Every Bush presidency is unhappy in its own way. George W. Bush has contrived to do the opposite of his father, as if to provide evidence for a classic case of reaction formation. Rather than halt the Army before Baghdad, he occupied the whole country. Rather than pursue a Middle East peace process that dragged along a recalcitrant Israeli government, he cast the process aside.

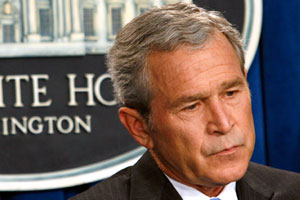

“Frustrated?” President Bush volunteered in his Monday press conference. “Sometimes I’m frustrated.” His crankiness has deeper sources than having truncated his usual monthlong summer vacation in sweltering Crawford, Texas. “Rarely surprised,” he continued, extolling his world-weary omniscience. “Sometimes I’m happy,” he plunged on, but thought better than to elaborate. “This is — but war is not a time of joy. These aren’t joyous times. These are challenging times, and they’re difficult times, and they’re straining the psyche of our country.” Then he decided he would indicate he was a calming influence, so he added, “I understand that.”

But Bush is trapped in a self-generated dynamic that eerily recalls the centrifugal forces that spun apart his father’s presidency. George H.W. Bush, a World War II fighter pilot, was unfairly said by the media to suffer from “the wimp factor,” “emasculated by the office of vice president,” according to a notorious Newsweek cover story in 1987. (George W., acting as enforcer, his then favorite role, cut Newsweek’s reporters off from further access.) It was not until the Gulf War that the public became convinced that the elder Bush was a strong leader and not the wimp he was stereotypically depicted as. But then almost immediately afterward came a recession. Bush’s feeble response was not seen as merely an expression of typical Republican policy but as a profound character flaw. If Bush was strong, why didn’t he solve the problem? The public concluded he was indifferent, and its view of him curdled into anger. Outdoing the father by subduing “the wimp factor,” the son has not grasped that it was the father’s presumed strength and not his weakness that undid him in the end.

President Bush’s staggering mismanagement of the Iraqi occupation, making the old colonial “savage wars of peace” appear by comparison as case studies for modern business schools of benign competence, has until recently served his purpose of seeming to defy the elements of chaos he himself has aroused. By stringing every threat together into an immense plot that justifies a global war on terrorism, however, he has ultimately made himself hostage to any part of the convoluted story line that goes haywire.

Because Bush has told the public that Iraq is central to the war on terror, the worse things go in Iraq, the more the public thinks the war on terror is going badly. Asked at his press conference what invading Iraq had to do with Sept. 11, Bush seemed so dumbfounded that at first he answered directly. “Nothing,” he said, before sliding into a falsely aggrieved self-defense — “except for it’s part of — and nobody has ever suggested in this administration that Saddam Hussein ordered the attack.”

Asked about sectarian violence in Iraq, Bush’s voice suddenly went passive. “You know, I hear a lot of talk about civil war.” Indeed, he might have heard it from his top generals, John Abizaid and Peter Pace, who testified before the Senate on Aug. 3, seriously off-message from Bush’s P.R. campaign of relentlessly stressing “victory.” As Abizaid said, “Sectarian violence is probably as bad as I have seen it.”

All the stopgap strategies have failed to halt it — eliminating Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, mobilizing the civil action teams, building up the police, concentrating forces in Baghdad. Asked three times what his strategy is, or whether he has a new one, Bush tried to fend off the question with words like “dreams” and “democratic society.” “That’s the strategy,” he said. Then Bush confused having a strategy with being in Iraq. “Now, if you say, are you going to change your strategic objective,” he struggled to explain, “it means you’re leaving before the mission is complete.” Finally, as always, he asserted that if the United States withdrew, “the enemy would follow us here,” forgetting that London is “here.” Or is it? “Here” dissolved into abstraction, too.

Perhaps Bush’s bizarre summer reading, according to his press office, of Albert Camus’ “The Stranger” is responsible for his mélange of absurdities, appeal to an existential threat, and erratic point of view, veering from aggressor to passive observer. Would a staff aide have the audacity to suggest that he read B.H. Liddell Hart’s military classic, “Strategy”? “Self-exhaustion in war,” wrote Liddell Hart, “has killed more States than any foreign assailant.” It was a lesson in restraint the father understood when he stopped short of Baghdad.