All the alleged hipness and glamour of the Tribeca Film Festival were in full effect on a busy weekend of premieres and showcases, but neither glorious weather nor the celebrity sightings that New Yorkers must pretend they don’t notice or care about has been able to dispel the funereal mood emanating from the films themselves.

Around the Tribeca Grand Hotel, festival ground zero, the atmosphere feels the same as ever: Doormen give you an imperceptible nod behind their Erik Estrada aviator shades; random semi-famous people (Jeff Goldblum, Mos Def, John Malkovich) drift through the lobby bar; and sooner or later you end up in one of the extraordinary bathrooms, trying to pee into a tiny steel vitrine while standing in a mirrored alcove lined with turquoise tile (the effect is part Spanish-colonial church, part ’70s coke flashback). Then you see a movie and the good times pretty much evaporate.

I’m being facetious, but then again, no, I’m not. Maybe it’s just a cosmic accident, but this festival has tapped into some deep vein of gloom with no obvious source. The dreariness of our civic and political life late in the Bush era? The slow-dawning realization that independent film is just a kooky niche genre, not unlike fantasy baseball or those books about war my father-in-law reads, only less profitable? The fact that we all know that paying $3.50 a gallon is just a symptom, and what it’s a symptom of might well be a planetary terminal illness? Well, all right, those are candidates.

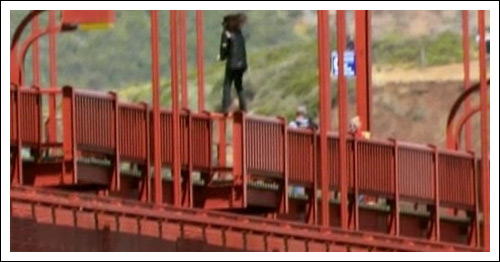

I will not, however, make any jokes on the subject of ending it all. Nearly every picture I’ve seen here makes some reference to suicide, and you can make of that what you will. If the film that grabbed my attention last week was “Jonestown: The Life and Death of People’s Temple,” this weekend’s stunner was Eric Steel’s “The Bridge,” which documents a year of life and death on America’s landmark to suicide, the Golden Gate Bridge. (It premiered almost simultaneously at Tribeca and at the San Francisco International Film Festival.) I still have unanswered moral questions about the film — unanswered because unanswerable, I suspect — but it’s a beautiful, wrenching, horrifying work of cinema, unlike anything I have ever seen or will see again.

Steel’s method has attracted considerable attention: He filmed the bridge during every possible daylight hour for an entire year, from a couple of vantage points on the San Francisco side. One was simply a fixed, wide, “postcard” shot, to ensure that no event occurring anywhere on the bridge during that year would be missed entirely. At the other station, Steel had a camera with a super-long telephoto lens, capable of identifying and following individuals as they walked along the eastern pedestrian pathway. (This isn’t discussed in the film, but that’s where almost everyone jumps. Perhaps paradoxically, people generally choose to die looking back at civilization, rather than out at the open Pacific or the sunset.)

During that year, which was 2004, 24 people jumped off the Golden Gate Bridge and died. That’s a typical number. Steel and his camera crews witnessed and photographed most of them. The answer to your next question is yes, we see jumpers in the film. Several of them, in fact. Within a few minutes, viewers of the film will become uncannily skilled at picking out likely jumpers in Steel’s images: People on the bridge who are alone, lingering, doubling back, a bit too inwardly focused, acting a little off. And I don’t care how jaded or steeped in televised pseudo-reality you are; it’s profoundly, even inexplicably shocking to see a person, for all the world an ordinary walker out on a beautiful day in one of the world’s most dramatic settings, step out of the flow of joggers and bicyclists and slip over that railing.

If Steel were just showing us strangers killing themselves, as in some nightmarish Fox series, then no amount of ironic or aesthetic context could redeem his film. He’d just be selling shock value, or death porn, and pretty soon we’d get bored with it and want something even more extreme. (Are there other bridges with longer drops? What about jumpers who miscalculate and hit the bridge pilings instead of the water?) Opinions about “The Bridge” are sure to vary widely, but it seems clear that Steel’s intentions are honorable. He understands that after capturing these people in a moment of final, public despair he owes them something.

(Steel and his camera operators called the authorities whenever they saw people on the bridge display warning signs: Staying too long in one place, staring too long at the water, exhibiting emotional distress, removing clothing or backpacks. During that year, he says, “We were almost always the first people to call when someone was about to jump, or had jumped,” and he believes they helped save several people’s lives. Furthermore, he says, every jump or near-jump they filmed was a public event, occurring in daylight in front of numerous witnesses. It wasn’t like they were clandestinely photographing people in their homes.)

The heart of “The Bridge” (which was inspired by Tad Friend’s October 2003 New Yorker story “Jumpers”) does not lie in the footage of jumpers or maybe-jumpers or prevented jumpers — we witness one astonishing rescue by an ordinary citizen — but in the interviews Steel did later with friends and family members of the dead, or with people who had seen them or spoken to them on the bridge. “What we see in people’s homes,” Steel told a press conference after the screening, “is more personal and intimate than what we see on the bridge.” That is never more clear than in his interviews with Kevin Hines, a young man battling severe mental illness who belongs to a select group: Golden Gate Bridge jumpers who survive to tell us about it.

For the divided and anguished family of 44-year-old Lisa Smith, a diagnosed paranoid schizophrenic with various other illnesses, her trip to the bridge was a chapter in a long, painful history that clearly has not ended, even after her death. On the other hand, the parents of 22-year-old Philip Manikow seem almost too accepting; he was a determined and devoted suicide planner despite all their efforts to intervene, and they had no doubt he would succeed eventually.

A friend of 52-year-old Daniel “Ruby” Rubinstein is haunted by the fact that she gave him a stash of unprescribed antidepressants — which can have unpredictable effects on unstable people — and refused to let him sleep over the night before he jumped. (She is the only interviewee who appears anonymously.) But the friends of 34-year-old Gene Sprague, a Goth-metal dude with a flair for drama whose story becomes the narrative spine of “The Bridge,” are pissed. They assumed all his talk about suicide was bullshit, and on the day he jumped, there was a call on the machine offering him a management job in a video-game store.

Steel compares his film, or at least the spectacular images it captures, to Brueghel’s painting “Landscape With the Fall of Icarus,” and if that sounds unbelievably grandiose, you haven’t seen it. As in the painting, there’s an incredible tension between the beauty of the scene and the private tragedy captured in it, unnoticed by almost anyone. There are moments in “The Bridge” when someone has gone over the railing, and is teetering on the narrow construction deck on the other side, literally balanced between life and death — and people ride or stride right past, not noticing or not caring or just not thinking about it.

Even that is not quite Steel’s most haunting image. (I won’t tell you about his most dramatic image, but you’ll know it’s coming for most of the film.) There were several suicides that year that his telephoto operators missed for various reasons, and he shows us a couple of those from the wide shot: the bridge, against that impossible California sky. Cars nosing along, the tide below pushing and swirling. Pelicans, boats, wave riders. Then an object, too small to make out, falling for about four seconds. Then a splash. Then nothing.

It’s unfair to put your average indie narrative feature up against something as intense and potentially controversial as “The Bridge.” So far, with a few foreign exceptions (I loved “Backstage” and “The Yacoubian Building,” and the buzz on the Croatian film “Two Players From the Bench” is strong), average is about what we’re getting on the fiction side at Tribeca. What I mean by that is well-intended films with agreeable elements, some level of ambition and some evidence of artistry — some idiosyncratic somethingness, at least — but not enough to make them memorable or distinctive.

All three major world premieres this weekend are at about that level. In “Color Me Kubrick,” John Malkovich has a delicious turn as Alan Conway, a low-rent English con man, now deceased, who dined and drank his way across London for a while by pretending to be Stanley Kubrick. As Malkovich discussed after the press screening, the sheer outrageousness of Conway’s ruse makes him an appealing character: He’d never seen a Kubrick film all the way through and knew almost nothing about him, and Conway’s attempt at an American accent was laughably bad. (Malkovich didn’t mention this, but Conway was also a flamboyant gay man with a taste for rent boys and trashy nightclubs, while Kubrick was married and famously reclusive.)

In playing Conway, Malkovich says, he employed the esoteric acting tradition of “making it up as you go along.” His accent as Conway-as-Kubrick is deliberately unstable, veering from the Bronx to Louisiana to the London suburbs within a few seconds. “There are scenes when the accent is a little bit Yiddish, a little bit Croydon, a little bit Copenhagen and a little bit Seoul,” Malkovich says. “I spent a lot of time rehearsing with a tape recorder so it would sound like someone very confidently making mistake after mistake.”

Malkovich is of course an international signifier for intelligent cinema, and this showboat performance is certainly worth seeing. Curiously, it does little to redeem director Brian Cook’s film, which is often funny but never rises above campy, mean-spirited trash. (For those who don’t know much about Kubrick’s career or about the odd British class-system politics involved in Conway’s deception, it will also seem pretty pointless.) Even Malkovich seems to see this when he describes his initial reaction to the “outrageous and idiotic” costumes designed for Conway: “Can one person get away with wearing all this? Is that actually a character?”

Todd Robinson’s “Lonely Hearts” stars John Travolta and James Gandolfini as a pair of sour Long Island homicide detectives, circa 1948, and Jared Leto and Salma Hayek as the murderous lovebirds they’re pursuing. How does a crime film with that cast (not to mention real-life historical roots) make it this far without a distributor? Well, on one hand, Tribeca may actually be becoming a major marketplace festival. On the other, “Lonely Hearts” is a handsome and well-acted film — if you like that bitten-off, half-Hemingway style — but also a grim, emotionally strangled one with a strong sadistic current, no genuinely likable characters and almost no humor.

From the very first scene, key back-story elements and plot points are delivered in voice-over narration (by Gandolfini’s character), which is generally a sign that the narrative has defeated its author. It should be a lot more fun to see the guy who was Tony Manero and the guy who is Tony Soprano, together at last, than it turns out to be. It’s almost like their characters are too realistically drawn; Travolta’s character is paralyzed by his wife’s suicide (our theme again) and Gandolfini’s is so inscrutable he makes Tony Soprano seem like a weepy New Ager. Both of them attempt versions of that slow-burn De Niro performance that just makes lesser actors (and sometimes De Niro himself) seem like your uncle with gastric reflux.

There are no such problems for Leto and (especially) Hayek, who chew the scenery into a fine-grained, blood-flavored paste. I don’t know whether the real “Lonely Hearts killers” of the ’40s were motivated by the same sexual urgency as this couple — while Ray (Leto) seduces wealthy widows, Martha (Hayek) poses as his sister, brewing furious jealousy and insatiable desire — or whether the real Martha was “the hottest bitch you’ve ever seen,” to use her phrase. But it gets a lot harder to love these whacked-out love-bunnies when they start torturing lonely women to death and sawing up small children. Call me squeamish.

“The TV Set,” a showbiz satire from writer-director Jake Kasdan (son of Hollywood veteran Lawrence Kasdan) has a pretty good script and the odd sparkling moment. Or maybe it’s the show-within-a-movie, the TV “dramedy” being developed by Mike Klein (David Duchovny) for a scum-sucking network that already has shows on the air called “Slut Wars!” and “Skrewed,” that’s pretty good. I can’t quite tell. I can tell that Kasdan — who developed the show “Freaks and Geeks” — is spinning his real stories from a life in the television trenches, and I can also tell that he’s undercut his movie by miscasting it.

My theory about Duchovny is that he’s got to quit playing likable, driven, principled guys. Anything else will do: a homeless man, a couch-potato roommate, a creepy Birkenstock husband, a Klansman, Charles Manson. Here he pretty much just groans and stares at the furniture while indignities are piled upon Mike’s show by a simultaneously dumb and slimy programming exec (Sigourney Weaver). The affectless Duchovny demeanor that stuck out so much playing Agent Mulder on TV makes him seem like a mournful, bearded side of beef here. (See also: Caruso, David, film career of.)

Weaver is also miscast, although the results are quite different. She’s not really the big comedienne type this role demands, and plays the whole thing with an air of cheerful, WASPy sportsmanship that makes you hope that the embarrassing sketch will soon end, and we can move on to “Weekend Update” or a song by Green Day. These two antagonists are so wobbly that it’s hard to tell how sharp Kasdan’s premise and writing really are: I’m pretty sure he’s just restaged Tom DiCillo’s “The Big Picture” to the TV world, which also means less original and not half as funny.

Like so much cultural satire, “The TV Set” can’t outrun its target. Mike’s show is recast with a goofball lead, has its suicide subplot (ding! ding! ding!) erased and is retitled “Call Me Crazy!” But does that — or “Slut Wars!” for that matter — even register anywhere near the top of TV’s moron meter? This is a tepidly amusing film that will offend no one, including those it claims to skewer.