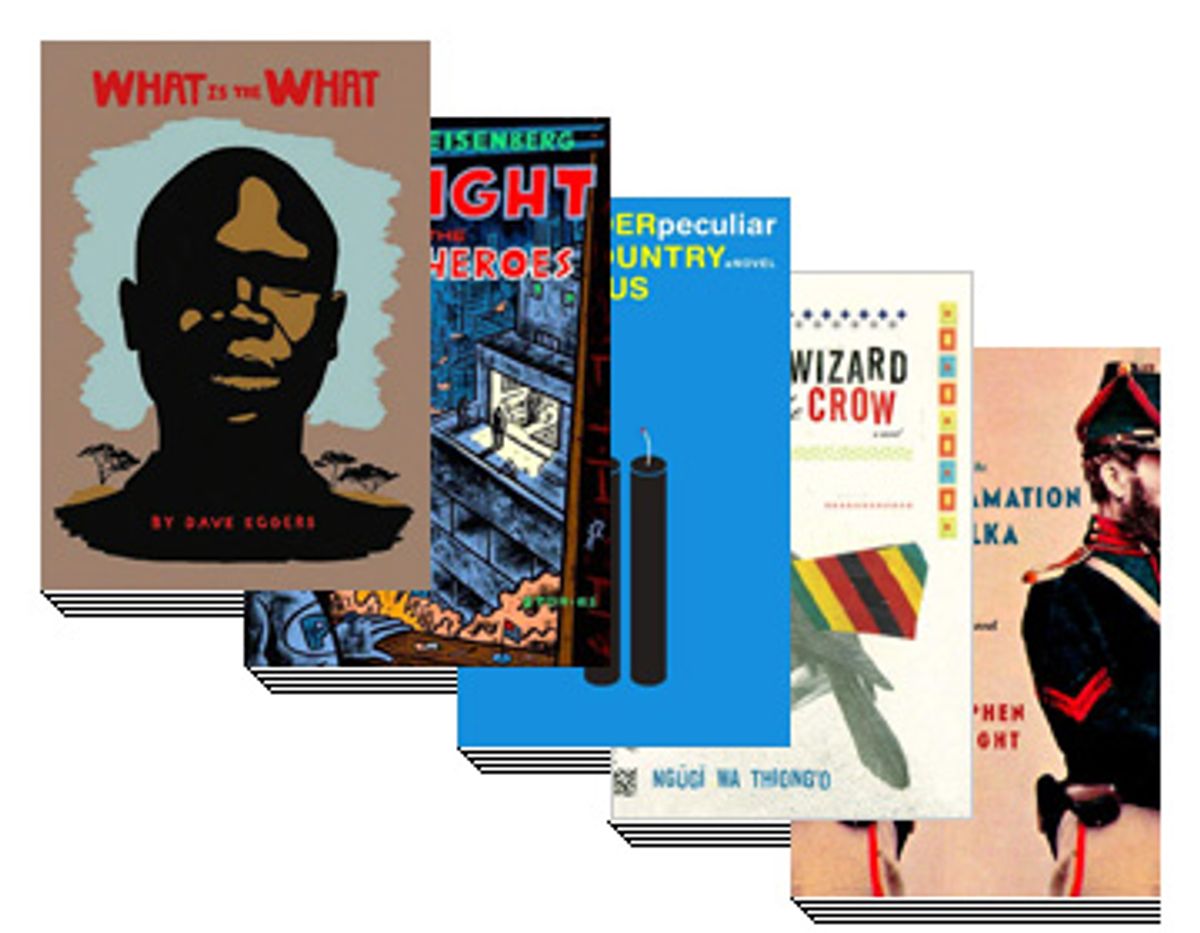

Africa, race and 21st century global paranoia are the prevailing themes in our favorite books this year -- less a reflection of the immediate moment than of the way ideas and events slowly make their way through the imaginations of talented writers and emerge, transfigured, long after the headlines have turned yellow. Literature, as Ezra Pound put it, is news that stays news. We expect that people will be reading these books for many, many years to come.

"What Is the What" by Dave Eggers

The unusual provenance of this novel -- Eggers has written it in the first-person voice of a real man, Valentino Achak Deng, and all of the events in the story are true, although not all of them happened to Deng -- is complicated. The result is sublime simplicity, the ego-less conveyance by Eggers of Deng's plain-spoken, gentle, world-weary but never hopeless voice. One of the Lost Boys of Sudan, Deng saw his village destroyed by Arab militiamen as a little boy and fled alone into a chaotic landscape before joining a troupe of similarly dispossessed boys on an epic journey on foot to a refugee camp in Ethiopia. Hunger, thirst, lions, crocodiles and soldiers on both sides of Sudan's civil war harried all of them and killed some. Deng finally made it to the promised land of America, but we know from the start that it proved to be no paradise. The novel's framing device -- Deng imagines telling his life story to thieves who beat and bind him while robbing his house and to the jaded officials who deal with the crime's aftermath -- is inspired; instead of making him pitiful, this silent appeal emphasizes Deng's remarkable, ineradicable dignity.

The unusual provenance of this novel -- Eggers has written it in the first-person voice of a real man, Valentino Achak Deng, and all of the events in the story are true, although not all of them happened to Deng -- is complicated. The result is sublime simplicity, the ego-less conveyance by Eggers of Deng's plain-spoken, gentle, world-weary but never hopeless voice. One of the Lost Boys of Sudan, Deng saw his village destroyed by Arab militiamen as a little boy and fled alone into a chaotic landscape before joining a troupe of similarly dispossessed boys on an epic journey on foot to a refugee camp in Ethiopia. Hunger, thirst, lions, crocodiles and soldiers on both sides of Sudan's civil war harried all of them and killed some. Deng finally made it to the promised land of America, but we know from the start that it proved to be no paradise. The novel's framing device -- Deng imagines telling his life story to thieves who beat and bind him while robbing his house and to the jaded officials who deal with the crime's aftermath -- is inspired; instead of making him pitiful, this silent appeal emphasizes Deng's remarkable, ineradicable dignity.

Read an interview with the author | Read an excerpt | Buy this book

Read an interview with the author | Read an excerpt | Buy this book

"Twilight of the Superheroes" by Deborah Eisenberg

Deborah Eisenberg's short stories seem ready-made for this age of overcommitment. In just a few deceptively straightforward pages you get all the depth, breadth and nuance that other writers require whole novels to build. The stories in this newest collection are all tinged to one degree or another by 9/11, but the attacks don't feature as significantly as the depredations of age, psychiatric fragility and that chronic weakness of Eisenberg characters, self-doubt. (Tellingly, the one story here that makes 9/11 its main focus -- the title story, unfortunately -- is the only disappointment.) What lifts Eisenberg's work above the usual fiction in this mode is her uncanny ability, shared only with Alice Munro, to conjure an entire multifarious life in the span of a few incidents. This gives her stories an unusual suspense; you're always waiting for the moment when the spell takes its effect and a human being materializes right before your very eyes.

Deborah Eisenberg's short stories seem ready-made for this age of overcommitment. In just a few deceptively straightforward pages you get all the depth, breadth and nuance that other writers require whole novels to build. The stories in this newest collection are all tinged to one degree or another by 9/11, but the attacks don't feature as significantly as the depredations of age, psychiatric fragility and that chronic weakness of Eisenberg characters, self-doubt. (Tellingly, the one story here that makes 9/11 its main focus -- the title story, unfortunately -- is the only disappointment.) What lifts Eisenberg's work above the usual fiction in this mode is her uncanny ability, shared only with Alice Munro, to conjure an entire multifarious life in the span of a few incidents. This gives her stories an unusual suspense; you're always waiting for the moment when the spell takes its effect and a human being materializes right before your very eyes.

Read an excerpt | Read a review | Buy this book

Read an excerpt | Read a review | Buy this book

"A Disorder Peculiar to the Country" by Ken Kalfus

It makes perfect sense that the best novel about 9/11 -- a collective memory by now encrusted in a layer of pieties -- would be a biting satire. Kalfus chronicles the awful divorce of New Yorkers Joyce and Marshall; things have gotten so acrimonious that when each one suspects the other has died in the tragedy, they both secretly rejoice. Don't mistake this for a book about how 9/11 affected our personal lives, though. Instead, it's for every nice middle-class American who pleads astonishment at the malice and savagery of the attacks. Kalfus shows us that the far-off national conflicts we find so baffling and complicated actually work a lot like a really bad divorce -- both are furious clashes between people who can't get along but who also can't escape each other. And let's face it: Most of us know a lot more about divorce than we do about the Middle East. The novel's story -- rich with betrayals and outrageous antics and a couple of expertly drawn and miserable kids -- never staggers under its thematic load. It remains always razor sharp, true to life, light on its feet and sneakily tragic.

It makes perfect sense that the best novel about 9/11 -- a collective memory by now encrusted in a layer of pieties -- would be a biting satire. Kalfus chronicles the awful divorce of New Yorkers Joyce and Marshall; things have gotten so acrimonious that when each one suspects the other has died in the tragedy, they both secretly rejoice. Don't mistake this for a book about how 9/11 affected our personal lives, though. Instead, it's for every nice middle-class American who pleads astonishment at the malice and savagery of the attacks. Kalfus shows us that the far-off national conflicts we find so baffling and complicated actually work a lot like a really bad divorce -- both are furious clashes between people who can't get along but who also can't escape each other. And let's face it: Most of us know a lot more about divorce than we do about the Middle East. The novel's story -- rich with betrayals and outrageous antics and a couple of expertly drawn and miserable kids -- never staggers under its thematic load. It remains always razor sharp, true to life, light on its feet and sneakily tragic.

Read an interview with the author and an excerpt | Read a review | Buy this book

Read an interview with the author and an excerpt | Read a review | Buy this book

"Wizard of the Crow" by Ngugi Wa Thiong'o

Novels about African dictatorships are supposed to be dour and educational, the literary equivalent of Brussels sprouts -- good for you if not especially tasty. The great Kenyan novelist Ngugi Wa Thiong'o capsizes that formula with "Wizard of the Crow," an outrageously entertaining, madcap political farce set in the fictional nation of Aburiria, whose despot is known only as The Ruler and has been running things for as long as anyone can remember. When the book's educated but destitute hero, fleeing a police constable, tries to throw the cop off his trail with a sign boasting of the awesome powers of the Wizard of the Crow, he inadvertently sets himself up as the sorcerer du jour. Soon, he's mixed up in the affairs of scheming government ministers, fatuous businessmen, a ruthless political climber and an elusive band of rebels. The novel is full of disguises, mistaken identities, tall tales, slapstick, hairs-breadth escapes and double-crosses. Ngugi's political satire is deep enough to apply to Midwestern regional marketing managers in addition to strutting West African tyrants -- aren't all tyrants the same, after all? -- because its real subject is human folly in all its many, hilarious and heartbreaking forms.

Novels about African dictatorships are supposed to be dour and educational, the literary equivalent of Brussels sprouts -- good for you if not especially tasty. The great Kenyan novelist Ngugi Wa Thiong'o capsizes that formula with "Wizard of the Crow," an outrageously entertaining, madcap political farce set in the fictional nation of Aburiria, whose despot is known only as The Ruler and has been running things for as long as anyone can remember. When the book's educated but destitute hero, fleeing a police constable, tries to throw the cop off his trail with a sign boasting of the awesome powers of the Wizard of the Crow, he inadvertently sets himself up as the sorcerer du jour. Soon, he's mixed up in the affairs of scheming government ministers, fatuous businessmen, a ruthless political climber and an elusive band of rebels. The novel is full of disguises, mistaken identities, tall tales, slapstick, hairs-breadth escapes and double-crosses. Ngugi's political satire is deep enough to apply to Midwestern regional marketing managers in addition to strutting West African tyrants -- aren't all tyrants the same, after all? -- because its real subject is human folly in all its many, hilarious and heartbreaking forms.

Read an interview with the author and an excerpt | Read a review | Buy this book

Read an interview with the author and an excerpt | Read a review | Buy this book

"Amalgamation Polka" by Stephen Wright

This is not your grandfather's Civil War novel, but who would expect that from Stephen Wright, that rare combination of literary wild man and flawless prose stylist? A Candide-like figure named Liberty Fish -- child of a renegade Southern belle and the Yankee abolitionist she eloped with -- joins the Union army and wends his way back to his maternal grandfather's plantation. Along the way, he meets all sorts of people -- pirates, soldiers, preachers and con men -- most of them driven half (or all the way) mad by their inability to make the American dream of freedom and the American reality of race add up to anything plausible. At the end of his journey he finds the heart of the nightmare in its ultimate, florid, night-blooming manifestation: his demented grandfather, Asa, trying to create -- avant Norman Mailer -- a white negro. This novel is a plummet down the black rabbit hole of American utopianism, with the brakes off and the seat belts removed, and it's one hell of a ride.

This is not your grandfather's Civil War novel, but who would expect that from Stephen Wright, that rare combination of literary wild man and flawless prose stylist? A Candide-like figure named Liberty Fish -- child of a renegade Southern belle and the Yankee abolitionist she eloped with -- joins the Union army and wends his way back to his maternal grandfather's plantation. Along the way, he meets all sorts of people -- pirates, soldiers, preachers and con men -- most of them driven half (or all the way) mad by their inability to make the American dream of freedom and the American reality of race add up to anything plausible. At the end of his journey he finds the heart of the nightmare in its ultimate, florid, night-blooming manifestation: his demented grandfather, Asa, trying to create -- avant Norman Mailer -- a white negro. This novel is a plummet down the black rabbit hole of American utopianism, with the brakes off and the seat belts removed, and it's one hell of a ride.

Read an excerpt | Read a review | Buy this book

Read an excerpt | Read a review | Buy this book

- - - - - - - - - - - -

What was your favorite book of 2006? E-mail us a few sentences about it at bestbooks@salon.com before Thursday and we'll publish your picks at the end of the week.

Shares