of leaking Plame's name -- "those individuals assured me that they were not involved in this."

Then Libby appeared before the grand jury, where he several times claimed under oath that he learned about Plame's identity from reporters. On Oct. 28, 2005, he was indicted for perjury and obstruction of justice.

Fitzgerald's filing demolishes Libby's projected defense as a busy man with so many important matters of state on his mind that he just can't remember exactly who told him what about Plame. Here, in his own words, Libby recalls precisely his anxiety about the "unique" declassification and the others who leaked Plame's name. Libby may now wonder why he should play the fall guy, unless the scenario is to hope for a presidential pardon on the morning of Jan. 20, 2009, the day Bush leaves office.

President Bush, having previously play-acted as unknowing, is now engaged in the make-believe that he is helping people "see the truth." Yet the White House refuses to declassify the one-page summary of the NIE used to brief Bush. Presumably, it contains the caveats from various intelligence sources on Saddam's WMD, showing that the case remained unproved and shaky when Bush presented it as conclusive.

The White House also refuses to release the transcripts of Bush's and Cheney's testimony before the prosecutor. As witnesses they are not bound by any rule of secrecy and are free to discuss their testimony publicly. During the Watergate investigation, the Supreme Court ruled unanimously that President Nixon had to turn over his secret audiotapes to the prosecutor. Fitzgerald obviously already has the White House transcripts. Only the public is uninformed of their contents. Why won't the White House release them now? Indeed, there is a precedent. On June 24, 2000, then Vice President Al Gore made public his testimony to the Justice Department investigation into campaign finance. (While Bush and Cheney insisted on giving testimony without being sworn under oath, they remain legally liable. Under Title 18, Section 1001 of the U.S. Code, anyone who testifies falsely in a federal inquiry may be fined and sentenced to five years in prison.)

Bush is entangled in his own past. His explanations compound his troubles and point to the original falsehoods. Through his first term, Bush was able to escape by blaming the Democrats, casting aspersions on the motives of his critics and changing the subject. But his methods have become self-defeating. When he utters the word "truth" now most of the public is mistrustful. His accumulated history overshadows what he might say.

The collapse of trust was cemented into his presidency from the start. A compulsion for secrecy undergirds the Bush White House. Power, as Bush and Cheney see it, thrives by excluding diverse points of view. Bush's presidency operates on the notion that the fewer the questions, the better the decision. The State Department has been treated like a foreign country; the closest associates of the elder President Bush, Brent Scowcroft and James Baker, have been excluded; the career professional staff have been bullied and quashed; the Republican-dominated Congress has abdicated oversight; and influential elements of the press have been complicit.

Inside the administration, the breakdown of the national security process has produced a vacuum filled by dogmatic fixations that become more rigid as reality increasingly fails to cooperate. But the conceit that executive fiat can substitute for fact has not sustained the illusion of omnipotence.

The precipitating event of the investigation of the Bush White House -- Wilson's disclosure about his Niger mission -- was an effort by a lifelong Foreign Service officer to set the record straight and force a debate on the reasons for going to war. Wilson stood for the public discussion that had been suppressed. The Bush White House's "concerted action" against him therefore involved an attempt to poison the wellsprings of democracy.

Shares