In 1999, at the beginning of the fourth season of "Buffy the Vampire Slayer," Buffy Summers (Sarah Michelle Gellar) -- a teenager who has been specially chosen and trained to slay the demons and vampires who walk the earth, or at least her hometown of Sunnydale, Calif. -- leaves the wholly unpredictable world of Sunnydale High School for an even greater unknown: college. She and her best friend, nerd girl-turned-Wiccan Willow Rosenberg (Alyson Hannigan), enroll at U.C. Sunnydale and move into a dorm. There, Buffy takes an immediate dislike to her roommate (she steals the girl's toenail clippings, hoping to prove she's really a demon) and engages in the universal freshman ritual of drinking way too much beer (although this brew is laced with magic juice that turns everyone who drinks it into dopey but feral Neanderthals).

"Buffy the Vampire Slayer" may have been television's most perfect, wholly rounded teenage saga. Its creator, Joss Whedon, envisioned the series as "high school as a horror movie," a feat he and his writers pulled off for three seasons without resorting to gimmickry or clichés. But maybe even more remarkable is that the show's characters survived the transition from high school to college and beyond (and Buffy's friend Xander went directly from high school into the adult work force) without losing our interest, or our empathy, in the process.

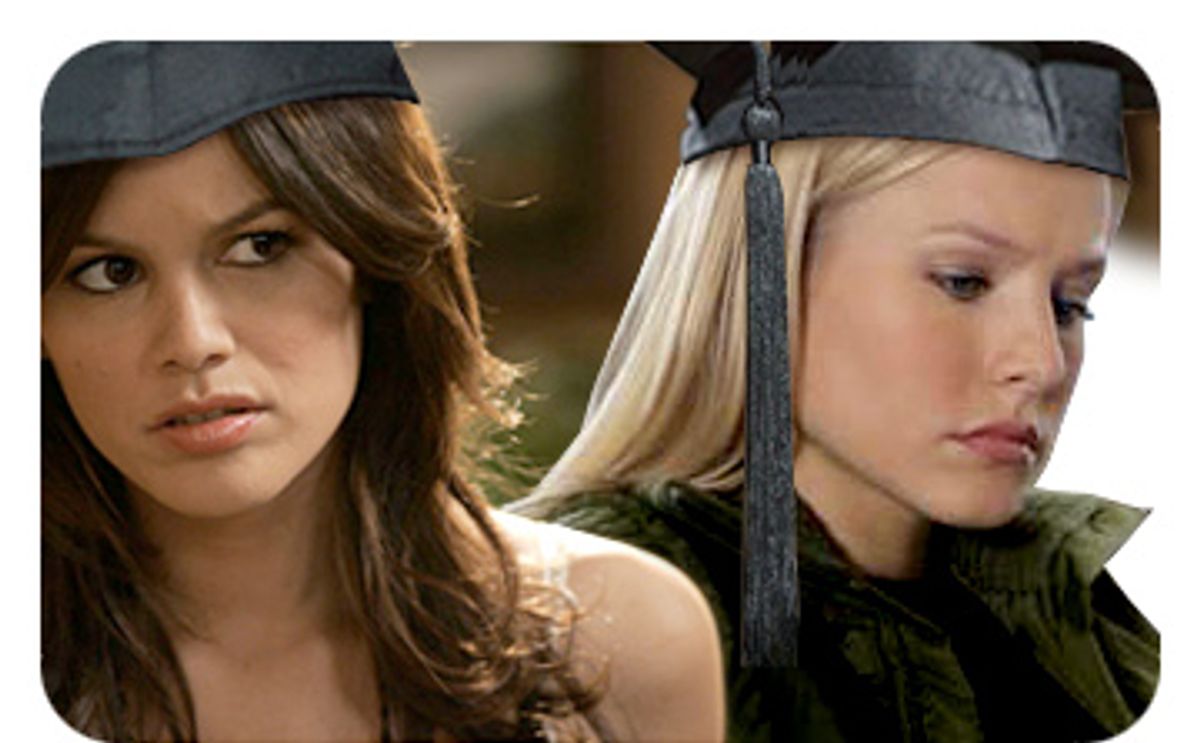

"Buffy" is a tough act to follow, but this season, two shows about teenage life proceed bravely in its footsteps: In Josh Schwartz's rich-kid teen drama "The O.C." (which has its season premiere on Nov. 2 at 9 p.m. EST on Fox), Summer Roberts (Rachel Bilson) heads off to her first semester at Brown, and the ghost of her late best friend, Marissa Cooper (Mischa Barton), seems to have followed her. And in Rob Thomas' "Veronica Mars" (which began its new season last month on the CW) teenage private investigator Veronica (Kristen Bell) has just started at the fictional Hearst College: In one of her first classes, intro to criminology, she solves a murder-mystery exercise in a matter of minutes. But she's still very much tethered to home and hearth: Instead of moving into a dorm, she continues to live with her dad, Keith (Enrico Colantoni), although there's so much trust between the two of them that her autonomy isn't much of an issue. (You get the sense that even as a toddler Veronica claimed autonomy as her birthright, and Keith Mars just knew better than to stand in her way.)

These aren't the first shows since "Buffy" to pack their protagonists off to college: The mother-daughter Chip 'n' Dale routine "Gilmore Girls" is now nattering into its seventh season, but Rory (Alexis Bledel) enrolled at Yale several seasons ago. Since then, she's stolen a yacht and taken some time off from her studies, and now she's cracking the books once again.

I've never warmed to "Gilmore Girls," now on the CW, or even been tickled by its rat-a-tat pop-culture references. (Why on earth did Norman Mailer pick that show to guest-star on? Imagine Mailer on "Buffy," doing battle with the Hellmouth -- or, better yet, showing up as one of its denizens.) Since the end of "Buffy," "The O.C." and "Veronica Mars" have been where I get my teenage fix. The two shows are wholly different from "Buffy," and from each other, in the way they look at teenage life: "The O.C." is an unapologetic soap opera, with twists and turns so dramatic they're sometimes barely convincing. But as with all good melodrama, the emotions churned up by these wild events are always completely believable. (When Marissa Cooper was killed by a jealous, psychotic ex-boyfriend on last season's finale, her death felt like both a revisitation of a deeply familiar theme and a sucker punch -- like a reworking of the 1960 weeper-hit "Teen Angel" with the maudlin gloss toned way down.)

And Veronica Mars is a teenage girl unlike any we've seen on TV, a noir heroine so self-possessed she barely fits in with the adults around her, much less kids her own age. This is a young woman who can get the job done, solving the mystery of her best friend's murder in Season 1, or tracking down the perpetrator of a deadly school-bus crash in Season 2. But as "Buffy" did before it, "Veronica Mars" explores deeper fears and anxieties of near-adulthood without belittling them -- in fact, those fears and anxieties hit adults more keenly than they do younger viewers. (My sense is that "Veronica Mars," like "Buffy" before it, attracts more adult viewers than it does teenagers.)

"Veronica Mars" doesn't have the operatic scale of "Buffy the Vampire Slayer," but it's similar in the way it refuses to trivialize teenage -- that is to say, human -- suffering. In Season 2, Veronica contracts chlamydia, enough of an annoyance by itself, except that her father finds out about it in a courtroom, where this piece of "evidence" is being used against her by scumbags; in Season 1, she lived through the experience of being drugged and raped at a party, only to learn that it was her own boyfriend, Duncan (Teddy Dunn), who did it -- and not out of malice but out of clumsily expressed love. That may not be a grand tragedy on the scale of having your boyfriend turn into a vampire after he's taken your virginity (as happened to Buffy); but as a reminder of the way human beings can't help falling short of what we expect from them, it's pretty potent.

The big question now is, can these shows' characters -- and can the writing -- survive the high school-to-college transition? College students aren't quite grown-ups, but they're getting close; by the time kids head off to college, some of that teenage awkwardness has already started to burn off. When we're out and about, on the street or in a restaurant or store, we can't help feeling a pang of sympathy for the plump 15-year-old wearing braces. But the sloppy-drunk college kid lounging around the local watering hole, flashing around his fake ID (or, worse, his legit one), is another story.

But good TV -- like good filmmaking or writing -- doesn't tell you what you already know; it points toward the gaps in everything you think you know. And so while Summer Roberts, in the first few episodes of Season 4 of "The O.C.," is settling into life at Brown, the problems she's running into aren't necessarily the ones we expect. And even the problems we do expect -- she's continuing her relationship with her boyfriend, Seth (Adam Brody), long-distance, until he joins her at Brown in January -- have unexpected angles.

Summer, as we learn in the season opener, has befriended a tree-hugging activist named Che (the strangely endearing Chris Pratt), the kind of guy who accessorizes his slogan-riddled T-shirts with crocheted rasta hats and beaded necklaces. In other words, she's made friends with a cliché, a sly joke the show winkingly acknowledges, because college is the very place to try clichés on for size. But even if we can't fully buy -- or even like -- a Summer who has traded Marc Jacobs for Birkenstocks, this sudden (and possibly not long-lasting) transformation makes more than a few glints of sense: Earlier in the show's history, we were made to assume Summer was just a bubblehead -- until, it turned out, her SAT scores flew off the charts (they were much higher than Seth's). It's more comfortable for us to think of a girl like Summer, who cares mostly about gossip rags and spending money at the mall, as a flake; that way, we can feel superior to her. And then suddenly, we (and Seth) had to reckon with the fact that this seemingly shallow young woman has more innate intelligence than many people who work hard at being smart.

I suspect people who have never gotten "The O.C.," and even some people who have, might roll their eyes at this revelation, unable to buy it as credible. But I think many of us have known people like Summer Roberts -- she's the quiet young woman at a dinner party who, when she finally speaks up, says something infinitely smarter than anything the guy blowhards around the table have been able to come up with in hours of pontificating. The revelation of the major coconut on Summer's shoulders is the show's way of tweaking us, of reminding us how little we actually know about people (even TV characters) we think we've got all figured out.

Back in her affluent corner of California, Summer had no trouble reconciling her intelligence with her frivolity because she never had cause to question it. Now, at Brown (also an insular world, but at least a different insular world), she's starting to find out how much she doesn't know about how the world works. On the one hand, it's absurd to think of Summer sleeping outdoors to protest the destruction of a tree. On the other hand, it's not so weird to think of her making a cogent case, at a student-body meeting, for the installation of solar panels at the school. The cliché of college is that it's where you begin to figure out who you are. The finer distinction beyond the cliché is that, ideally, college is the place where you learn how to use what you've got.

Summer is changing, as all kids who go away to college do; she's also growing distant from Seth, for reasons that are both obvious and yet not completely clear -- which is so often, terrifyingly, the way relationships crumble in real, adult life. And the show is still very much rooted in California, because Summer is the only one of its characters who has left it: Seth is waiting to start college himself, working in a comic-book store. But he does have the burden of worrying about Ryan, who has never quite tamed his tendency toward hotheadedness, and who's now out to avenge the murder of Marissa, his girlfriend. Seth needs to enlist the help of his parents, Kirsten and Sandy (played by Kelly Rowan and the wonderful Peter Gallagher), which makes him feel ashamed -- more like a little-kid tattletale than a mature adult.

Seth is in suspended animation, while Summer is poised for takeoff. In "Veronica Mars," Veronica hasn't left home, either in the literal or figurative sense. She's still very close to her dad: One mark of both of these shows, an extension of ideas Whedon riffed on in "Buffy," is that the parents aren't just afterthoughts. They may be outsiders in the teenage world (they have to be), but they're not villains. Keith Mars may trust his daughter, but the protective-parent mechanism isn't something he can just turn off: He winces when he has to be away from home for a night and recognizes that he can't, and shouldn't, try to stop her from sleeping with her boyfriend, Logan (Jason Dohring).

And while Veronica may have found the class demarcations constraining, or at least annoying, at Neptune High, at Hearst College she's having to deal with different kinds of hierarchies. There's a serial rapist at the school (a plot point that was introduced last season); he shaves the heads of his victims, a particularly arrogant way of leaving his mark on them, and one that's obviously designed to make them feel shame over a crime that's been committed against them.

Veronica wants, of course, to find out who the rapist is, and at one point, she's hired by a fraternity to prove that the rapist hasn't come from their house. But the harder she tries to figure out the identity of this twisted creep, the more elusive he (she?) becomes. Veronica -- a private detective, it seems, not just by profession but also by nature -- is trained to see what's really there, instead of just what's convenient or easy. And so the view of college life in "Veronica Mars" doesn't fit onto the usual grid: Frat boys aren't necessarily the pigs we'd like to write them off as. The kids who work for the student newspaper aren't heroes, but wily types who are using journalistic privilege for their own questionable purposes. (What those purposes are, exactly, we don't yet know.)

And while Veronica is visibly annoyed by the rigid self-righteousness of the campus Take Back the Night activists, she also can't deny that the problem to be dealt with here is grave. The show acknowledges, with a suitable degree of caution and tentativeness, that college sex (or, more accurately, any sex) often involves gray areas -- moments in which one person believes consent was given, while the other remembers a firm, clear "no." None of this is foreign to Veronica, given her own experience. And she's stricken when she learns she could have stopped what she later learned was a rape in progress. Entering a dorm room, Veronica accidentally walks in on two people having what she assumes is consensual sex -- partly because that's the sort of thing that goes on at college, but also because she has met the woman briefly and has pretty much summed her up as a flirt and a partyer. In other words, Veronica suddenly becomes aware that her assumptions -- and sometimes it's difficult to discern assumptions from observation -- may have stopped her from taking action.

Veronica may be brilliant, but she's not infallible -- no great television character, with the possible exception of Superman, ever is. The unfortunate reality, though, is that we may have "Veronica Mars" for only one more season.

Both it and "The O.C." are suffering from a lack of confidence on the part of the networks that air them -- respectively, the CW (formerly the WB) and Fox. Sixteen episodes of "The O.C." have been ordered for the season; "Veronica Mars" has only 13. That's barely enough time for these characters to gain, let alone lose, their freshman 15.

It's possible that "The O.C.," at least, may be rounding the curve toward its natural end: The first of the new season's episodes is unsettling and somber, pointing ahead, maybe, to a day when we'll have to say goodbye, and not just for the summer, to these characters we've come to care about. There's honor in bringing a series to a close at the proper time. But if this season marks the end of "Veronica Mars," that will simply be a case of a great show being stricken in mid-stride. For Veronica, college is proving to be more challenging than high school was; if there's any sort of benevolent god in the TV world (and I'm not sure there is), we'll get to follow her through until she lands that sheepskin. If not, we'll just have to face a hard, adult reality grown out of a classic teen lament: Breaking up is hard to do. And it only gets harder as you get older.

Shares