For the past month, while the national political conversation has concerned itself with racy military thrillers and antique racial slurs, the real issues -- the big, soul-scraping ones -- have been wrestled with in the wasteland of Friday night basic cable programming, on a channel otherwise devoted to no-budget thrillers about killer centipedes.

Surely you've heard by now (because we've certainly repeated it often enough) that "Battlestar Galactica," the new remake of the cheesy '70s series, is the most thrilling and trenchant dramatic series on TV at the moment (except, of course, for "The Wire"). Maybe you still haven't given it a shot because you just can't believe a show set on a spaceship could possibly engage you when you can watch the simpering narcissists of "Grey's Anatomy" instead -- in which case, you are an idiot. But if you've simply not yet gotten around to it, hurry: Rent the DVDs of Seasons 1 and 2 (they're short), and then hasten over to iTunes to catch up on the first handful of episodes for Season 3 because this one is not just about other planets; it's about our own.

The first season of "Battlestar" seemed daring merely for having the remnants of the human race persecuted by a genocidal, sanctimonious and devious enemy, the Cylons, who were not above sending suicide bombers onto the humans' ships. The series' troubled fighter pilot heroine, Starbuck, showed her darkest side when she was put in charge of interrogating a Cylon captive and tortured him without a tinge of conscience. (The Cylons, a kind of robot created by robots that were originally created by humans, are nearly indistinguishable from human beings, even under close scrutiny. The humans' position is that they're "toasters," and homicidal ones at that, but it's not always possible to maintain this position, as the story of the Cylon Sharon has demonstrated.)

At the end of Season 2, however, the show's creators executed a daredevil twist by scooping most of the characters (along with the remaining human population) off their ships and onto a dreary colony on a planet they called New Caprica. At the very end of the season finale, an overwhelming Cylon force descended, marching through the muddy streets of the tent city, and announced that they were taking over. Instead of trying to exterminate humanity, they were going to try to reform it. And the chosen method of reform would be a little thing we call occupation.

The two opening hours of Season 3 were, it must be said, unrelentingly grim. The humans, shivering in damp bulky sweaters and fingerless gloves, had mounted an insurrection. Gaius Baltar, the self-serving scientist and secret Cylon collaborator whom they had rashly elected president, was running a Vichy-like government that had become hopelessly implicated in the Cylon's brutal crackdowns on the rebels. Colonel Tigh, the former executive officer of Galactica, a leader of the resistance, lost his eye while being detained and interrogated, like many others, without charge or due process.

Some colonists, whether out of a misguided attempt to ameliorate the situation or out of bald self-interest, had signed on with the human police force that the Cylons set up to maintain order. They had to keep their identities secret, however, because the insurrection regarded them as collaborators. The Cylons just couldn't understand why the humans wouldn't behave. The humans just wanted the Cylons to go away.

The parallels to current events are obvious, but "Battlestar Galactica" has always kept more than one historical touchstone in play. The early scenes, when Secretary of Education Laura Roslin was sworn in as president because everyone above her in the civilian line of command had been massacred, cited the swearing in of LBJ after the Kennedy assassination. The scene of the shiny, terrifying Cylon centurions (a servant class of robots that actually look like robots) marching down the main road of New Caprica while the devastated colonists looked on was the Nazis marching into Paris.

The really audacious stroke of this season was showing us a story about a suicide bomber from the point of view of the bomber and his comrades -- no, it was more than that, because the cause of this terrorist was unquestioningly our own. We sympathize with the insurgents wholeheartedly. So when Colonel Tigh, a blood 'n' guts military man if there ever was one, insists that suicide bombing is the only way to end the occupation, the show leaves the question of whether he's right up to us. Is it worth it?

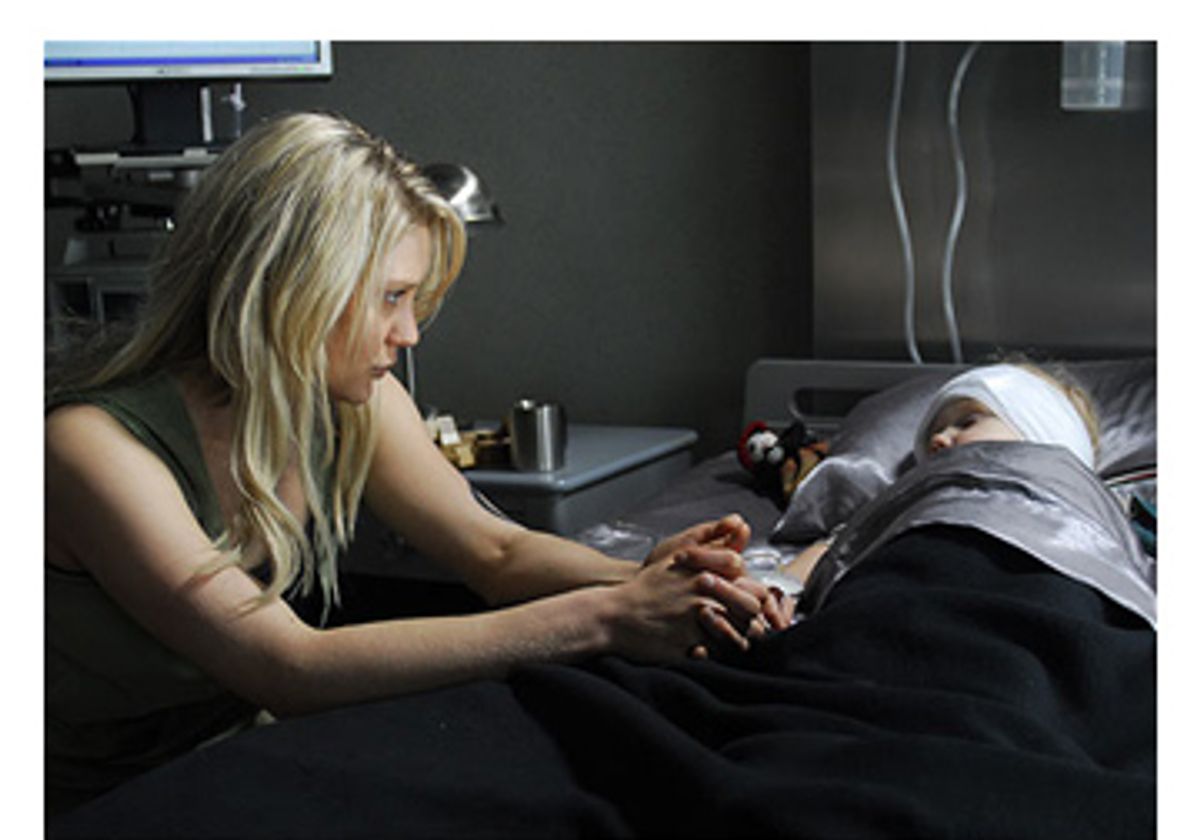

The humans in "Battlestar" don't have an overarching religious fanaticism to persuade them that it is. (The Cylons are the messianic monotheists.) So when Baltar confronts former President Roslin in her jail cell about the morality of the suicide bombing, and demands that she look him in the eye and tell him it's the right thing to do, she can't. Every time you start to get all starry-eyed and latch onto Roslin as the second coming of Josiah Bartlet, the show reminds you that it's a whole lot tougher -- on its characters and its viewers -- than "The West Wing" was. "Battlestar Galactica" may be set in outer space, with robots, in the far distant past, but it reminds us every week that the other TV shows are the fantasies. "This," as Roslin tells her stricken assistant in a recent episode, "this is life."

Shares