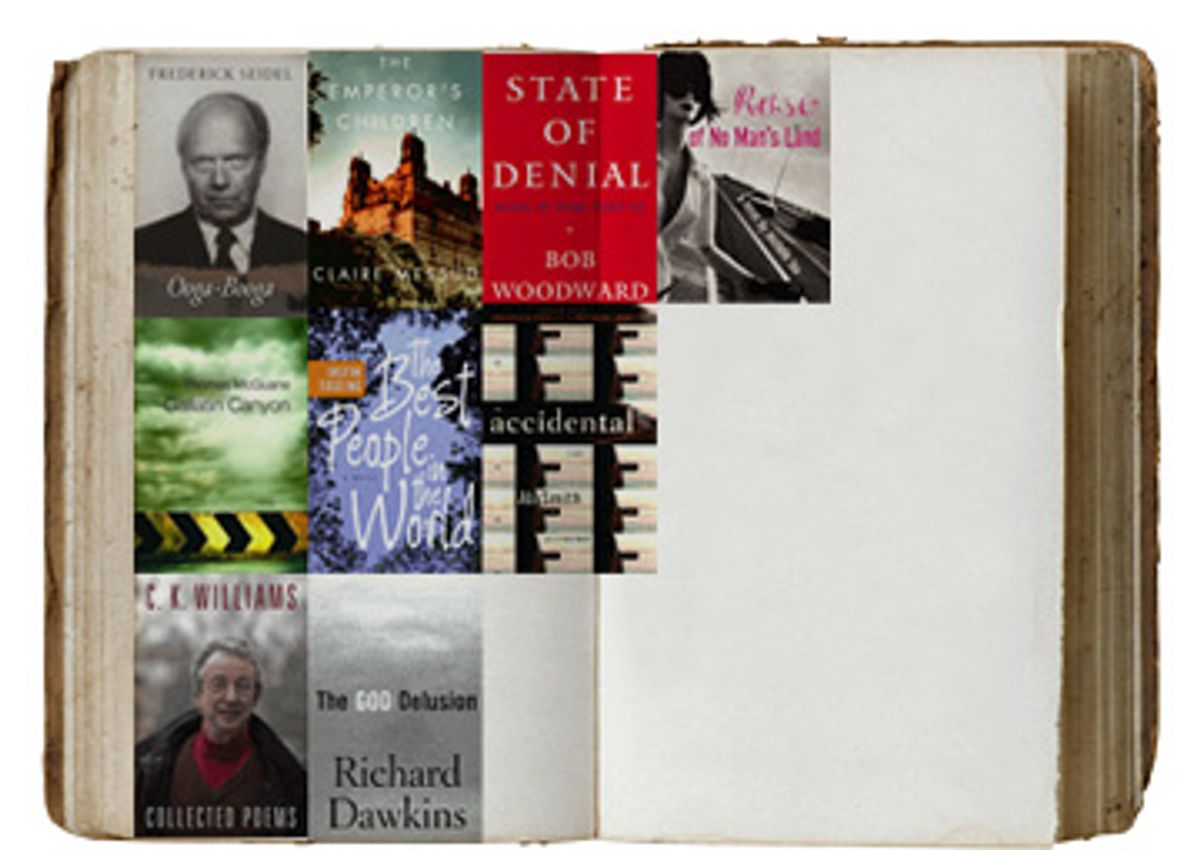

Earlier in the week we shared our favorite authors' picks for 2006, as well as our own selections of best debuts, best fiction and best nonfiction books of this year. Along the way we invited you to share with us -- and your fellow readers -- what book you loved most this year, and you responded with thoughtful, surprising and exciting choices. Here they are, with some suggestions from Salon staffers, too. There's surely something for everyone in this delighfully colorful mix.

-- Hillary Frey, Books Editor

- - - - - - - - - - - -

"The People's Act of Love" by James Meek is good enough to measure up to some of the classics. It's reminiscent in some ways of "Dr. Zhivago" because it is set in Russia in 1919; and it's a novel of ideas, but only as they are expressed through the characters' humanity. It's a thrilling adventure story also!

-- David Baynham

"Special Topics in Calamity Physics" by Marisha Pessl. A smart, funny and mysterious novel about Blue, a brainy teenager in an academic world. Structured around a syllabus for a great works of literature class, this is a wonderfully original novel with brilliantly developed characters and plot twists that will engage you right to the end. Pessl is a great new voice in literary fiction and an author to be watched.

-- Claire Benedict

Between the lines of relatives and lovers chiseled apart, lonely as hell and stoic as old cowboys, streaks a rare and deep compassion so stripped of sentimentality, and so powerful when it surfaces, that you realize Thomas McGuane is writing not as some old pro, spinning nostalgic tales from his Montana ranch, but writing with a bracing wisdom earned only through decades in the rough country, ages at the typewriter. So many images from "Gallatin Canyon," his first collection of stories in 20 years, will stick with me forever. And all of them, I realize, surprising and violent as they often are, are finally about the silent redemption of America's few unspoiled lands. In the remarkable "Miracle Boy," the teenage narrator navigates the insidious hostilities within his family, as his grandmother lay dying. An outpouring of emotion by his uncle disgusts his cold and ironic father, who ditches him and his mother; as it turns out, a blessing. "I thought my mother really had no chance to absorb the death of her own mother as long as my father was around," he writes. The boy and his mother go walking. "The clouds on the horizon made a band of light on the deep green Atlantic, and the breakers that lifted and fell with such gravity might have drowned our conversation, if there had been any. We must not have felt the need."

-- Kevin Berger, Salon Features Editor

My favorite book of 2006 was Ellen Kushner's "The Privilege of the Sword," which was a sharp and often hilarious take on social mores in a Regency setting. The characters leap off the page, and it maintains its exhilarating narrative to a breathtaking end.

-- Aliette de Bodard

Jeff VanderMeer's "Shriek: An Afterword" is full of the grotesque and the beautiful. The secret history of a family, and a city, it's the fantasy novel of the year, not to mention an absolutely gripping, luxurious read.

-- Gwenda Bond

For sheer storytelling prowess, my favorite novels of the year were Sara Gruen's "Water for Elephants" and Diane Setterfield's "The Thirteenth Tale." I read other books this year that were more poetically written, more "literary" perhaps, but none that swept me up so completely in the characters' lives and kept me with them long after I'd finished the book. Both were page-turners that I absorbed in a sitting or two, yet did not feel guilty about admitting I enjoyed.

-- Jennifer Boulden

Gore Vidal's opinions, creativity and wit have been vital companions throughout my life. His novels opened my eyes to the history of the United States; his opinions on government, entertainment and philosophy helped me formulate my own. The journey he began in his youth, chronicled exquisitely in the first volume of his memoirs, "Palimpsest," has eloquently continued in "Point to Point Navigation." I wish Mr. Vidal many more years of rich, creative life for I selfishly look forward to many more informative essays and the next volume of his memoirs.

-- Susan Bragg

"New Moon" by Stephenie Meyer. This series should not be ignored by adults because of its YA label. "New Moon" is filled with emotions every bit as intense and characters as memorable as those you'd find in an any epic romance, and the fact that some of the main characters are more/less than human should be popular with that growing sub-genre in both sci-fi and romance.

-- Anna Marie Catoir

I feel like "Memorial" by Bruce Wagner, a book with fine notices by an author with some heat, got lost in a shuffle, as no "Corrections"-like breakout novels leap to mind for 2006. Which seems a shame, as Wagner has only become more nuanced, as well as more heartwarming (not that difficult, given the downs and ups of the characters in his earlier novels) since the big splash of "I'm Losing You," his second novel. With each of his books he seems to swing for the fences -- his mainstay themes might be expressed religion, disease, celebrity, cruelty and failure -- and with arguable exception ("Force Majeure," I'd argue) he clears them handily, beautifully. He writes circles around far more famous rivals

-- Kip Conlon

Faiza Guene's "Kiffe Kiffe Tomorrow" was sometimes hard to read for its harsh truths but much harder to put down for its honest, sharp and often funny writing. This book, about being an outsider both in a culture and in your own skin, did more in its few, finely honed pages than many of the overblown, big books of the year.

-- Andrea Ferguson

"The Meaning of Night" by Michael Cox. The author has written a terrific first novel (albeit with credits editing numerous other works in and around Oxford) that allows the reader to feel like a fly on the wall in the time of Jack the Ripper in foggy old London. It is a satisfying compilation of romance, mystery, guilt, envy, murder and revenge that left me wishing, at story's end, that the tale had some more twists and turns on its way to resolution.

-- D. Fisher

"After This" by Alice McDermott was my favorite this year. A splendid book for boomers. McDermott takes us through our youth through the lives of one family. An astonishing accomplishment.

-- Karen Fredericks

I read so many fine books this year (including those on our lists this week), but I have to say again that I loved Justin Tussing's debut, "The Best People in the World." It's a road trip novel and a coming-of-age story, but most of all, a portrait of the desperation of first love. More remarkable, though, is Tussing's prose, which somehow manages to be both spare and outrageously visual; in simple, deliberate sentences he can paint a perfect scene -- of a dying house, of Vermont forests, of two young people making love. There is no doubt in my mind that this was the best overlooked book of 2006.

-- Hillary Frey, Salon Books Editor

"Exile on Main St." by Robert Greenfield tells the riveting story of the making of the Rolling Stones' celebrated double album amid the chaotic summer of 1971. Greenfield describes the Villa Nellcote in the South of France as the "hippest place in the world" where drugs, sex and rock all merge amid the conflicting personalities of Jagger and Richards. Mick writes the lyrics on a yellow legal pad and does not share his drugs. Keith is Keith, totally undisciplined, ingesting any drug available. Anita Pallenberg, Keith's beautiful girlfriend (who was also in the Stones' movie "Performance"), eventually becomes Jagger's girlfriend until Mick marries Bianca ... whew, what a soap opera! After reading this totally entertaining page-turner, I'm not surprised Keith Richards fell out of palm tree in Fiji recently!

--Harvey Gamm, V.P. Sales and Marketing

"The Accidental" by Ali Smith is the story of the seemingly accidental and temporary adoption of a free-spirited young woman by a dysfunctional English family on summer vacation. As the book is narrated by the four family members, we are exposed to a brief, confusing and oblique history of the young woman who calls herself Amber. Despite Amber's apparent near-sociopathic deceit and dishonesty, she manages to alter the lives of the individuals, but to unexpected ends. What makes this novel particularly fetching is Ms. Smith's humor and perception, and her ability to mimic and mock other writers' styles, while getting each character exactly right.

-- Stephen Ginsburg

Best fiction of the year: "The Foreign Correspondent" by Alan Furst. I have been waiting for this master of the WWII spy novel to finally cover the anti-Fascist Italians. Though when he did, I was afraid it wouldn't live up to the high standard set by earlier books like "Red Gold" and "The Polish Officer." But this is a tour de force. Paris 1939 was the epicenter of resistance espionage. Many of Furst's earlier characters make appearances, but our hero is from Italy this time and we go from Paris to Civil War Spain to Berlin to Genoa to Marseilles. It's a great and moving tale.

-- Joanna Hamil

The best book of fiction I read this year was Richard Ford's "The Lay of the Land." This is the finale (if Ford is to be taken at his word, which, why not, he's not a politician) of the Frank Bascombe trilogy, which began with "The Sportswriter" in 1986 and continued in 1996 with the Pulitzer- and PEN/Faulkner-award winner "Independence Day" (the first and so far only book to win both the Pulitzer and PEN/Faulkner). What makes Ford so special, especially when writing in Frank Bascombe's voice, is the way his sentences meander, taking their time, one richly evocative clause after another. In a lesser writer's hands, such lengthy sentences would seem flabby -- but Ford manages to fill them with increasing amounts of tension, like a rubber band being stretched just up to but never beyond its breaking point, and by the time you get to the period, the rubber band snaps back and leaves a satisfying ping of an epiphany. The characters are full-bodied (like a good wine?) and satisfyingly flawed and never beyond redemption. They are wholly real. A hundred years from now, readers will still be marveling at the Bascombe trilogy.

-- Scott O. Handy

"The Brief History of the Dead" by Kevin Brockmeier -- a chilling, non-sappy treatment of heartbreaking themes like death, love, global destruction; an unusual plot that portrays the afterlife even more inventively than Alice Sebold's "The Lovely Bones"; and amazing writing that sucks you in from the start and keeps you frantically flipping the pages until the end.

--Karyn Hinkle

"Collected Poems" by C.K. Williams. His first major poem was about Anne Frank; many of his most recent touch on the Iraq war and the complexities of life today, the intersection of the public and the personal. No quiet navel-gazer, Williams has for over 40 years been that rare poet unafraid to tackle head on the largest themes: war and its repercussions, the battles of the races and sexes, the joy and exhaustion of family. His signature long lines and narrative drive also make him both accessible and appealing to many who prefer prose or feel intimidated by much contemporary poetry.

-- Steve Kasdin

"Blue Arabesque: A Search for the Sublime" by Patricia Hampl was my favorite. This tiny exuberant book carries within it no less than the hidden mystery of the healing essence of art. As the author reveals, it is the pursuit of the sublime that allows art to speak to us and jolt us into exaltation beyond space and time. I love Patricia Hampl's prose. Her metaphor for her search for the Holy Grail of healing by art is that of Matisse's "Woman Before an Aquarium."

-- Ron Kendricks

It's not often these days that I have the time, or the inclination, to knock off a 411-page book in two days, but Michael Pollan's "The Omnivore's Dilemma" just screams for that kind of attention. Frankly, someone at his publishing house needs to rethink their subhead style, because describing the book simply as "a natural history of four meals" doesn't do it justice. This is a book about food, sure, but more than that it's an account of just how profoundly the way this country eats affects every aspect of our society and policy. Such a subject could be horribly dull, but Pollan manages to imbue it with a real voice and narrative, not to mention a wealth of shocking information.

-- Alex Koppelman, Salon staff writer

Peter Behrens' "The Law of Dreams" was the best first novel I read this year. Fergus, his family's sole survivor of the Great Famine, lives an entire life in a single year as he makes his way from Ireland to Canada. "The Book of Lost Things," by John Connolly was the best novel by a previously published writer. Twelve-year-old David loses his mother and his ordinary life during the Second World War, and retreats into a world of books; what he finds is that the fairy-tale world is just as dangerous as the "real" one. This is a book for everyone who ever sought refuge in books, and one people will be reading for generations.

-- Ellen Clair Lamb

"The Omnivore's Dilemma" by Michael Pollan made me want to become a vegetarian. I did not want to eat for a week and it has started me really thinking about where I buy my food and what I eat. A real eye-opener.

-- Gilbert Maker

"The Willow Field" by William Kittredge was my favorite. Gorgeous prose of the sort only William Kittredge can write, about a West that no longer exists, but far from nostalgic. "These people wait in a web of dreams, as if the old days might return..." They won't and the old days weren't even the old days when they were the old days. This book gives them back to us, though -- in all their sometimes quiet, sometimes brutal glory.

-- Peter Orner

As a devotee of traditional beginning-middle-end storytelling I have absolutely no explanation for the fact that I was completely seduced by the wheels-within-wheels metafictional games of Jennifer Egan's "The Keep." If you want the high-concept version, think early John Barth meets late Stephen King. The ending may go one twist too far, but you'll be so entertained you won't care.

-- Michael Padgett

Without a doubt, Cormac McCarthy's "The Road" was my favorite. It has been many years since I have felt so totally absorbed by a novel. The "new world" McCarthy so meticulously and yet concisely describes is a character in itself, and one that I just can't shake even weeks after concluding the book.

-- Roxanna Pisiak

Earlier in the year Patrick Ryan released his debut, titled "Send Me." Reading it transported me from the middle of a New York City winter to a very hot and sticky situation, both weather- and sibling/parental-related, in Central Florida. His simple prose and colorful characters, plucked straight out of Richard Russo land, made "Send Me" a very enjoyable read. Also, the original use of non-linear storytelling put forth by Mr. Ryan was highly effective -- I had no idea how it was going to end. But it all made perfect sense once I finished.

--Alan Roberts

I would nominate "Suite Frangaise," by Irhne Nimirovsky, available in French and in English translation. The book itself was discovered in the 1990s by the author's daughter -- two handwritten novellas, out of a projected five, the remainder unfinished at the time of the author's death in a Nazi concentration camp in 1942. They are a brutal, unsparing look at wartime France, written in a luminous, almost cinematographic style. Nimirovsky's portrait transcends its period, as a firsthand testimonial to the nobility, and failure, of human beings in the face of terrible events.

-- Jonathan Scoll

Book of the Year: "Suite Française" by Irène Némirovsky. OK, the year is 1941. But this novel, written with unimaginable confidence and restraint, amid the chaos and carnage of the fall of France, may be as close as we will come to a fusing of contemporaneous history and literature.

Nonfiction Book of the Year: "State of Denial" by Bob Woodward. It's rare (especially for followers of the Woodward oeuvre) that a book this influential in the political debates is actually readable. Whatever happened in the Woodward book factory to produce it is one of the major Washington events of the year.

Novel That I Most Recommended to Friends: "Water for Elephants" by Sara Gruen. No it's not epic literature, but I was gripped by this account of circus life in the 1930s. It also wins the award for the best unexpected and, yes, heartwarming ending of the year.

-- Walter Shapiro, Salon Washington Bureau Chief

My pick is "The Thin Place" by Kathryn Davis. This mysterious novel -- as haunting and magical as Davis' masterpiece, "The Girl Who Trod on a Loaf" -- somehow makes the reader deeply care about dozens of characters (and animals) in a small New England village. It also manages to dip in and out of eons of time. I'm really surprised this hasn't made any of the "10 Best" lists published so far; it's one of those rare novels I could imagine rereading instantly.

-- Ted Schaefer

Richard Dawkins' "The God Delusion" was my favorite book of 2006. Although the tone was hectoring at times and Dawkins' prose not as well-crafted as in his scientific books, the intellectual fearlessness was invigorating and his arguments well-reasoned. And it seems his work, along with that of Sam Harris and Daniel Dennet, has created a stir in our otherwise complacent society.

-- Sanford Sharp

With "Rose of No Man's Land," Michelle Tea moves from being the sharpest eye on the queer underground ("Valencia," "Rent Girl") to the torch-carrier of the comic coming-of-age novel. No other book this year had me laughing and wincing in perfect balance at the memory of what it was to be a high school freshman making every exciting wrong choice.

-- K.M. Soehnlein

Joanne Harris' "Gentlemen & Players" is the gold standard for this year's best mystery. Set around an exclusive English boys school, it's filled with plot twists, possible red herrings, and solid narrative voices and pacing. It left me breathless, completely suckered, at points -- a delightful read.

-- Sheila Stanley

As one who has traveled to Afghanistan twice in the last three years, and easily devoured 25 books about the place, I cast my vote for Rory Stewart's "The Places in Between" as the best book of 2006 and the best book about that country and its people. Stewart has an appealing view of the world and its people, open to understanding the customs and observing the way of life he meets as he walks across Afghanistan in January 2002. That he did not die is a testament to this man and his dog -- a Mastiff he adopts early on and a typical marvelous thread the reader follows with deep engagement. The author's description of the world he meets, including, for example, people's toilet behavior, is in no way gross, but is typical of the detail and vividness of this book.

-- Laura Stevens

Karen Armstrong's "The Great Transformation: The Beginning of Our Religious Traditions" is an important book, in this year when religion is running amok in our country. Armstrong writes about religion, mythology and belief in ways that engage both non-believers and believers. (Maybe not True Believers). She traces the changes in religious beliefs from early beginnings in bloody sacrifice to more humanistic Golden Rule practices. The book starts around 900 B.C. with middle European hunter-gatherers, then moves to China, India, Greece and the Middle East, and ends around 200 A.D. By the time Judaism and Christianity show up we can see where many of the beliefs in those faiths came from. Great notes and bibliography. This may sound kind of dense but really it's quite thrilling -- Armstrong is a swell writer!

-- Pat Stoll

I know a lot has been made of the over-the-top style of Marisha Pessl's debut, "Special Topics in Calamity Physics," but I thoroughly enjoyed it. I actually found the style to be consistent with the age and precociousness of the narrator. It's definitely the best fiction book published this year that I read.

-- Kate Teffer

I realize I'm not alone in this, but my favorite book of the year was Claire Messud's "The Emperor's Children." It brought back to life and then neatly eviscerated a post-synergy, pre-Sept. 11 New York City in devastating detail. Messud nailed not only the city's vainglorious peaks, but the sticky crevices of its often passionless ambition, and it still makes me squirm to think of exactly how familiar some of the characters felt.

-- Rebecca Traister, Salon staff writer

Well, Salon, once again you've let us all down by completely ignoring the genre of poetry! My favorite poetry book of 2006 is "Ooga-Booga," by Frederick Seidel, who is something of a literary outsider. I can't describe in a few sentences how utterly unique this stuff is. These poems are frightening, suave, spooky, silly, brutal, mesmerizing, perverse. The lines have a free-flowing rigidity, an off-the-wall stateliness that is always surprising. His subjects range from sex to mortality to geopolitics to high-end fashion to Italian motorcycles to all these things wrapped up together, but whatever he's writing about, he always does it with an honesty that spares nothing and no one.

-- Matt Walker

I rediscovered the public library this year, so I had the pleasure of reading a lot of the books that in earlier years I would just have perused in the bookstore. Hands down, my favorite was "Brookland" by Emily Barton. An absorbing, detailed quasi-historical novel, it tells the story of the Winship sisters and their gin distillery (!) on the shores of 18th century Brooklyn, N.Y. At that time the borough was a pastoral backwater, with bustling Manhattan only accessible by rowboat ferry. The heroine, Prudence, runs the distillery by day and dreams of constructing a high-flying wooden bridge over the river by night. Her struggle to realize her dream, while keeping the family business going (who knew that the minutiae of crushing herbs to flavor gin could be so lyrical?) and living with her mercurial sisters and supportive husband, make the novel so resonant to the modern, multitasking woman. A beautifully imagined blend of historical fact and inventive whimsy, the book was so satisfying I nearly flipped right back to the beginning once I finished it.

-- Emily Woodward

Julia Child, with Alec Prud'homme, "My Life in France": In this delightful, spirited memoir, the woman who introduced Americans to the pleasures of French food recounts her early years of married life in postwar France, her training at Le Cordon Bleu, and the arduous but rewarding task of cookbook writing. Most amazingly, she describes in lush detail meals she ate in France as far back as the mid-'40s: Potently briny oysters, rye bread dotted with unsalted butter, Dover sole "perfectly browned in a sputtering of butter sauce." Child died in 2004, but this book suggests she was sharp until the last: The only thing greater than her recall is her charm.

-- Stephanie Zacharek, Salon film critic

My pick is "Blue Nude" by Elizabeth Rosner. Its roots live in the nightmare of the Holocaust of the 1940s. Weaving together the stories of the daughter of a Holocaust survivor and her experiences growing up with the equally troubling stories of the son of a Nazi, we see glimmers of a new way of being through these difficult situations.

-- Christine Zecca

Readers also wrote in to suggest the following titles:

"The Inheritance of Loss" by Kiran Desai; "The Stolen Child" by Keith Donohue; "In the Company of the Courtesan"; "Kensington Gardens" by Rodrigo Fresan; "A Godly Hero: The Life of William Jennings Bryan" by Michael Kazin; "The Ha-Ha" by Dave King; "Lisey's Story" by Stephen King; "Widdershins" by Charles de Lint; "Clemente: The Passion and Grace of Baseball's Last Hero" by David Maraniss; "Black Swan Green" by David Mitchell; "They Call Me Naughty Lola: Personal Ads From the London Review of Books" by David Rose; "Changeling" by Delia Sherman; "The Ruins" by Scott Smith; "Eat the Document" by Dana Spiotta; "The Courtier and the Heretic" by Patrick Stewart; "Flapper: A Madcap Story of Sex, Style, Celebrity, and the Women Who Made America Modern" by Joshua Zeitz

Shares