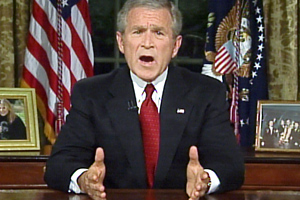

On the fifth anniversary of the Sept. 11 attacks, President Bush delivered the culmination of yet another series of speeches on Iraq and the war on terror. For more than a year, he has periodically given speeches on military bases and before specially invited audiences who applauded his carefully crafted phrases, slightly altered on each occasion, as though these scenes represented widespread public support for his policies. But this Sept. 11 was different from the other anniversaries, partly because of the passage of half a decade but mostly because of what Bush has done with the years.

Bush hoped with his latest speech to reanimate his early iconic stature in the week after the terrorist attacks, when the whole country and world were unified in sympathy. Even “evil” Syria and Iran offered assistance in tracking down al-Qaida. Bush prompted us that “the wounds of that morning are still fresh.” His evocation of emotion was an attempt to filter memory. We were guided to remember the trauma as the primal experience for sustaining Bush’s politics. By touching the source of pain he tried to redirect it into an affirmation of every twist and turn he has taken since the fateful day.

He pivoted into a peculiar rationalization for the Iraq war that was defensive and distorted — one that ultimately rested on an appeal to his own waning authority. “I’m often asked why we’re in Iraq when Saddam Hussein was not responsible for the 9/11 attacks. The answer is that the regime of Saddam Hussein was a clear threat.” But, of course, it was Bush and Dick Cheney and other prominent administration figures who had planted that impression in the public mind in the first place with thorough premeditation. Bush’s transparent effort to erase his responsibility was topped by his self-presentation as the truth teller in the matter. Just as quickly as he acknowledged the fiction that was a principal prop in the public support of the invasion, he elided over the absence of weapons of mass destruction, the other principal prop. Bush simply avoided addressing their nonexistence. Instead, he revisited his discredited justification of Saddam’s possession of WMD by restating it in the abstract without mentioning the missing WMD. They had now completely vanished. The assertion that “Saddam Hussein was a clear threat” depended not even on spectral evidence, because no evidence was introduced, only the statement of “a clear threat,” based on his insistence that it was so.

Having worked himself through 9/11 and the invasion of Iraq, he turned back to face Osama bin Laden. Bin Laden, said Bush, “calls this fight ‘the third world war’ — and he says that victory for the terrorists in Iraq will mean America’s ‘defeat and disgrace forever.'” Bush accepted bin Laden’s challenge by accepting his terms. The conflict, Bush declared, was nothing less than “a struggle for civilization.” Rather than diminish bin Laden, Bush elevated him. In so doing, he provided the incitement necessary to inflame the imagination of jihadists. Rather than explain to the American people that the ragtag terrorists are a real but not existential threat, that they should not be misconstrued as the central problem in our foreign policy, and that their presence can be coped with through confidence, fortitude and intelligence, Bush again mounted on a crusade, serving their purposes.

In the end, Bush’s speech, the product of his finest speechwriters, was as unreflective and uninformed as his expressed understanding of Albert Camus’ “The Stranger.” Bush behaves as though the world is infinitely malleable and can be made over again at his command. He waves aside the consequences of his own policies and imagines them as he wishes. He summons past conflicts — World War II, the Cold War — as though referring to them invests him with the happy ending: “victory.” He acts like a man who can speak now of “Iraq” and transform it by the adamant level of his rhetoric. But what he has done eludes his accounting.

Iraq was a dreamland for Bush and the Republicans, a utopian experiment where nearly every Republican panacea, nostrum and magic potion was applied. This utopia, administered by the Coalition Provisional Authority, employed more than 1,500 people in the Green Zone and lasted from April 2003 through June 2004. But the experiment bore little resemblance to past American utopian efforts, like the benign primitive socialist Brook Farm in Massachusetts, run by Bronson Alcott (father of Louisa May Alcott, who wrote “Little Women”), and memorialized by one of its participants, Nathaniel Hawthorne, in his novel “The Blithedale Romance.” In it, he described a “knot of dreamers” getting close to the soil. In the Green Zone, there were indeed dreamers, but mainly rogues, schemers and, above all, bunglers.

The true story of this weird American social experiment conducted between the Tigris and the Euphrates is told in a book to be published next week, “Imperial Life in the Emerald City: Inside Iraq’s Green Zone,” by Rajiv Chandrasekaran, who was the Washington Post reporter in Baghdad. There have been other books on the CPA, written by disillusioned officials, but Chandrasekaran’s offers compelling new details. His tale of innocence and pillage is recounted in a journalistic narrative of facts that speak for themselves and cut through the fog of official war rhetoric.

The Green Zone, according to Chandrasekaran, was “Baghdad’s Little America,” an insular bubble where Americans went to familiar fast-food joints, watched the latest movies, lived in air-conditioned comfort, had their laundry cleaned and pressed promptly, drove GMC Suburbans and listened to a military FM radio station, “Freedom Radio,” that played “classic rock and rah-rah messages.” Most Americans in the Green Zone wore suede combat boots. In the office of Dan Senor, the CPA press secretary, only one of his three TVs was turned on — to Fox News.

Jay Garner, a retired lieutenant general, was appointed the head of the Office of Reconstruction and Humanitarian Assistance, the precursor to the CPA. On his way to Iraq, Garner asked the neoconservative Douglas Feith, the undersecretary of defense for policy, for the planning memos and documents for postwar Iraq. Feith told him there were none. Garner was never shown the State Department’s 17 volumes of planning titled “The Future of Iraq” or the CIA’s analyses. Feith’s former law partner, Michael Mobbs, was appointed head of civil administration. Mobbs had no background in the Middle East or in civil administration. “He just cowered in his room most of the time,” one former ambassador recalled. Mobbs lasted two weeks.

Garner was “a deer in the headlights,” said Timothy Carney, a former ambassador recruited for ORHA. Feith and the neocons assumed their favorite, Ahmed Chalabi, and his exiles would seamlessly take power and the rest would be a glide path. After Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld allowed the looting of Iraqi ministries — “Freedom’s untidy,” he said — the U.S. officials supposedly building the new Iraq took weeks to survey the charred ruins. “I never knew what our plans were,” Garner said. Rumsfeld personally tried to cut every single State Department officer from Garner’s team. Soon, Garner himself fell into disfavor, and a replacement was sought. Moderate Republicans, like William Cohen, a former secretary of defense, were vetoed as being not the “right kind of Republican.” L. Paul “Jerry” Bremer III, an experienced rightward-leaning diplomat, was selected. Henry Kissinger told Colin Powell at the time that Bremer, who had worked at Kissinger Associates, was “a control freak.”

Bremer claims he argued with Rumsfeld over the failure to commit half a million troops to provide security in the country. But Bremer told Chandrasekaran on the spot, “I think we’ve got as many soldiers as we need here right now.” Feith’s office drew up an order banning members of the Baath Party, the only party permitted in Saddam Hussein’s Iraq, from holding any responsible position in government or business. Of course, those were just about the only trained personnel in Iraq, and many of them belonged to the party to hold their jobs. “You’re going to drive 50,000 Baathists underground before nightfall,” warned Garner. “Don’t do this.” Immediately after receiving Garner’s caution, Bremer announced the purge. Then Bremer disbanded the Iraqi military at the suggestion of Feith and Walter Slocombe, a consultant brought in by Feith, who had preceded Feith in his job in the Clinton administration and was now on board. Chandrasekaran asked a former soldier about the disbanded army, “What happened to everyone there? Did they join the new army?” The reply came back: “They’re all insurgents now.”

Iraq was also without police. The Bush White House sent Bernard Kerik to fix the problem. Kerik had been the New York City police commissioner during the Sept. 11 attacks, Mayor Rudy Giuliani’s sidekick. In Iraq, Kerik was uninterested in receiving briefings, according to Chandrasekaran, but gave numerous interviews to the American media proclaiming the situation to be under control and improving. He held precisely two staff meetings during his tenure. His main activity was going on nighttime raids against indeterminate targets accompanied by a shadowy former U.S. colonel and a 100-man Iraqi paramilitary force, and then sleeping most of the day. After accomplishing nothing in three months, training no police forces, he departed. “I was in my own world. I did my own thing,” he confessed.

Hiring for the CPA staff was handled by the White House liaison at the Pentagon, James O’Beirne, the husband of right-wing pundit Kate O’Beirne. He requested résumés from Republican congressional offices, activist groups and think tanks. “They had to have the right political credentials,” said Frederick Smith, the CPA’s deputy director in Washington. Senior civil servants were systematically denied positions. Applicants were questioned on their ideological loyalty and their positions on issues like abortion. A youthful contingent whose résumés had been stored in the Heritage Foundation’s computer files promptly found jobs and ran rampant in the Green Zone as the “Brat Pack.”

Bremer declared a flat tax, a constant Republican dream that Congress could never pass at home. He promulgated the wholesale privatization of state-owned industries, which created instant mass unemployment, without acknowledging any consequences. Peter McPherson, a former Reagan administration official close to Dick Cheney, was flown in to run the Iraqi economy. He stated his belief that looting was accelerating the process of privatization — “privatization that occurs sort of naturally.”

The CPA’s Carney wrote a memo to McPherson warning him that his decisions were being made “without adequate Iraqi participation,” by a “small group” in the CPA, and incidentally violated the Geneva Convention against seizing “assets of the Iraqi people.” Carney soon left the country, having served 90 days. Bremer, in any case, replaced McPherson with Thomas Foley, President Bush’s former classmate at Harvard Business School, a big Republican Party donor and a banker. Upon his arrival Foley unveiled his plan for total privatization within 30 days, writes Chandrasekaran. “Tom,” a contractor told him, “there are a couple of problems with that. The first is an international law that prevents the sale of assets by an occupation government.” “I don’t care about any of that stuff,” Bush’s pal replied. “Let’s go have a drink.” Soon Foley left, and another man with no previous experience in administering transitional economies replaced him. His name was Michael Fleischer, and he was the brother of Ari Fleischer, Bush’s press secretary.

Providing private military forces, or mercenaries, became a booming business overnight. One 33-year-old named Michael Battles, a one-time minor CIA employee and a failed Republican candidate for Congress but with political connections to the White House, partnered with a former Army Ranger named Scott Custer to form a new security firm called Custer Battles. They had no experience in the field at all. “For us the fear and disorder offered real promise,” Battles explained. Their contacts won them a lucrative contract to guard the Baghdad airport. Custer Battles became a front for an Enron-like scheme involving shell companies in the Cayman Islands and elsewhere that issued false invoices and engaged in other frauds. Though the Pentagon eventually barred the company from further work for “seriously improper conduct,” it had raked in $100 million in federal contracts.

Rumsfeld handed the first effort for political transition in Iraq to Dick Cheney’s daughter Liz Cheney, deputy assistant secretary of state for Near Eastern affairs. She had had no experience in the region beforehand. She then handed off the task to someone named Scott Carpenter, the former legislative director to Republican Sen. Rick Santorum of Pennsylvania. One disaster followed another as convoluted manipulations of the Iraqis produced frustration, chaos, sectarian friction and outbursts of violence. The CPA finally chose the leaders of the interim government, writes Chandrasekaran, “in the equivalent of a smoke-filled room.”

Bremer assigned the job of dealing with sectarian militias to his director of security, David Gompert, who had served on the elder Bush’s National Security Council. Gompert negotiated with the Kurds to demobilize their militia, called the peshmerga. In his agreement with Massoud Barzani, the Kurdish leader, to disband the militia, Gompert allowed that the Kurds would be permitted to have a brigade of “mountain rangers.” After Gompert signed the document, he asked Barzani the translation of “mountain rangers” into Kurdish. “We will call them peshmerga,” he said. No militias were disbanded.

After the invasion, there was no plan to restore electricity. The United Nations and the World Bank calculated it would cost at least $55 billion over four years for minimal investment in Iraq’s infrastructure. By the end of the CPA’s existence, only 2 percent of the $18.4 billion authorized by Congress for infrastructure, healthcare, education and clean water had been spent. However, $1.6 billion had been paid to Halliburton. One year after that, only one-third of the allocated funds had been spent on Iraq’s needs. Unemployment was at least 40 percent, electricity was on only about nine hours a day for the average Iraqi household, and $8.8 billion of Iraqi oil funds was unaccounted for.

A year after the CPA was dissolved, its veterans held a reunion in Washington. As Chandrasekaran writes, most of them had “landed at the Pentagon, the White House, the Heritage Foundation, and elsewhere in the Republican establishment, upon their return from Baghdad.” One of them, who worked for Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz, declared that in that office “the phrase ‘drinking the Kool-Aid’ was regarded as a badge of loyalty.”

To conclude the festivities, Bremer gathered his former employees around the glow of the TV set to watch President Bush deliver one in his series of speeches on Iraq, staunchly declaring that there was “significant progress in Iraq” and that the “mission in Iraq is clear.”

John Agresto, the president of St. John’s College in Santa Fe, N.M., was among the dreamers recruited for the CPA. Rumsfeld’s wife was on his board and he had worked closely with Lynne Cheney when she was chairwoman of the National Endowment for the Humanities in the Reagan administration. He came to Iraq to build a whole new university system and left having accomplished almost nothing. “I’m a neoconservative who’s been mugged by reality,” he said. But he is nearly alone among them in his shock of recognition.