It is rare at this stage of a war for a president, any president, to have anything new to say to justify the loss of lives and the squandering of national treasure. The bellicose justifications grow tired whether they are built around Neville Chamberlain, the domino theory or the siren song of freedom that one day will transform the Middle East.

There is an inevitable disconnect from reality as an embattled president, any embattled president, searches for new ways to make the familiar argument that we have gone too far to retreat, that our credibility is being tested, that the chaos that we would leave behind is worse than continued carnage.

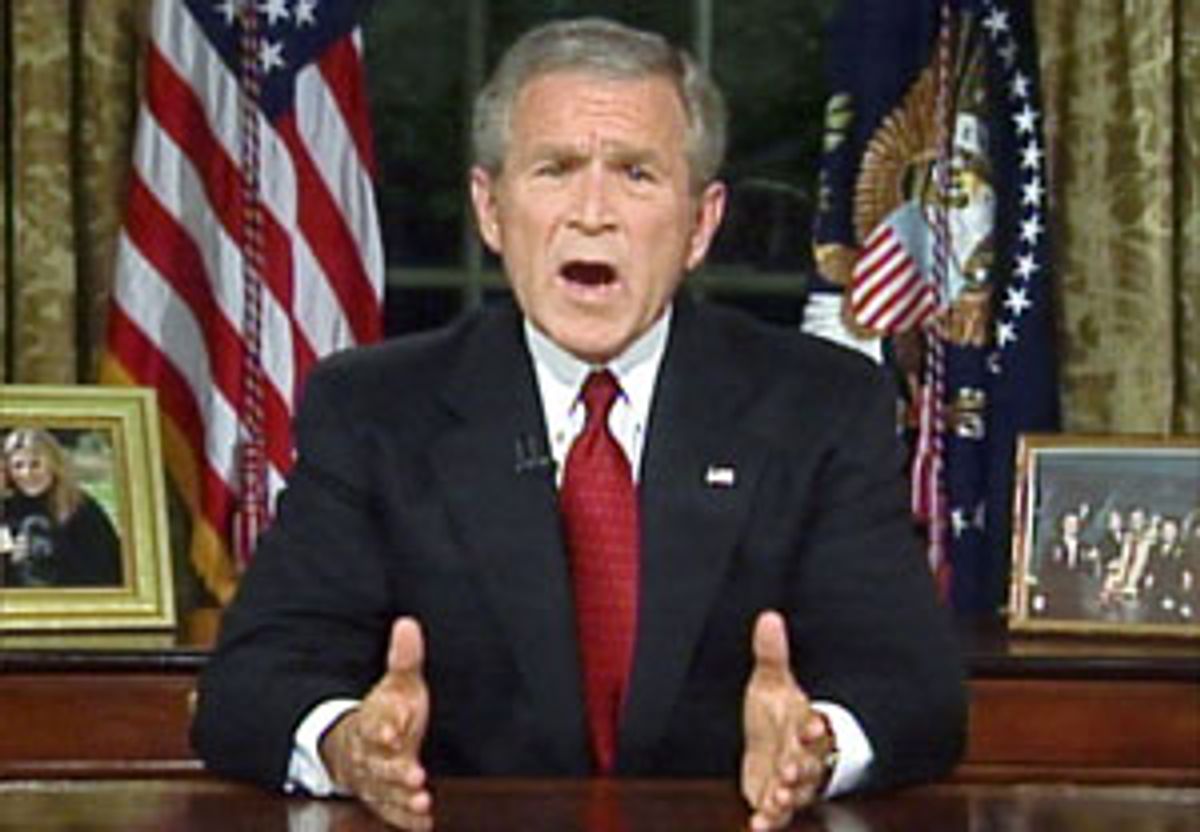

In a speech last Tuesday, at the beginning of his September offensive to justify the status quo in Iraq, George W. Bush declared, as he had so many times before, "We're determined to prevent terrorist attacks before they occur. So we're taking the fight to the enemy. The best way to protect America is to stay on the offensive."

This was the sort of rhetoric that I expected from the president's Oval Office address on Monday night. I didn't begrudge the president's right to lay claim to prime time on the anniversary of the worst day that most of us can remember. Maybe, just maybe, for one brief moment, Bush could recapture the sense of unity and community that we shared during those moments of national mourning five summers ago.

What stunned me was that instead, with just a few chilling sentences, Bush painted a portrait of war without end, amen. "The war against this enemy is more than a military conflict," Bush declared. "It is the decisive ideological struggle of the 21st century, and the calling of our generation. Our nation is being tested in a way that we have not since the start of the Cold War."

Think about that presidential prediction. Bush is saying that 50 or 60 years from now, when today's children are worried about cosmetic surgery and their retirement homes, we will still be on the battlements worldwide against an enemy whom we might call al-Qaida, the terrorists, violent Islamic radicals, the evildoers or, simply, them. This is not merely a war like Vietnam that will come to an abject end after it destroys two presidencies. No, in the Bush version of the future, a dystopian epic that might be called "It's an Awful Life," peace is a blessed oasis that might not be reached until the era of "a bridge to the 22nd century."

Equally hyperbolic is the president's claim that the nation's current struggle represents a time of testing unmatched since the days of the Berlin Blockade, the Korean War, fallout shelters and duck-and-cover drills in elementary schools. Do Bush and his advisors seriously believe that al-Qaida, scattered terrorist cells and the last-throes dead-enders in Iraq constitute a threat graver than the Cuban Missile Crisis?

Watching Bush's speech, the phrase "not since the start of the Cold War" jarred my memory. Both the White House search engine and the Nexis database led to the same place. In October 2003, just as Americans were beginning to learn how fleeting military victory in Iraq could be, Dick Cheney left his undisclosed secure location to speak to the conservatives at the Heritage Foundation.

Back then, the administration was still test-marketing new arguments to use against those nervous Nellies who worried about civil war in Iraq and those doomsters who wondered what had happened to Saddam Hussein's missing arsenal of chemical and biological weapons. "The strategy of deterrence, which served us so well during the decades of the Cold War, will no longer do," Cheney asserted in his muscular way. The vice president went on to say, as if the nation needed a reminder a little more than two years after the twin towers toppled, "There is no containing terrorists who will commit suicide for the purposes of mass slaughter."

Later in that speech, in a clear effort to equate the administration's critics with the isolationists of the 1940s, Cheney used that tell-tale analogy: "The current debate over America's national security policy is the most consequential since the early days of the Cold War and the emergence of a bipartisan commitment to face the evils of Communism."

Without being privy to the pre-speech deliberations within the White House, it is impossible to know whether Bush was consciously channeling Cheney or whether the president's ghostwriters had run out of other ways to dramatize their view of this apocalyptic century.

In writing these words, I am conscious of the dangers of Iran bristling with nuclear weapons and Iraq descending further into barbarism and religious war. We live in a dangerous world, as we have, with a few blessed interruptions, since the charnel house known as World War I opened 92 years ago.

"The calling of our generation," as Bush put it Monday night, is not total victory in the war against the jihadists. Rather it is the question of how to maintain our values, our democratic norms and our civil liberties in the face of a real, but containable, threat from 21st century terrorism.

As the president said, "We are now in the early hours of this struggle between tyranny and freedom." He was, of course, trying to fit World War II and Cold War imagery into a modern context. But Bush could have also been describing the long, twilight struggle here at home between the democratic values of Athens and the militaristic ethos of Sparta.

Shares