The last time Robert M. Gates saw his nation trapped in an unwinnable war, he was just 23 years old, working as a CIA-sponsored intelligence officer on a ballistic missile base in Missouri. The year was 1967, and President Lyndon Johnson was still telling America to "firmly pursue our present course" in Vietnam. "General Westmoreland reports that the enemy can no longer succeed on the battlefield," Johnson announced in his State of the Union Address that year. "So I must say to you that our pressure must be sustained."

But Gates knew better. Though he was just a couple of years out of college, he had watched as aging Air Force pilots were shipped off to Southeast Asia to replace their fallen comrades. "I caught a glimpse of the impact of the Vietnam War on America's overall strategic strength, and it was depressing," Gates wrote in his 1996 memoir, "From the Shadows." "We knew then we would not win the war."

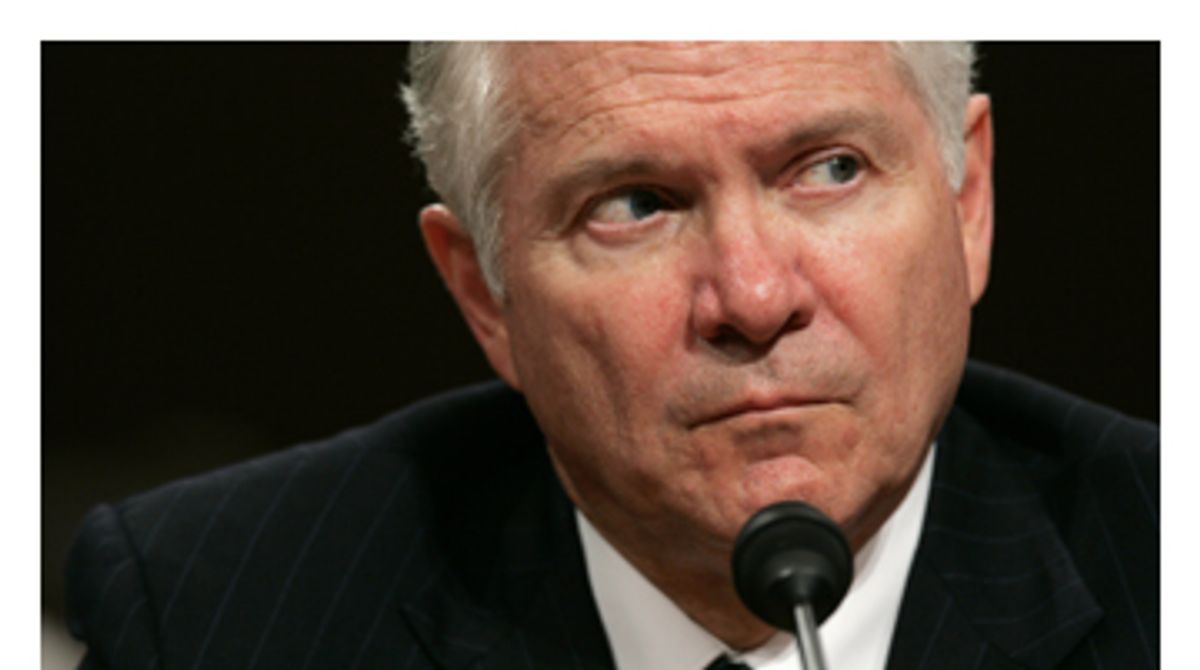

On Tuesday, nearly 40 years later, Gates found himself seated before the Senate Armed Services Committee, faced with a new military quagmire and the chance to serve another president whose upbeat assessments of military progress have been called into question. No longer a CIA cub, he was there to apply for the top job at the Pentagon, hoping to become the man responsible for bringing U.S. troops home from a war gone wrong while avoiding the stigma of defeat. "We need to work together to develop a strategy that does not leave Iraq in chaos," he told the gathered senators. "I am open to a wide range of ideas and proposals."

The committee's ranking Democrat, Sen. Carl Levin of Michigan, cut straight to the chase. "Mr. Gates, do you believe that we are currently winning in Iraq?" Levin asked.

"No, sir."

Gates later clarified his response, saying he also did not think we were currently losing in Iraq or that the military had failed on the battlefield. But his die had been cast, and his career had come full circle. As the reporters left the room to file their stories, the headline was already written for them. Gates was establishing himself as the antipode of Donald Rumsfeld, the current secretary of defense, whose loquacious refusal to accept the obvious long ago turned him into a political scapegrace. Gates had also gone toe-to-toe with President Bush. "Absolutely, we're winning," the president announced at an Oct. 25 press conference.

As the un-Rummy, Gates was greeted with open arms by Democrats and Republicans alike, who have been hungering for someone who can point to a clear sky and call it blue. When asked if Iraq was the "central battlefront in the 'war on terror,'" Gates again departed from the White House line. "I think it is one of the central fronts," he answered, after a pause, pointing out his concerns with the recent deterioration of conditions in Afghanistan. When asked what mistakes had been made in Iraq, he was again blunt -- not enough prewar understanding of the deterioration of Iraqi infrastructure, the unwise disbanding of the Iraqi army, and the tragic policy of firing former members of Saddam Hussein's ruling party. When asked about Rumsfeld's creation of a separate intelligence operation outside the established channels to analyze rumors of Iraq's weapons of mass destruction, Gates said simply, "I have a problem with that." Gates was peppered with questions but remained uncommitted, saying he would have to first learn more by talking to commanders on the ground, but that he was open to discussing end-strength increases in the size of the Army and Marines.

By the lunch break, Levin was gushing. "What we heard this morning was a welcome breath of honest, candid realism about the situation in Iraq," he told a scrum of reporters outside the committee room. Indeed, it appeared as if Gates had succeeded in not offending anyone. He was agreeable when Sens. John Thune, R-S.D., and Jim Talent, R-Mo., asked if he would support bigger Pentagon budgets. He worried aloud about the dangers of invading Iran, when prompted by a question from Sen. Robert Byrd, D-W.Va., who has vigorously opposed the Iraq war. He told Sen. Joseph Lieberman, I-Conn., that it was important to forge a bipartisan consensus on Iraq. He even agreed with Sen. Susan Collins, R-Maine, that the inspector general for Iraq reconstruction should be given another term. After a classified meeting with the senators late in the day, the committee unanimously endorsed Gates to the full Senate, which will likely vote to approve his nomination this week.

That is the easy part. The task of actually finding a way out of Iraq is far more daunting, even for someone with Gates' experience as a bureaucratic climber, most recently as the president of Texas A&M University. Born in Kansas, raised as an Eagle Scout and trained as an undercover CIA agent, Gates has already worked for six presidents and served in the National Security Council of Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford, Jimmy Carter and the first George Bush. He was the deputy director and the director of the CIA, finding himself tied up along the way by both the Iran-Contra scandal and the CIA's embarrassing misjudgment of Soviet military strength before the end of the Cold War. He faced perfunctory questioning about both.

"I was, during the remarkable events from the late 1960s to the early 1990s, there in the shadows, the proverbial fly on the wall in the most secret councils of government," Gates wrote in his memoir. But even a century of experience would not adequately prepare him for the situation he will inherit. In the coming weeks, both the Pentagon and the Iraq Study Group, a congressional body to which Gates once belonged, will offer proposed solutions to the Iraq problem, though no one expects a silver bullet. "It's my impression, frankly, that there are no new ideas on Iraq," Gates said at one point in the hearing, his American flag cuff links showing from beneath a featureless dark suit. "The list of tactics, the list of strategies, the list of approaches is pretty much out there." He said he only hoped to find the right combination of existing ideas to best meet American goals. "The United States is going to have to have some presence in Iraq for a long time," he said.

At no point during the day did any senator ask Gates if he saw the ironic parallels between his former life as an opponent of the Vietnam War and his coming task of ending the Iraq war. No one asked him to recount May 9, 1970, when Gates, then a CIA analyst of the Soviet Union, joined roughly 100,000 other antiwar protesters to march on the National Mall in objection to Nixon's incursion into Cambodia.

But Gates still tried to make it clear that he knew why he was taking the job. "The pressures of this hearing are nothing compared to the pressures I got from the woman who came over to me at the hotel while I was having dinner the other night, seated by myself," he said. "She said, 'I have two sons in Iraq. For God's sake, bring them home safe. And we'll be praying for you.' Now that's real pressure.

"I can assure you," he continued. "I don't owe anybody anything. I have come back here to do the best I can, for the men and women in uniform, and for the country in terms of these difficult problems that we face."

His country must now hope that his best is good enough.

Shares