Months before Abu Musab al-Zarqawi was killed by a U.S. airstrike, American military commanders and intelligence officers in Iraq battled Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld and the White House to “degrade” the terrorist’s dramatically inflated image, while Rumsfeld and the White House resisted, ultimately for “domestic political reasons,” as a military source involved in this internal controversy told me. In the end, the military lost.

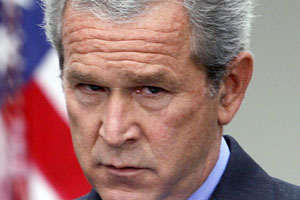

President Bush’s June 8 statement on Zarqawi’s death the night before described him as “the operational commander of the terrorist movement in Iraq,” “one of its most visible and aggressive leaders,” and his death as “a severe blow to al Qaeda.” But the president said “we can expect the terrorists and insurgents to carry on without him.” Superficially sober, Bush’s remarks conflated the lone wolf Zarqawi not only with al-Qaida — though Zarqawi had seized on the al-Qaida label as self-proclaimed grandiosity and al-Qaida leader Ayman al-Zawahiri had earlier denounced his extreme tactics — but also with the entire Sunni insurgency, with which Zarqawi had been in conflict and which well might have been responsible for betraying him. Bush’s rhetorical account was an implicit dismissal of U.S. intelligence.

If Zarqawi’s killing was a new version of Saddam Hussein’s capture (“We got him!”), Bush’s surprise visit to Baghdad on Tuesday was “Mission Accomplished” in a business suit. Six months after the Iraqi election, with Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki at last having appointed defense and interior ministers amid sectarian civil war, Bush declared, “They themselves have to get some things accomplished.” One thing Bush was attempting to accomplish was a reversal of his own political fortunes. Zarqawi’s death had provided a convenient platform for the unfolding of his scripted theater featuring a two-day Camp David retreat of his war cabinet, the midnight flight to Baghdad and repeated references to Sept. 11, but no broad new initiatives for a political solution.

President Bush, in a speech on Oct. 7, 2002, making the case for invading Iraq, first introduced Zarqawi to the world as Exhibit A in Saddam’s “links to international terrorist groups … We know that Iraq and al Qaeda have had high-level contacts that go back a decade.” (A CIA report made public in October 2004 found no evidence of any “links” between Saddam and Zarqawi, who in any case did not operate in Iraq until after his release from a seven-year sentence in a Jordanian prison in 1999.)

Since the rise of the Iraqi insurgency, U.S. military intelligence had been directed to build up Zarqawi’s profile as its leader through a psychological warfare (“psy-op”) effort. On April 10, the Washington Post reported on internal military documents it obtained about this psy-op: “The documents explicitly list the ‘U.S. Home Audience’ as one of the targets of a broader propaganda campaign.” According to talking points in a 2004 briefing, the goal was: “Villainize Zarqawi/leverage xenophobia response.” One military intelligence officer involved stated that Zarqawi’s followers were “a very small part of the actual numbers” of insurgents, but this had little bearing on the program. Another officer concluded, “The Zarqawi PSYOP program is the most successful information campaign to date.”

The depth and breadth of the insurgency are depicted in a new documentary, “Meeting Resistance,” that has not been publicly released. It is directed by Molly Bingham, an American journalist who was briefly jailed in Abu Ghraib by Saddam’s regime at the onset of the U.S. invasion, and Steve Connors, a British journalist. This breakthrough film, the single most astonishing documentary yet on the Iraq war, portrays a full range of insurgents, from fighters to spies to imams, speaking in their own voices, explaining their motives and actions, from the first days of the insurgency onward. “I began to see something, that we had become an occupied country,” says one who became a warrior. It is as though “The Battle of Algiers” had been shot from the inside, from the point of view of the insurgents, and not played by actors. Among other revelations, insurgents express their hostility in 2004 to Zarqawi as an obstacle to unity against the occupation but not as an impediment to the insurgency’s popular growth. “So now,” says an insurgent, “whether Zarqawi is captured dead or alive has no impact.”

Bush’s latest effort to foster belief in a “turning point” may trap him within his own psy-op. Unless Bush successfully includes the Sunnis in the political process and creates a new internationalized diplomacy, he will remain narrowly circumscribed by the consequences of his accumulated failures. Burdened by years of misjudgment, disinformation and delusion, Bush has again risked committing the blunder of raising expectations followed by deeper disillusionment within the “U.S. Home Audience.”