When I was a kid, growing up in Berkeley, San Francisco's North Beach seemed as old, sinful and mysteriously hip as a daguerreotype of a 19th century stripper. I might have driven through it once or twice with my parents, and my memories are a blur, the gaudy lights of adjoining Chinatown, the scary strip joints on Broadway, the cafes reeking of espresso and vanished Beats, and the indefinable Italian-ness of it all combining to make up something that felt less like a neighborhood than a dream.

Eventually I realized my dream and moved there, but I still felt like I was wandering around in a place more grown-up than me, and more fabled than I deserved. The whole life history of San Francisco was in its streets, from its roistering Gold Rush start to Mark Twain's wild newspaperman days to Kerouac and the jug-guzzling, chanting Beats. It was seedy and glorious. Broadway looked like Times Square at night, all glowing lights and glory, and in the day turned into a 25-buck whore with her makeup peeling off. City Lights was the church of literary revolution, and I'd see Allen Ginsberg and even the reclusive Bob Kaufman walking down upper Grant. Jazz wafted from little clubs. Unclassifiable post-Beat hipsters, not hippies or eggheads or anything else recognizable, wandered its byways. The Beach was vaguely decrepit, already past its glory days, but its mephitic vibe made it even cooler. It was a neighborhood of beautiful losers in a city that specialized in that.

North Beach was the heart of the city I inherited and first loved. I didn't think it would ever lose its aura: it would forever be frozen in amber, like Baudelaire's Paris. But it changed, or I did.

Cities are archaeological digs, and the layers are made up not just of decaying objects but of memory. As I walk through North Beach today, I walk through a place as resigned, well-behaved and familiar as I am. All the years I spent looking at it with completely different eyes, with the wild surmise of youth, are gone.

But sometimes, turning a corner onto a certain alley, I remember.

My memories are, alas, erratic. One drunken evening was so much like another, around the corner of that green and neon dreamland that has vanished now except for the flashing nipples that sometimes blink at me a moment before sleep, that I can never remember if I chugged a 48-ounce when I was 32 or chugged a 32-ounce when I was 48. All the North Beach stories stagger down to the cross-eyed shitfaced sea, and I put in my hand and bring out whatever I can find. And I pull out my gray tweed jacket and the unextinguished joint.

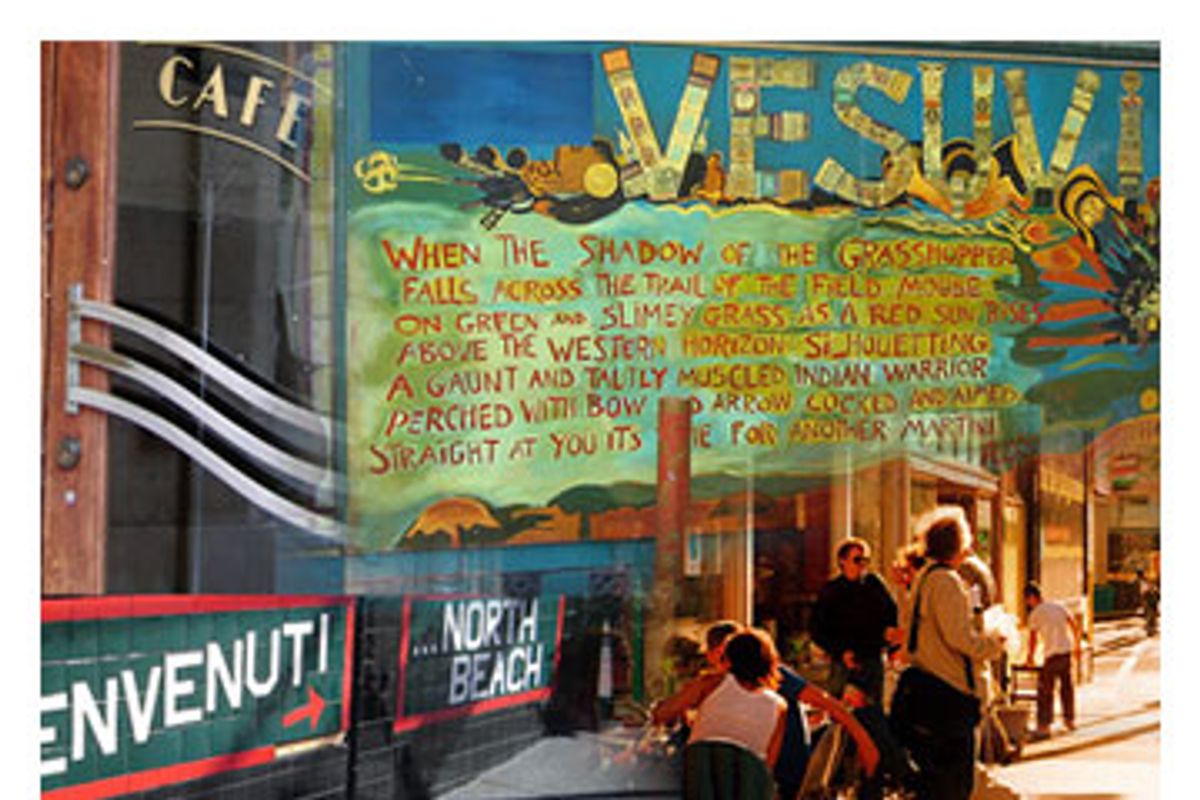

I was walking one night from Nob Hill down Pacific Avenue to North Beach. My destination that night was not Vesuvio, or Tosca, or the Caffe Italia, or Keystone Korner, or Frank's Extra, or Gulliver's, or the Saloon, or Mooney's Irish Pub, or Grassland, or the Lusty Lady (honesty compels me to surreptitiously drop that name like a greasy quarter into the dead center of this Homeric list of watering holes), or the Portofino, or Spec's, or Silhouette's, or the North End, or Tony Nik's, or the Columbus Cafe, or Gino and Carlo's, or the Old Spaghetti Factory, or La Bodega. No, it was, of all things, a theater. I was going to a play -- one of the few times I ever imbibed anything remotely resembling High Culture in North Beach.

This play, a piece of British frippery called "Bullshot Crummond," was being performed in a theater that briefly and unsuccessfully occupied Carol Doda's old strip club, the Condor. Beyond being the Ur-fake-titty bar, the Condor was famous as the place where a bouncer screwing a dancer was crushed to death by a piano. The piano was fitted with a hydraulic lift that raised it slowly to the ceiling. After mounting the dancer, the aforementioned bouncer accidentally kicked the start lever. Distracted by the throes of passion, he failed to realize that his love was literally, to quote the immortal words of Jackie Wilson, lifting him higher. He was crushed slowly and inexorably against the ceiling and died. Cushioned by his expiring body, the stripper survived.

It was a sad and instructive tale, and one that should have made the rogues of North Beach change their lecherous ways. Yet so sunk in vice were the Beach's habitues that the only discernible effect it had on male behavior was that for months afterward, a near-total aversion to the missionary position was reported throughout the neighborhood.

But such grim thoughts were far from my mind as, like Toad in "The Wind in the Willows," and about to meet the same humiliating fate, I went a-pleasuring gaily down the street. In my pocket was cash, in my young heart was frivolity and in my hand was a burning joint, which I partook of freely as I strolled down Pacific. Arriving at the theater in fine spirits, I casually crushed out the joint with my fingers and placed the roach in the pocket of my gray herringbone jacket -- for years one of my favorite coats, a respectable-looking number that I had picked up from a free box in the city's Noe Valley. With the suave demeanor of a boulevardier, I paid for my ticket and entered the theater. I looked around for a seat. The place was almost full. It was dinner-theater-style seating, people jammed close together around cafe tables. I found a seat in the midst of a group of people right near the stage. The play was just starting. With the aplomb of a man of the world I sat back and watched the action unfold.

The actors cavorted, the audience laughed. A warm and intimate feeling suffused the room, a sense of easiness and comfort. Then I became dimly aware of a peculiar smell. I paid it no heed. The play continued. Bulldog Drummond ambled across the stage. The audience laughed. The smell became slightly stronger. I ignored it. Men of sophistication do not look down. The play went on.

The female lead made her entrance. Now the burning smell seemed to be coming up from directly below my seat. Was it some sort of special effect? An undeniable cloud of smoke was wafting in my face. I looked down. To my horror, I saw that a plume of acrid smoke was pouring out of the pocket of my gray herringbone jacket, rising into the air like an innocent campfire. The smoke was now thick and the smell noticeable and unpleasant -- eau d' wool jacket, with just a hint of cheap weed. The people sitting around me turned and looked at the smoking coat and then at me. I sensed confusion and disapproval -- even, God help us, the beginning glimmers of a fatal knowledge. Soon the firemen would come, and the police, and Mrs. Prothero, and I would be taken away in handcuffs.

I hastily smothered the fire, burning my hand in the process. The bad-smelling smoke hung in the air for a few moments like a humiliating fart whose origin cannot be plausibly denied. After it dissipated I tried to resume my former debonair pose, but it was no good. I was no longer a man of the world. I had been exposed to all of Paris, or at least to the theater-goers of North Beach, as a buffoon who had ignited his coat with a still-burning roach.

But youth is nothing if not resilient. Like the irrepressible Toad, my role model at that point in life, I popped up from that humiliation to once again try my luck. And so I found myself one evening in some now-vanished bar at Broadway and Montgomery, listening to a jazz trio and eyeing an attractive woman.

The woman had a very strange demeanor. She was sprawled loosely and aggressively across a seat and had an expression I've never seen before -- lordly and vaguely extraterrestrial. Naturally, I immediately began chatting her up. Her responses were smart but slightly out of focus, like she was trying to hear something far away. After a few minutes I asked her if she wanted to get a coffee. She looked at me quizzically for a moment; it was like she was trying to figure out if I was hip enough to understand what she was going to tell me. "I can't go," she said. Then, with an odd, knowing little smile, she confided, "You see, I don't live in this reality."

I'd heard "I have a boyfriend" and "I'm too busy" and "Get lost, creep," and dozens of other rejections before, but this was a new one.

"Oh, I come down here," she explained, a sly glint in her eye. "I enjoy the show, go on all the rides -- I have an e-ticket. But then I have to go back up." As she spoke, I had the distinct and scary impression that she actually knew she was insane, but preferred being up there.

"So I guess this means you don't want to have a cup of coffee," I said.

Time went on and even Mr. Toad grew up -- sort of. I learned to avoid schizophrenic hotties and stopped putting out joints in my coat pockets. But I kept going to North Beach.

My dear old friend Jack Lind was the most boho dude I ever knew. He was a Danish jazz aficionado and former newspaperman who when I met him was living on a houseboat on Gate Five in Sausalito. Later he followed my footsteps into taxi driving, which he loved and which he kept doing long after all of us had gotten out of the gig. There's still a picture of him on the wall in Vesuvio, with a bunch of other taxi drivers, writers and drunks. He was a free spirit and a great, lovely man. I can still hear him snapping his fingers to Dexter Gordon, hear his deep voice saying, "You want to get a horn, man? You know, a little drinkie-poo?" He embodied what Jack Kerouac said about San Francisco -- "It was the end of the continent; they didn't give a damn." He was a lot older than I and he passed away of cancer eight or 10 years ago in Copenhagen, his native town.

When he died, his old friends, most of us by now married, with kids and jobs and mortgages and private school tuitions, all met in North Beach, scene of so many of our past escapades with Jack, to have a wake for him. We had a drink at Vesuvio, or maybe it was Spec's, and told each other stories about him. And we had to do it right, so we went out and walked a block up Romolo Alley, one of the great little alleys of North Beach that runs north off Broadway, and went past Fresno, another fabled alley that runs past the Saloon, which used to be the neighborhood jail in the 19th century before becoming a supremely raunchy blues bar. We chose this corner because it was surreal and deep and utterly urban and a secluded place to hoist a drink in Jack's memory.

There is one block of Romolo that is the most insanely ungraded street in San Francisco -- it has a hump that tilts off to the side so crazily that your car could almost tip over driving up it. There is an old parking lot across the way and as you sit on the curb at this little hidden four-way corner you're surrounded by the worn-out gray back ends of apartment houses, as the big buildings of downtown rise up in the distance. It's one of North Beach's sacred lost corners, places where romance and memory and loss are soaked into the cobblestones. That's where we said goodbye to Jack, and to a vanished time in our lives, of kicks and foolishness and dreams.

But North Beach follows you around. You don't lose it. It gets old with you. And the lines you see in its face, the cracks in its mythical façade, are just as beautiful as its dawn.

On the northern boundary of North Beach, at Chestnut and Columbus, stands a joint called LaRocca's Corner. La Rocca's Corner's claim to fame is its venerable neon sign, which proclaims, "This is It!" I have had a few horns in LaRocca's, and by every standard, this is the falsest advertising in town. But if you stick around 60 or 70 years, if your bar has an autographed photograph of Rocky Graziano on the wall, even the stupidest kitsch turns to hammered Byzantine gold.

Actually, that's the dirty little secret of the whole neighborhood, from the Barbary Coast days through the International Settlement, the Beats, the hippies, the brief and scary yuppie era, the dot-com Dieters with their Auschwitz haircuts and now the nameless refugees from GeorgeBushLand. The dirty secret is that there never was a Golden Age. North Beach has been dining out on its myth forever. We're nostalgic for Jack Kerouac? Well, guess what -- Jack Kerouac was nostalgic for Jack London, and Jack London was envious of Robert Louis Stevenson, and Robert Louis Stevenson thought that Mark Twain got there first and ate all the candy, and Mark Twain -- he just wanted to be back on the Mississippi. The first Chilean who stumbled up Telegraph Hill and nailed a plank on Alta Street 150 years ago sat there looking out over the Bay and said to himself, "This Is It!" in big mental neon letters, and we've all been reciting that same smug mantra, the slogan of the Alan Watts Realty, ever since.

We know the pot of gold is bogus, but we still keep going there. We've been doing it for years -- as young men, not so young men and now not young men at all. We keep heading to North Beach, keep turning left on Churchill Alley out of the Broadway tunnel, even though in those 30 years we have never yet once hit the jackpot, felt the supreme high, made the scene, danced the dance, met the chick, seen the best minds of our generation doing anything, let alone walking through the Negro streets at dawn looking for an angry fix.

But it doesn't matter. There's always next time. And when you finally begin to understand that there ain't going to be no next time, that this is it, that's OK. You don't need North Beach to give up its secrets because you know them all. Because you're on the corner of Grant and Green in this sad old Italian valley beneath its two guardian hills looking down like kindly old paisans, and the waves are lapping down at Aquatic Park to the north and the filthy numberless alleys of Chinatown lurk to the south, and the glasses in every bar are full and Broadway is stupid jammed with John Dos Passos sailors and the Palmistry sign is reflected in the upper windows of Vesuvio and the parrots are flying above Washington Square and the Mason Street cable car rattle-clatters onto Columbus and you're at the dead center of town, the bull's-eye, where you've been a thousand times before and where you will always return, where you left your heart, and where you found it.

Shares