In the days and weeks following Sept. 11, 2001, the purveyors of American popular culture promised us a gentler, more reflective future. In the aftermath of the attacks, movies and television shows were scrubbed of fireballs and scenes of gratuitous mayhem; scriptwriters became somber, subdued and thoughtful. It was a refreshing experiment, despite the occasional needless displays of political correctness and self-censorship. We seemed eager to embrace a more nuanced look at ourselves and our world.

Or maybe I just imagined it, for all of this, inasmuch as it occurred, was decidedly short-lived. And when the pendulum came careening back, it swung well beyond neutral to a position of unrelenting crudeness -- where it remains today, solidly fixed. One can argue whether the existing state of mass entertainment, from books to films to talk radio, is in fact more mindless and coarse than in years past, but one thing is certain: Whatever sensitivities we affected in the wake of our Great National Trauma have been traded down for an unwavering acceptance of hedonism and violence -- both fictionalized and otherwise -- coupled with a bottomless appetite for melodrama.

It would only be fitting, therefore, that "United 93," as Hollywood's first true Sept. 11 movie (Michael Moore's documentary doesn't count), come in one of two forms: either a jingoistic, over-the-top spectacle, or yet another maudlin stoke of our seemingly endless collective suffering.

Except it is neither.

"Tasteful" is the word being spun by critics and pundits. Of course, there are different ways of being tasteful, not all of which are acceptable to everyone. If you ask me, Paul Greengrass' re-creation of the events aboard the skyjacked United Airlines 757, shot with a low-budget cast of nobody actors, including real-life pilots, flight attendants, military officers and air traffic controllers, is nothing if not triumphantly unpretentious. The skeletonized dialogue and jittery, claustrophobic camerawork create an atmosphere that is realistic almost to a fault. As a viewer, you feel as if you're peering into the cabin of the actual doomed airplane -- as though you've been sucked into the black box recorders and forced to bear witness to the horror as it unfolds, the theater itself wallowing aloft in the same unthinkable predicament. It's so raw that you come away battling pangs of voyeuristic guilt.

Thus, "United 93" winds up feeling like a cross between a motion picture and 90 minutes of therapy -- the kind of movie we should see, in that civic obligation sort of way, rather than the kind we might actually enjoy. There's not a lot to learn from this story; every last person in the audience knows exactly what is going to happen. The movie meanders back and forth across the line separating documentary reenactment from full-blown drama, never quite committing either way. But there's a grit -- a vicious, real-time tension -- that serves to heighten rather than undermine the crescendo. Virtually every scene is hewed to a sharp and frightening simplicity, blissfully free of the usual cinematic bloviations. (One exception being the soundtrack. I wish Greengrass had done as director Sidney Lumet did in 1975 with "Dog Day Afternoon," allowing the tension to build, and ultimately release, without any use of music whatsoever.)

Sadly, time will surely have its way with such deferential modesty. It is all but inevitable that later tackles of Sept. 11 will be less restrained. Greengrass deserves no small praise for getting the first one right by keeping it compact -- albeit he had little choice. My earlier condemnations notwithstanding, and at the risk of giving audiences too much credit, our 9/11 hangover has hardly subsided, and overcooking things may have resulted in great collective scorn.

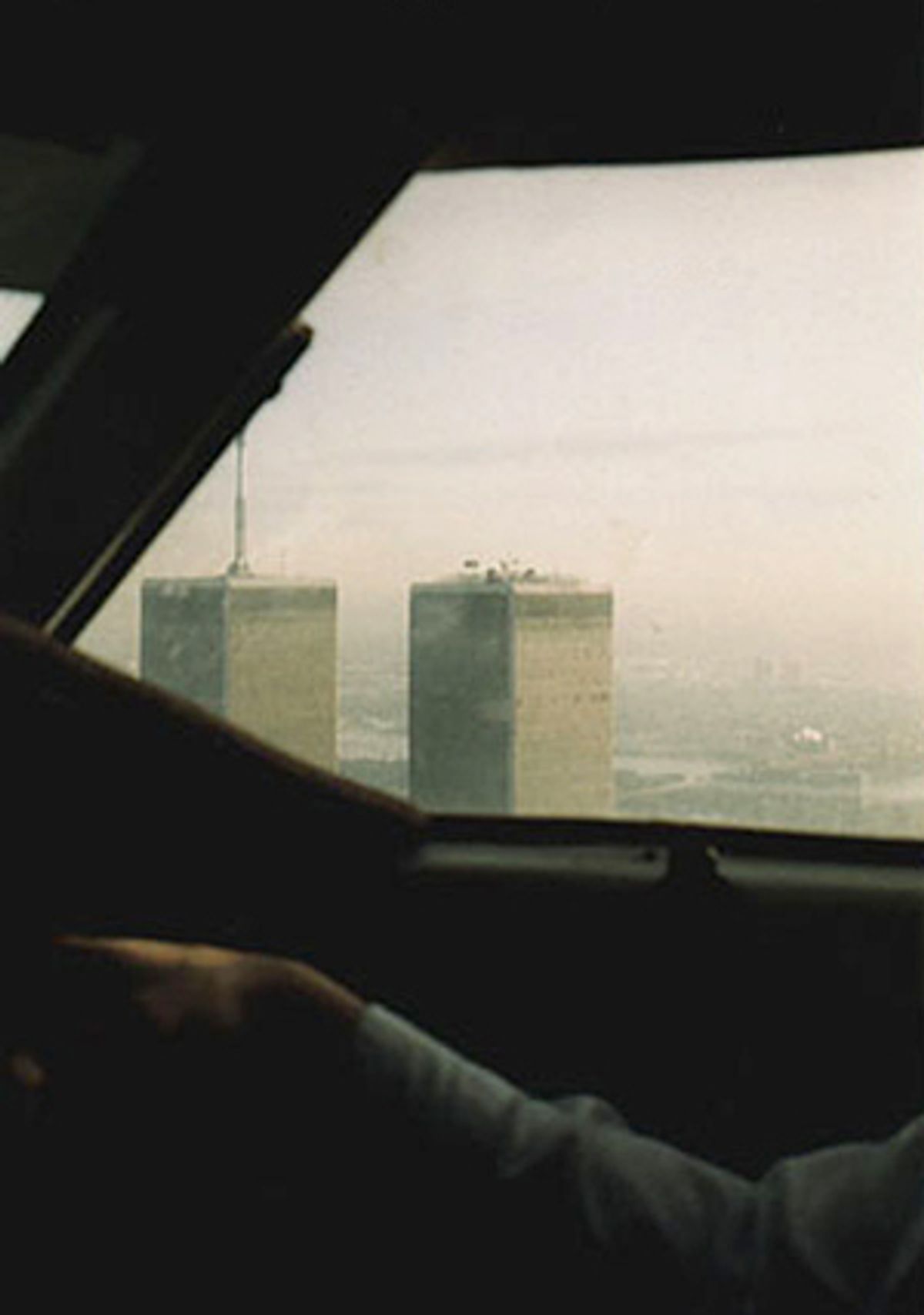

As a moviegoer with a marked distaste for cloying dramatizations, and as a pilot with equal distaste for technical bloopers, I found "United 93" to be without a doubt the best airplane movie I've ever seen -- though, as we know, there's not much of a well to draw from. At their best, airplanes in film are not onscreen to represent themselves. Rather, their presence is symbolic or metaphorical, as the journey that is the essence of so many stories. Thus, the most meaningful glimpses of planes are the furtive, incidental ones -- the background shots of a silver-skinned 707; the requisite screech of tires hitting a runway. Once the airplane becomes the central setting, expectations deservedly plummet. Disaster films like the 1970s "Airport" series, or any of more recent blockbusters, are such lousy artistic products, and so laden with distortions and inaccuracies, that pilots and nonpilots find them tedious and unwatchable. Satirical spoofs, like the '79 classic "Airplane," tend to be more palatable by the simple virtue of not asking us to take them seriously.

In this regard, "United 93" succeeds where almost every other movie fails. For the record, I counted about 15 minor gaffes, ranging from poorly rendered air traffic control lingo to an errant shot of an Airbus A320 standing in as the United 757. But the reconstructions are, if not flawlessly spot-on, close enough to keep a known pedant like me from listing the bloopers here. Even the background chatter between pilots and air traffic controllers is, in many instances, taken verbatim from actual ATC recordings. The overall lack of miscues is doubtless owed to the use of actual controllers and air crew staff as cast members, including United Airlines pilot J.J. Johnson as Capt. Jason M. Dahl. The most touching bit of realism may be the moment when, preparing to eat his breakfast in the cockpit, first officer LeRoy Homer, played by commercial pilot Gary Commock, removes a bottle of hot sauce from his flight kit. I smiled at that, familiar with the popularity of those little red bottles among fliers -- a requisite flight bag item no less crucial than maps, charts and manuals.

"I went to this movie to see LeRoy Homer again -- or Lee, as we knew him -- hoping the filmmakers portrayed him correctly," Deb Ings, a United Airlines captain and colleague of Homer's in the Air Force Reserve, told me. "Gary Commock seemed to 'get' Lee -- even if he looks nothing like him. Television depictions of flight 93 show him as a bit too happy-go-lucky. In truth he was reserved and intelligent, with a dry sense of humor."

But the attempt to play things as straight and true as possible is nearly the movie's undoing. By taking the dramatic high road and going to such lengths to ensure accuracy, "United 93" also had an obligation to follow the real-life script as closely as possible. In the closing scene it goes astray, strongly embellishing the final seconds of the jet's deadly dive.

According to the cockpit voice recordings, as described in the 9/11 Commission report, passengers did not make it into the plane's cockpit, much as they were trying. They are heard ramming what sounds to be a galley cart against the door when the skyjackers decide to crash the plane. On tape, terrorist pilot Ziad Jarrah and at least one henchman are heard discussing their predicament, and what they intend to do about it: "Shall we put it down?" Ziad then pushes the control wheel forward and snaps it to the right, flipping the 757 onto its back and into a disintegrative plunge toward an empty field in Pennsylvania. In the movie version, nobody asks "Shall we put it down?" (though possibly this is spoken in Arabic, as subtitles are kept to a minimum). Instead we witness a splintering door and a panicked frenzy, with passengers battling Ziad for control.

The filming of the dive scene is somewhat muddled and ambiguous, but it's clearly implied that passengers have made it through the door. Which, in the commission's opinion, did not happen. It's hard to understand why this liberty was taken -- the finale would be no less gripping had they played it true.

For the most part, to its final moment, "United 93" stays within remarkably tight boundaries of restraint and, give or take a few frames, accuracy. In the end, regardless of the movie's overwrought final seconds, it's plainly obvious there were no real heroes aboard flight 93 -- at least as we've come to understand that label in these times of hyper-patriotic fervor -- only desperate people trying valiantly to save themselves. It's good for us, as a country, to see that.

GO-AROUNDS

Re: Security detail

A clarification: Several readers took issue with Andrea Pertosa's letter -- as well as my published response to it -- about shorter airport security lines for first- and business-class passengers. I believe Pertosa was seizing the chance to make a small joke -- "a trip to martyrdom is always better in first than economy." Neither she nor I meant to imply that premium-class customers received less intensive screening (though I'm told that in some countries this indeed is the case). Screening standards are the same for all passengers, regardless of which lines they use.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

Do you have questions for Salon's aviation expert? Send them to AskThePilot and look for answers in a future column.

Shares