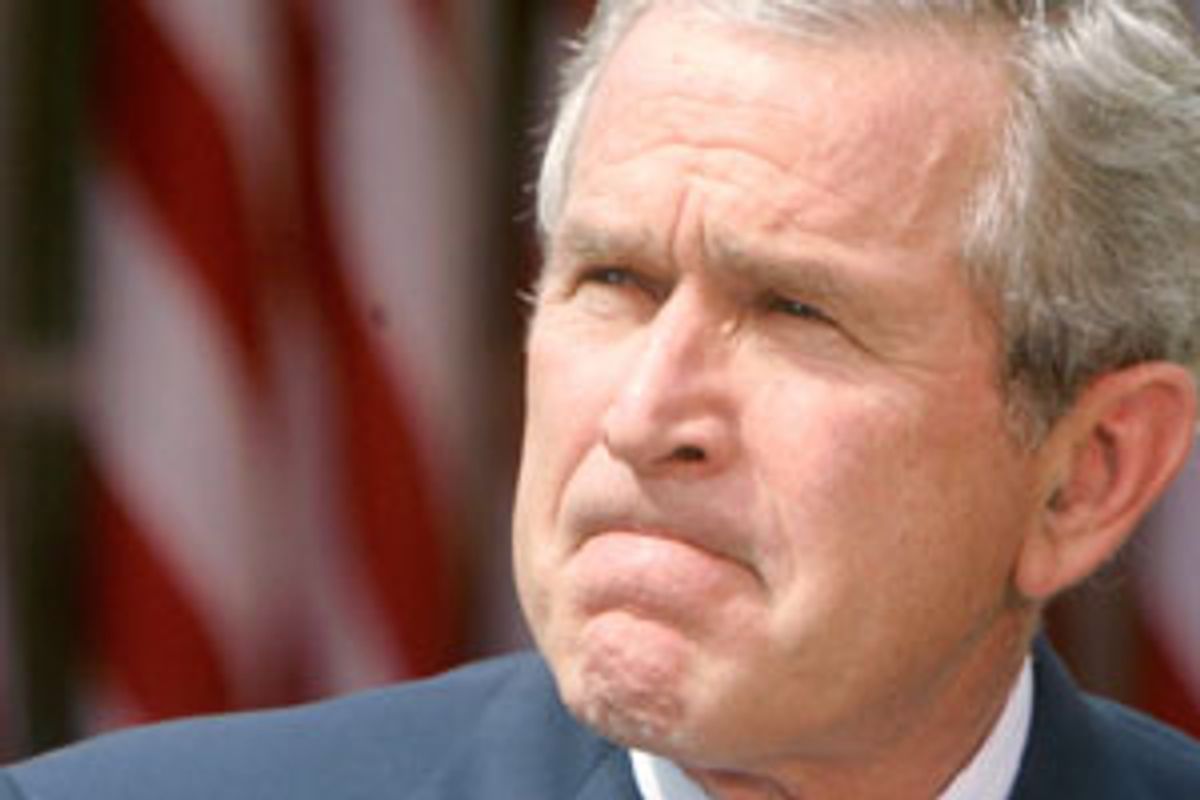

President Bush's torture policy has provoked perhaps the greatest schism between a president and the military in American history, deeper, broader and more fundamental than those of previous presidents with individual generals. Seen from the outside, this battle royal over his abrogation of the Geneva Conventions appears as a shadow war. But since the Supreme Court's ruling in Hamdan v. Rumsfeld in June, which decided that Bush's kangaroo court commissions for detainees "violate both the UCMJ [Uniform Code of Military Justice] and the four Geneva Conventions," especially Article 3 forbidding torture, the struggle has been forced more into the open.

After Hamdan, Bush could have simply allowed the Geneva Conventions to stand. Rather, he sought legislation to reinstate his commissions, permitting hearsay -- that is, uncorroborated information gathered by torture -- and denying the accused the right to know the charges brought against them, or even that they are being tried or being held for life without trial.

On Sept. 6 he made his case for torture, offering as justification the interrogation under what he called an "alternative set of procedures" of an al-Qaida operator named Abu Zubaydah. Bush claimed he was a "senior terrorist leader" who "ran a terrorist camp," had identified a member of the Hamburg cell, Ramzi bin al-Shibh, and provided accurate information about planned terrorist attacks. In fact, Zubaydah was an al-Qaida travel agent (literally, a travel agent), who did not finger al-Shibh (already known), and under torture spun wild scenarios of terrorism to gratify interrogators that proved bogus. Zubaydah, it turns out, is a psychotic with multiple personalities and the intelligence of a child. "This guy is insane, certifiable, split personality," said Dan Coleman, an FBI agent assigned to the bureau's al-Qaida task force.

Bush's argument for torture is partly based on the unstated premise that the more sadism, the more intelligence. While he referenced Zubaydah, he did not mention Jamal Ahmed al-Fadl, described by the FBI, according to the New Yorker, as "arguably the United States' most valuable informant on al Qaeda," and who is wined, dined and housed by the Federal Witness Protection Program.

On the same day that Bush made this speech, Lt. Gen. John F. Kimmons, the Army's deputy chief of staff for intelligence, presented the Army's new field manual on interrogation, which pointedly encoded the Geneva Conventions. Kimmons went out of his way to say, "No good intelligence is going to come from abusive interrogation practices."

On Sept. 15, the Senate Armed Services Committee approved an alternative to Bush's proposal, a bill affirming the Geneva Conventions, sponsored by three Republicans with a military background: John Warner, John McCain and Lindsey Graham. Former Secretary of State Colin Powell, Bush's "good soldier," released a letter denouncing Bush's version. "The world," he wrote, "is beginning to doubt the moral basis of our fight against terrorism," and Bush's bill "would add to those doubts." That sentiment was underlined in another letter signed by 38 retired generals and admirals and Powell's State Department legal counsel, William Taft IV. Retired Maj. Gen. John Batiste, former commander of the 1st Infantry Division in Iraq, appeared on CNN to scourge the administration's policy as "unlawful," "wrong" and responsible for Abu Ghraib.

Before the committee vote, the administration had tried to coerce the military's top lawyers, the judge advocates general, into signing a statement of uncritical support, which they refused to do. The Republican senators opposing Bush's torture policy had first learned about the military's profound opposition from the JAGs. For years, the administration has considered the JAGs subversive and tried to eliminate them as a separate corps and substitute neoconservative political appointees.

In the summer of 2004, Maj. Gen. Thomas J. Fiscus, the top Air Force JAG and one of the most aggressive opponents of the torture policy, privately informed senators that the administration's assertion that the JAGs backed Bush on torture was utterly false. Suspicion instantly fell upon Fiscus as the senators' source. Military investigators were assigned to comb through his e-mails and phone calls, and within weeks he was drummed out under a cloud of anonymous allegations by Pentagon officials of "improper relations" with women. The accusations and his discharge were trumpeted in the press, but his role in the torture debate remained unknown.

Bush had intended to use his post-Hamdan bill to taint Democrats, but instead he has split his own party and further antagonized the military. His standoff on torture threatens to leave no policy whatsoever -- and threatens to leave his war on terror in a twilight zone beyond the rule of law.

Shares