In "Wordplay," Patrick Creadon's affectionate, charmingly woolly documentary about the New York Times crossword puzzle and the word nuts who love it, Jon Delfin, a professional musician and crossword-puzzle champ, says plainly, "Give me blank spaces and I want to fill them in." Doing the crossword puzzle -- particularly the New York Times puzzle, which progresses from Shaker straightforwardness on Mondays to wild Rococo difficulty on Saturdays -- is ostensibly a simple pleasure, one that requires only the paper, your brain and a pencil (although, of course, braver souls prefer to use a pen). But that simplicity is deceptive: "Wordplay" suggests how easy it is to get lost in these miniature worlds of boxes and black squares. Even though these puzzles are mapped out with utmost precision -- and even though logic is an extremely useful tool for solving them -- they're still, somehow, objects of intrigue and mystery.

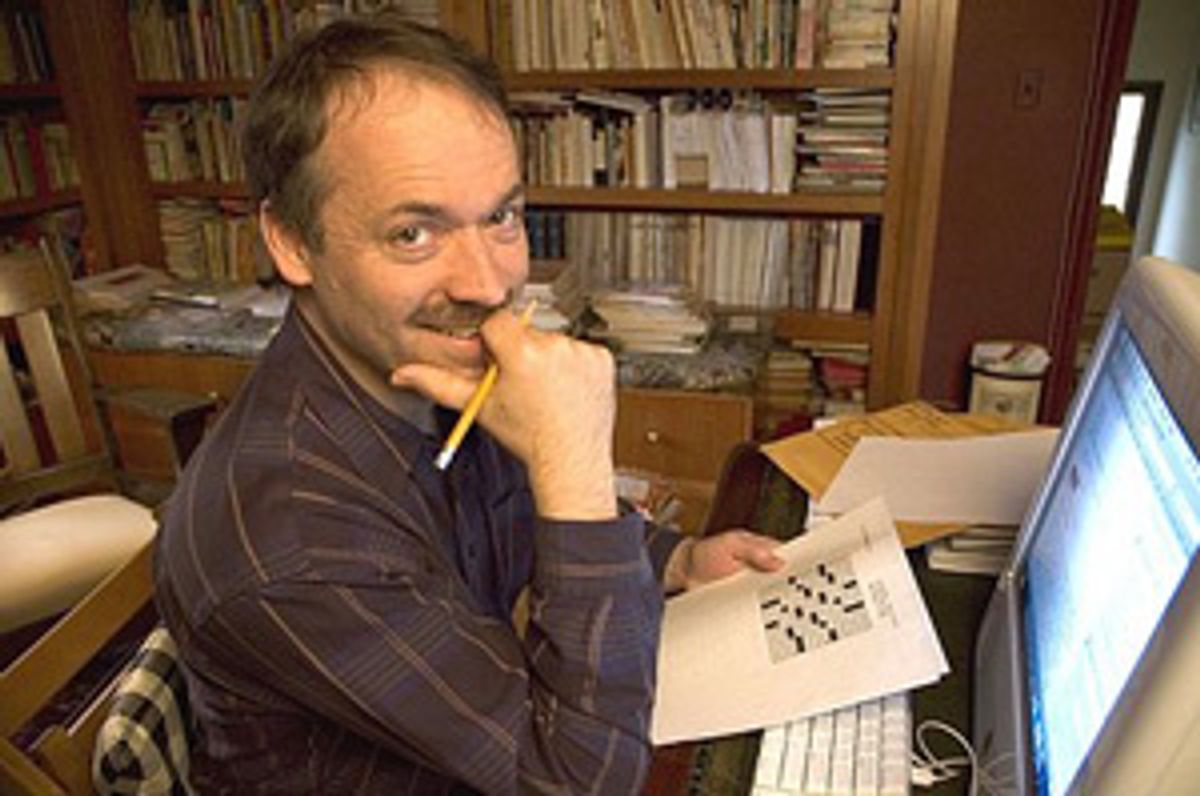

The man behind the mystery, as he's revealed to us in "Wordplay," is Will Shortz, editor of the New York Times puzzle. (He's also the "Puzzle Master" of National Public Radio.) Shortz doesn't write the puzzles himself; he relies on a cadre of professional puzzle "constructors," a few of whom are interviewed here. But crossword fans consider him responsible for all the pleasure and anxiety elicited by those empty, beckoning little boxes, as their occasional outraged letters to him suggest. As one persnickety puzzler writes, questioning the accuracy of a certain clue: "Frogs leap, sir, but toads do not. They waddle."

Shortz also founded, and hosts, the annual American Crossword Puzzle Tournament, now in its 29th year, where competitors scribble and scratch away to vie for the honor of being the fastest, and most accurate, crossword-puzzle solver in the land. (And woe to anyone who declares himself finished with a puzzle only to realize he's left one empty square; in the rough world of competitive crossword-puzzle solving, that single lonely space will cost ya.)

Even though Shortz's self-imposed mandate is to tease and challenge both his loyal followers and those who might attempt a puzzle only occasionally, there's nothing sadistic-looking about him: He's a solid average-looking middle-aged guy, affable and quick and perhaps slightly mischievous. His good-natured averageness is of a piece with the humble, everyday quality of crossword puzzles, the way they become part of a pleasurable daily routine. "Wordplay" cuts to the heart of the way crossword enthusiasts feel about that routine, featuring interviews with fans like Jon Stewart (who announces to the camera that he's feeling so confident on this particular Tuesday, he's going to use a Sharpie); Bill Clinton (who says that he sometimes likes to do the puzzle over lunch, while eating by himself at home -- and whose own name was part of a particularly ingenious Times puzzle); and former Times ombudsman Daniel Okrent (who has one of the movie's driest, funniest moments, tossing away the rest of the paper as if it were just a useless wrapper for the real treasure).

"Wordplay" is Creadon's debut as a director, and it's informed both by his love for crosswords and his clear affection for the sorts of people who do them. There's the self-described "nerd girl" Ellen Ripstein, a New York editor who won the tournament in 2001 after 18 years of coming frustratingly close to the title. (Creadon shows us footage of the victory, with Ripstein leaning down from the stage to ask the judges, "Are you sure? Are you sure?" as applause thunders around her.) Ripstein is part self-effacing pussycat and part competitive tigress: While she clearly enjoys socializing with her fellow tournament participants (this a convivial, close-knit group, and many of these people have been attending for years, even if they have no hope of winning), at one point she confesses, good-naturedly, that she wouldn't be too upset if one of her rivals happened to have a canceled flight or something. And while she's modest about being a champion, she doesn't hide how proud she is. She mentions that she once had a boyfriend who put her down, and she put up with it until she found the perfect rejoinder: "Well -- what are you the best in the world at?"

The last section of "Wordplay" focuses on the 2005 tournament, held in Stamford, Conn. And while Creadon can't quite build the kind of suspense that Jeff Blitz did in the spelling-bee documentary "Spellbound" (partly because grown-ups in competition aren't quite as poignant as little kids are), he doesn't lose momentum -- the picture is crisply edited (by Doug Blush), and by the movie's last third we have enough invested in the characters to care about who's going to win.

But "Wordplay" is at its best when Creadon is burrowing deep into the world of the puzzles themselves, particularly when he sits down with puzzle constructor extraordinaire Merl Reagle. Reagle is one of those jolly guys who at first seems vaguely gruff -- a bit like Robbie Coltrane's Hagrid in the "Harry Potter" movies. When Reagle sees signs on the street, he unconsciously rearranges their letters: "Dunkin' Donuts" becomes "Unkind Donuts"; "Noah's Ark" becomes "No, a shark!" And when he sits down at a table and approaches an empty grid, first determining the symmetrical arrangement of black boxes and then starting with a few key words, we feel we're watching a master at work: The number of odd little things he has to consider in order to make a good puzzle, or even just one that simply works -- finding trouble spots where the placement of certain vowels could cause problems, for example -- may surprise even people who do these puzzles every day.

Later, Creadon uses some clever cross-cutting to show us several people working on the puzzle Reagle has created: We see both Clinton and Stewart muttering aloud, and with thinly disguised admiration, over the clue to which "ICBM" is the answer. That's just one of the myriad delights of "Wordplay": The way it portrays the Times crossword puzzle as an everyday pleasure that draws people into a kind of community. In neighborhoods and cities all over the country (and probably other parts of the world, too), there are people mulling over the same clues and scribbling out the same answers. And cursing Will Shortz, even as they anticipate what he has up his sleeve for tomorrow.

Shares