Despite massive scientific corroboration for evolution, roughly half of all Americans believe that God created humans within the past 10,000 years. Many others believe the "irreducible complexity" argument of the intelligent design movement -- a position that, while somewhat more flexible, still rankles most scientists. This widespread refusal to accept evolution can drive scientists into a fury. I've heard biologists call anti-evolutionists "idiots," "lunatics" ... and worse. But the question remains: How do we explain the stubborn resistance to Darwinism?

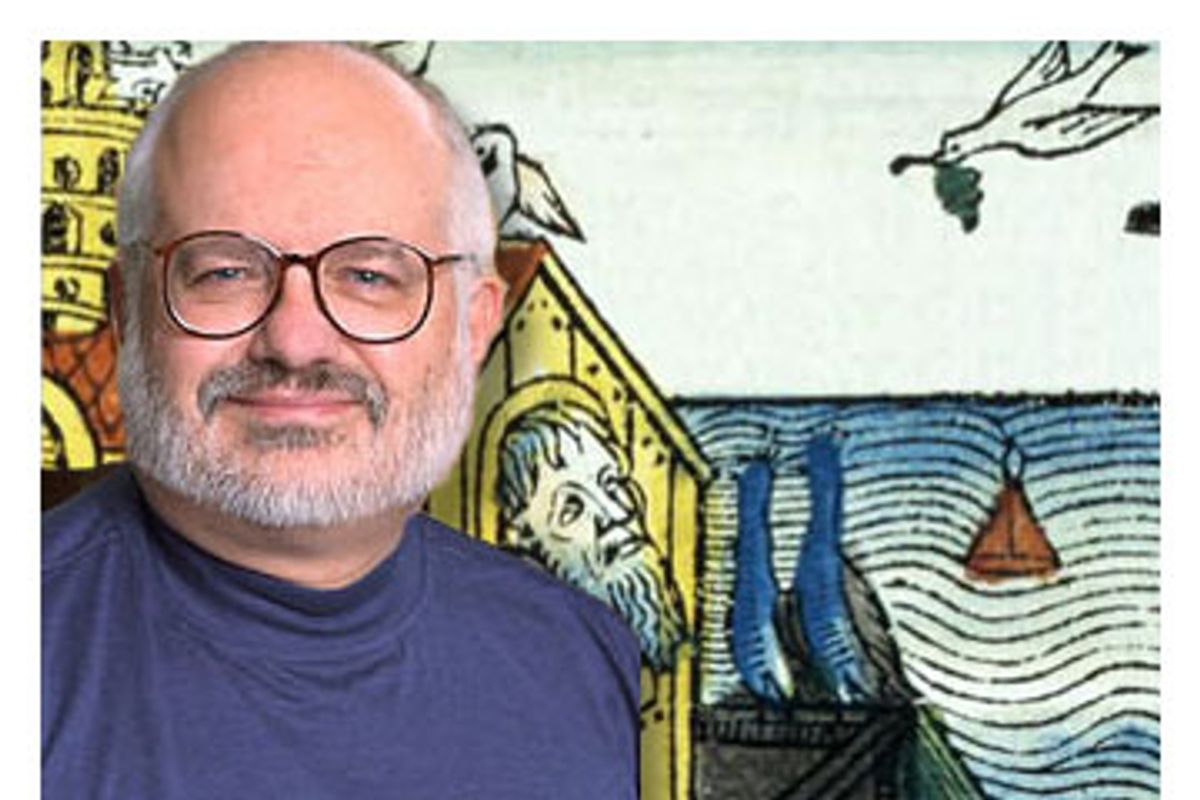

University of Wisconsin historian Ronald Numbers is in a unique position to offer some answers. His 1992 book "The Creationists," which Harvard University Press has just reissued in an expanded edition, is probably the most definitive history of anti-evolutionism. Numbers is an eminent figure in the history of science and religion -- a past president of both the History of Science Society and the American Society of Church History. But what's most refreshing about Numbers is the remarkable personal history he brings to this subject. He grew up in a family of Seventh-day Adventists and, until graduate school, was a dyed-in-the-wool creationist. When he lost his religious faith, he wrote a book questioning the foundations of Adventism, which created a huge rift in his family. Perhaps because of his background, Numbers is one of the few scholars in the battle over evolution who remain widely respected by both evolutionists and creationists. In fact, he was once recruited by both sides to serve as an expert witness in a Louisiana trial on evolution. (He went with the ACLU.)

Numbers says much of what we think about anti-evolutionism is wrong. For one thing, it's hardly a monolithic movement. There are, in fact, fierce battles between creationists of different stripes. And the "creation scientists" who believe in a literal reading of the Bible have, in turn, little in common with the leaders of intelligent design. Numbers also dismisses the whole idea of warfare between science and religion going back to the scientific revolution. He argues this is a modern myth that serves both Christian fundamentalists and secular scientists.

Numbers stopped by my radio studio to talk about the competing brands of creationism, his quarrel with atheism and his breaking with faith, and why some famous scientists -- like Galileo -- hardly deserve the label "scientific martyr."

Given the overwhelming scientific support for evolution, how do you explain the curious fact that so many Americans don't believe it?

I don't think there's a single explanation. To many Americans, it just seems so improbable that single-celled animals could have evolved into humans. Even monkeys evolving into humans seems highly unlikely. For many people, it also conflicts with the Bible, which they take to be God's revealed word, and there's no wiggling room for them. And you have particular religious leaders who've condemned it. I think there's something else that I hate to mention but probably is a serious contributing factor. I don't think evolution has been taught well in the United States. Most students do not learn about the overwhelming evidence for evolution.

At the university level or the high school level?

Grade school, high school and university. There are very few general education courses on evolution for the nonspecialist. It's almost assumed that people will believe in evolution if they've made it that far. So I think we've done a very poor job of bringing together the evidence and presenting it to our students.

There's a stereotype that creationists just aren't that smart. I mean, how can you ignore the steady accumulation of scientific evidence for evolution? Is this a question of intelligence or education?

Not fundamentally. There is a slight skewing of anti-evolutionists toward lower levels of education. But it's not huge. One recent poll showed that a quarter of college graduates in America reject evolution. So it's not education itself that's doing this. There are really dumb creationists and there are really dumb evolutionists. Of the 10 founders of the Creation Research Society, five of them earned doctorates in the biological sciences from major universities. Another had a Ph.D. from Berkeley in biochemistry. Another had a Ph.D. from the University of Minnesota. These were not dumb, uneducated people. They rejected evolution for religious and, they would say, scientific reasons.

But that's so hard to understand. If you get a graduate degree in the biological sciences, how can you still allow religion to trump science?

They don't see it that way. They see religion as informing their scientific choices. I think it's extremely hard for human beings to see the world as others see it. I have a hard time seeing the world as Muslim fundamentalists see it. And yet, there are many very smart Muslims out there who have a totally different cosmology and theology from what I have. I think one of the goals of education is to help students, and perhaps help ourselves, see the world the way others see it so we don't just judge and say, "They're just too stupid to know better."

My guess is that the most persuasive arguments for evolution are not going to come through scientific reasoning. They're going to come from scientists, and from theologians and other people of faith, who say you can believe in God and still accept evolution, that there's nothing incompatible about the two. Do you agree?

To a large extent, I do. But I think the influence of those middle-ground people is limited. Conservatives don't trust them. They think they've already sold out to modernism and liberalism. And a lot of the more radical scientists spurn them as well. Richard Dawkins, for example, would argue that evolution is inherently atheistic. That's exactly what the fundamentalists are saying. They agree on that. So you have these people in the middle saying, "No, no. It's not atheistic for me. I believe in God and maybe in Jesus Christ. And in evolution." Having these loud voices on either side of them really tends to restrict the influence that they might otherwise have.

If you're going to persuade devout Christians to accept evolution, don't you also have to show that you can't read the Bible literally, especially the story of Genesis?

Good luck! They do read it literally. Six thousand years, six 24-hour days, a worldwide flood at the time of Noah that buried the fossils, people that lived over 900 years before the flood. There are millions of people who don't seem to have much trouble reading it literally.

What about those creation scientists with Ph.D.s at the Creation Research Society? That's what is hard to understand.

Well, most people who reject evolution do not see themselves as being anti-scientific in any way. They love science. They love what science has produced. It's allowed the conservative Christians to go on the airwaves, to fly to mission fields. They're not against science at all. But they don't believe evolution is real science. So they're able to criticize one of the primary theories of modern science and yet not adopt an anti-scientific attitude. A lot of critics find that just absolutely amazing. And it's a rhetorical game that has been played fairly successfully for a long time. In the latter part of the 19th century, when Mary Baker Eddy came up with her system that denied the existence of a material world -- denying the existence of sickness and death, which flew in the face of everything that late 19th century science was teaching -- what did she call it? "Christian science." The founder of chiropractic thought that he had found the only true scientific view of healing. The creationists around 1970 took the view that's most at odds with modern science and called it "creation science." They love science! And they want to partake in the cultural authority that still comes to science.

Given your field of study, you have a particularly interesting personal history. You grew up in a family of Seventh-day Adventists.

That's correct. All my male relatives were ministers of one kind or another.

All? Going how far back?

Both my grandfathers. My maternal grandfather was president of the international church. My father and all my uncles on both sides worked for the church. My brother-in-law is a minister. My nephew is a minister.

Did you go to Adventist schools?

First grade through college. I graduated from Southern Missionary College in Tennessee.

And what did you think about life's origins as you were growing up?

I was never exposed to anything other than what we now call "young earth creationism." Creation science came out of Seventh-day Adventism. My father was a believer, all my teachers were believers, all my friends believed in that. I can remember as a college student -- I majored in math and physics -- there was a visiting professor from the University of Chicago lecturing on carbon-14 dating, and he was talking about scores of thousands of years. And my friends and I just looked at each other, wincing and smiling, saying he just didn't know the truth.

But at some point, your ideas obviously changed. What caused you to question the creationist account?

I wish I knew. There are a few moments that proved crucial for me. I went to Berkeley in the '60s as a graduate student in history and learned to read critically. That had a profound influence on me. I was also exposed to critiques of young earth creationism. The thing that stands out in my memory as being decisive was hearing a lecture about the fossil forest of Yellowstone, given by a creationist who'd just been out there to visit. He found that for the 30 successive layers you needed -- assuming the most rapid rates of decomposition of lava into soil and the most rapid rates of growth for the trees that came back in that area -- at least 20,000 to 30,000 years. The only alternative the creationists had to offer was that during the year of Noah's flood, these whole stands of forest trees came floating in, one on top of another, until you had about 30 stacked up. And that truly seemed incredible to me. Just trying to visualize what that had been like during the year of Noah's flood made me smile.

Did your beliefs come crashing down at that moment?

Well, the night after I heard that, I stayed up till very, very late with a fellow Adventist graduate student, wrestling with the implications of it. Before dawn, we both decided the evidence was too strong. This was a crucial night for me because I realized I was abandoning the authority of the prophet who founded Adventism, and the authority of Genesis.

You went on to write a book about Ellen White, the founder of the Seventh-day Adventists. Didn't that prove to be quite controversial?

It did. I wrote about her as a historian would, without invoking supernatural explanations. That bothered a lot of people because according to traditional Adventism, she was a chosen of God, who would take her into visions, where she would see events past, present and future. Once, God actually took her back to witness the Creation. And she saw that the Creation occurred in six literal 24-hour days. Which made it impossible for most Adventists to play around with symbolic interpretations of Genesis. I also found in my research that she had been copying some of her so-called testimonies, which were supposed to be coming directly from God. So it did create something of a stir.

That must have created trouble for you in your own family of Adventists.

It did. And it created trouble for my father, who was a minister. Some church ministers were very harsh with him. Here I was, about 30 or so. They were telling him he had no right being a minister if he couldn't control his son. So he took early retirement.

Because of your book?

Yes. He was thoroughly humiliated by this.

Did he try to talk you out of the book?

Oh yes. We had hours and hours of argument. He had a limited number of explanations for why I would be saying this about the prophetess. One was that I was lying. But he knew me too well, so the only explanation left for him was that somehow Satan had gained control of my mind. And what I was writing reflected the power of Satan. For a number of years, he could not bear to be seen in public with me.

Did you ever heal that rift?

We did. Some information came out a number of years later that he read before he died. It showed that the early ministerial leaders of the church had some of these qualms and decided to bury it. So he regretted that the church had not dealt with this issue a hundred years earlier and come clean. Before he died, he said, "I understand you now. And I understand what you said about Ellen White is probably true. But if I fully accept the implications of what you're saying, I'd have to give up all my religious belief." And I said, "Dad, I don't want you to. It's too important for you."

What are your religious beliefs now?

I don't have any.

Are you an atheist?

I don't think so. I think that's a belief -- that there's no God. I really wanted to have religious beliefs for a long time. I miss not having the certainty of religious knowledge that I grew up with. But after a number of years of trying to resolve these issues, I decided they're not resolvable. So I think the term "agnostic" would be best for me.

You mentioned that Seventh-day Adventism actually played a crucial role in the history of creationism. Didn't an early Adventist lay out the whole idea of "flood geology"?

Exactly. George McCready Price, a disciple of Ellen White's, came along in the early 20th century and made Noah's flood the key actor in the history of life on earth. He tried to show that the conventional interpretations of the geological column were fallacious and that, in fact, the entire geological column could have been deposited in about one year. And that became the centerpiece of what he called "the new catastrophism."

Then, in about 1970, that view -- flood geology -- was renamed "creation science" or "scientific creationism." Two fundamentalists -- a theologian named John Whitcomb Jr. and a hydraulic engineer named Henry Morris -- took Price's flood geology, reworked it a little bit and published it as "The Genesis Flood." Notice that the seminal books in the history of creationism have focused on geology and the flood, not so much on biology. And as a result of what Whitcomb and Morris did, Price's views exploded among fundamentalists and other conservative Christians.

But why did this particular version of creationism catch on? Why did Noah's flood somehow resolve all the contradictions in the fossil record?

Your question is all the more difficult to answer because fundamentalists had two perfectly orthodox interpretations of Genesis One that would have allowed them to accept all of the paleontological evidence. One was that the days of Genesis represented vast geological epochs, or even cosmic epochs. William Jennings Bryan accepted that. The founder of the World Christian Fundamentals Association accepted that.

So in that account, you could have the Earth going back billions of years.

Time was no problem. Another view, very popular among fundamentalists, was called the gap theory. After the original creation, when God created the heavens and the Earth, Moses -- the author of Genesis -- skipped in silence a vast period of Earth history before coming to the Edenic creation in six days, associated with Adam and Eve. Those fundamentalists and Pentecostals could slip the entire geological column into that period between the original creation and the much, much later "Edenic restoration." You had these perfectly good interpretations of Genesis available to fundamentalists. So why would they accept this radical, reactionary theory that everything was created only about 6,000 or 7,000 years ago?

I'm willing to bet you have some explanation. Why did flood geology suddenly explode in popularity in the 1960s?

The biggest explanation, I think, is that for more than a hundred years, Christians had been reinterpreting God's sacred word -- the Bible -- in the light of new scientific discoveries. And people like Whitcomb and Morris, the authors of "The Genesis Flood," struck a really sensitive chord when they said, "It's time to quit interpreting God in the light of science, and start with God's revealed word and then see if there's any model of Earth history that will fit with that."

Otherwise, science keeps chipping away at religion.

Exactly. It never ends. It always changes and it means you'll have to be constantly reinterpreting God. It wasn't so much that they invested in the Genesis account as that many of them were concerned about the last book of the Bible. Revelation foretold the end of the world. And they would argue, how can we expect Christians to believe in the prophecies of Revelation, about end times, when we symbolically interpret Genesis, and interpret it away? So if you want people to take Revelation seriously, you have to get them to take Genesis really seriously.

More recently, we've had the intelligent design movement. I know some people just see this as a new version of creationism, stripping away all the talk about God and religion so you can teach it in the schools. Is that true?

There's a little bit of evidence to support that. But I think that both demographically and intellectually, it doesn't hold a lot of water. The intelligent design leaders are people, by and large, who do not believe in young earth creationism.

So they would accept the Earth's being four-and-a-half billion years old.

That's not an issue with most of them. They want to create a big tent for all anti-evolutionists, even non-Christians. Whitcomb and Morris and the Creation Research Society wanted to create a tightly knit group of people who all subscribed to flood geology. The intelligent design leaders say it's premature to insist on a particular interpretation of Genesis. This approach has really irritated many of the young earth creationists, who feel they're being told by these intellectual leaders of intelligent design, "You're just a divisive group dedicated to a particular interpretation of Scripture." They are. But they've been very successful. And they're not about to abandon their crusade to get people to accept scientific creationism in favor of some mushy intelligent design.

The intelligent design leaders insist that they are doing science. Michael Behe has said that the scientific discovery of "irreducible complexity" should rank in the annals of the history of science alongside the discoveries of Newton and Lavoisier and Einstein. They're after something much bigger than a natural theology. They want to change one of the most fundamental ground rules for practicing science. Around 1800, the practitioners of science reached a consensus that whatever they proposed would have to be natural.

Not supernatural. You can never resort to a supernatural explanation in science.

Exactly. To be scientific meant to be natural. But it said nothing about the religious beliefs of these people. Evangelical Christians believed that; liberal Christians believed that; secularists believed that's the way we're going to do science. And it worked out beautifully. But the leaders of the intelligent design movement, beginning with Berkeley, Calif., lawyer Philip Johnson, have wanted to re-sacralize science. They want to ditch the commitment to naturalism and allow for supernatural explanations. That's the most radical revolution I can imagine in doing science. And many Christians who are scientists don't want to do that.

Now, one thing I find curious is your own position in this debate. Your book "The Creationists" is generally acknowledged to be the history of creationism. You've also been very upfront about your own lack of religious belief. Yet, as far as I can tell, you seem to be held in high regard both by creationists and by scientists, which -- I have to say -- is a neat trick. How have you managed this?

Unlike many people, I haven't gone out of my way to attack or ridicule critics of evolution. I know some of the people I've written about. They're good people. I know it's not because they're stupid that they are creationists. I'm talking about all my family, too, who are still creationists. So that easy explanation that so many anti-creationists use -- that they're just illiterate hillbillies -- doesn't have any appeal to me, although I'm quite happy to admit that there are some really stupid creationists.

Can you put the current battles over evolution in some historical context? If we take this history back to the scientific revolution -- back to Newton and Galileo -- was there a war between science and religion then?

There were conflicts at times. But there was no inevitable war. Just think about it. Most of the contributors to the so-called scientific revolution were believers. They were theists. They didn't see any inherent conflict between what they were doing and their religious beliefs.

These were the giants -- Newton, Galileo, Boyle, Kepler. Weren't they all devout Christians?

Well, Newton was a little lax at times, though he was certainly a theist. Boyle was a good sound Christian. I think Galileo was a true believer in the church. And Copernicus was a canon in the Catholic Church. Kepler was a deep believer in God. So yeah, these people were believers. Occasionally, there were problems -- for instance, between Galileo and the pope. But Galileo had gone out of his way to insult the pope, who had previously supported him. He put the pope's favorite argument against heliocentricism into the mouth of the character Simplicio -- the simple-minded person.

So Galileo wasn't really arrested because of his science. It was because he was a lousy diplomat?

Yeah, he was a terrible diplomat, thumbing his nose at the most powerful person who critiqued him. Also, Galileo was not as badly treated as many people suggest. When he was summoned down to Rome by the Inquisition, he lived in the Tuscan palace. And then when he was asked to move into the Vatican, to the palace of the Inquisition, one of the officials in the Inquisition vacated his three-room apartment so that the distinguished guest, Galileo, could have a nice apartment. And they allowed him to have his meals catered by the chef at the Tuscan embassy. Ultimately, he was under house arrest in his villa outside of Florence.

Is the whole notion, then, that Galileo faced possible execution because of his scientific statements just baloney?

[It was] highly unlikely [he faced execution]. In fact, I don't know of a single pioneer in science who lost his life for his scientific beliefs.

Well, what about the 16th century philosopher and cosmologist Giordano Bruno? I've always heard that he was burned at the stake because of his Copernican view of the universe.

No, it was for his theological heresies, not for his Copernicanism. He happened to be a Copernican, but that's not what got him into trouble. No, the bitterest arguments have taken place within religious groups. If you want to hear bitter argument, listen to some old age fundamentalists argue with young earth creationists. Then you're talking about warfare.

If science and religion aren't really historical enemies, why do so many people think they are?

Because it serves the needs of two different groups. Scientists who are beleaguered today by creationists and by opponents of stem cell research like to dismiss religion as something that has been an eternal impediment to the progress of science. And the conservatives -- whether they're creationists or intelligent design theorists -- probably represent a majority in our society. But they also love to present themselves as martyrs. They're being oppressed by the secularists of the world. The secularists may only amount to about 10 percent of American society, but of course they do control many of the papers and the radio stations and TV stations of the country. So clearly these ideas serve some intellectual need of the parties involved, or they wouldn't persist, especially in the face of so much historical evidence to the contrary.

My sense is that you don't much like the stridency of certain atheists. The most obvious examples would be Richard Dawkins and Daniel Dennett.

Right. I don't know what the figures are right now, but I bet half of the scientists in America believe in some type of God. So I think Dawkins and Dennett are in a minority of evolutionists in saying that evolution is atheistic. I also think it does a terrible disservice to public policy in the United States.

So even if they believe that, you're saying, politically, it's a real mistake for them to link atheism to evolution?

Yes. Because in the United States, our public schools are supposed to be religiously neutral. If evolution is in fact inherently atheistic, we probably shouldn't be teaching it in the schools. And that makes it very difficult when you have some prominent people like Dawkins, who's a well-credentialed biologist, saying, "It really is atheistic." He could undercut -- not because he wants to -- but he could undercut the ability of American schools to teach evolution.

Dawkins himself acknowledges that, politically, this is not the smartest thing to do. But he says there is a higher principle at stake, and it's really the war between supernaturalism and naturalism. He says that's the real fight he's waging.

But you have to be careful. In the United States, the 90 percent who are theists far outnumber the 10 percent who are nontheists. So you want to remember that you are a minority, and that you need to get along, so some compromise might be in order. I'm not suggesting that he should compromise his own views. But by arguing not only that the implications of evolution for him are atheistic but that evolution is inherently atheistic is a risky thing.

So far, the rejection of evolution seems to be a predominantly Christian movement. Do we see much of this in other religious traditions?

We are now. It was mostly a Christian tradition, although to a certain extent, the reason we didn't see this in other religious cultures is because it was so dormant. Most modern Muslims weren't accepting evolution, but they weren't coming out in opposition to it. Most ultra-Orthodox Jews didn't accept evolution, but they didn't see any reason to say anything about scientific evolution. Today -- especially in the last decade or two -- we're seeing anti-evolutionism erupt in these non-Christian cultures. It's very big in the Muslim culture. The center for that is in Turkey, and the leader goes by the pen name Harun Yahya. His work circulates in millions of copies. They're translated into virtually every language [spoken by] Muslims.

Are we going to see this war between evolutionism and creationism continue for years to come?

I probably shouldn't even try to answer that question. Historians generally shouldn't try to be prophets. But it doesn't seem to be declining in any way right now. I think the creation scientists are still extremely strong. Some people say the intelligent design movement has eclipsed the creation scientists. But I think that's judging strength by press coverage. And the press will cover it only when it's exciting, when there's a legislative battle or a court case. I'm shocked by how much publicity the intelligent design movement has gotten in 15 years. They have a very good public relations machinery. So you have a handful of people in Seattle at the Discovery Institute and a few million dollars a year to play with, and they've convinced Time, Newsweek and others that the whole scientific community is divided over intelligent design. It's amazing!

Shares