If modern spycraft reached its zenith in the Cold War, it was born during World War II -- well, in literary mythology at least. Novels like William Boyd's recent, gripping "Restless" describe the meticulous training of British undercover agents, in particular a Russian imigri named Eva Delectorskaya, in the proper methods of following a mark, evading a shadow, setting up a letter drop or a safe house and, most important of all, ditching any operation the minute it starts to look a teensy bit off. As a result, Eva survives not only a rigged rendezvous (based on a real incident on the Dutch-German border in 1939) with a pair of Nazi generals pretending to be up for betraying Hitler, but she even manages to evade her own spymaster when he turns out to be a double agent. A contemporary story line about Eva's daughter, who learns her mother's true history only as an adult, conveys that the cost of the spy's life is an eternal, itchy paranoia that turns out to be contagious; pretty soon the daughter is wondering if everyone she knows has a secret identity.

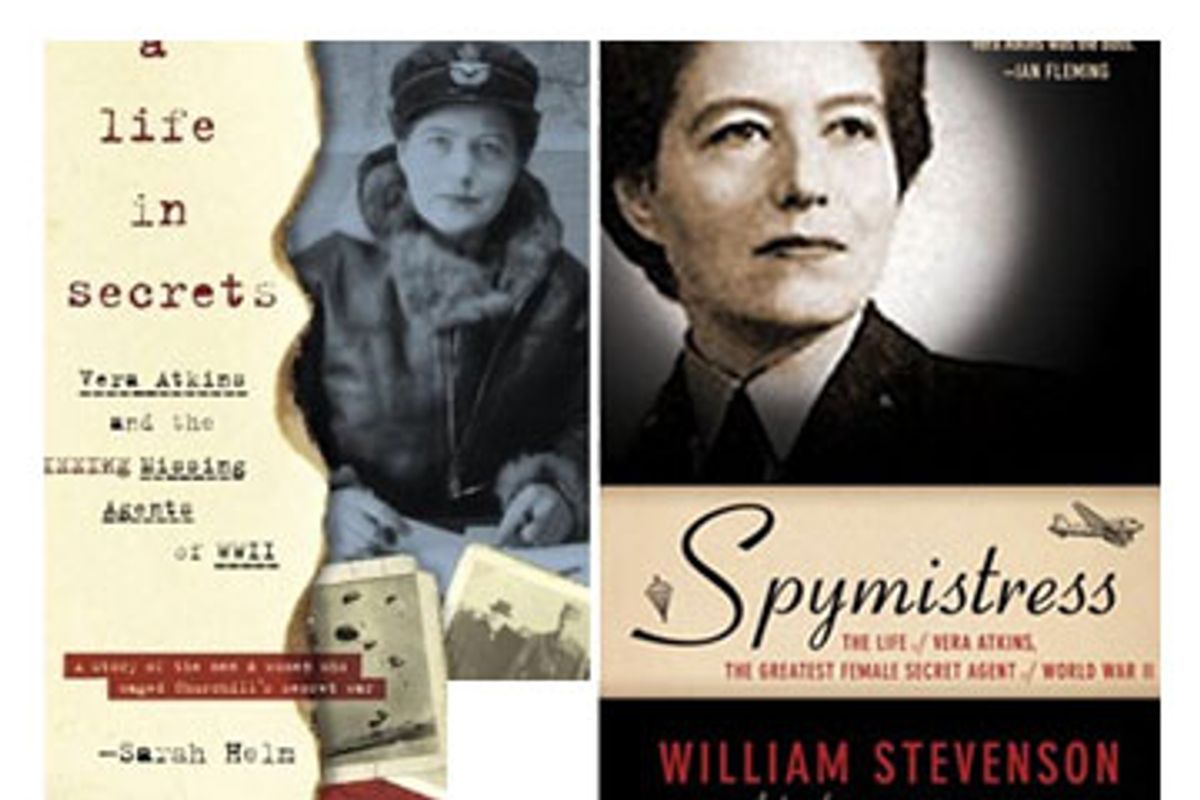

The life of Vera Atkins, a woman who helped run Britain's Special Operations Executive during the war, is every bit as fascinating and shot through with ambiguity as a spy novel. The version of it told by journalist Sarah Helm in "A Life in Secrets: Vera Atkins and the Missing Agents of WWII" is, on top of that, also a detective yarn in which the author treks to remote Carpathian villages and nibbles beet salad with ancient, decommissioned Romanian princesses in crumbling Soviet apartment blocks as she tries to nail down some of the more elusive facts. But Atkins' story has less in common with an intricate John Le Carré or Alan Furst novel than it does with the latest newspaper report about CIA screw-ups.

Atkins worked her way up from secretary to deputy and finally to head of Special Operations Executive F, the division of SOE in charge of developing, coordinating and arming the resistance movement in France. She recruited and oversaw the training of agents -- some of them women -- who were parachuted into Nazi-occupied France to that end. Perhaps the most spectacularly successful of these was Pearl Witherington, a courier who reorganized her circuit (a small, cell-like group of agents) when its leader was captured and led 1,500 Maquis guerrilla fighters against the German army on D-Day. Legend has it that the Nazis put a million-franc bounty on Witherington's head.

Not all of SOE's record was glorious, though, and that is the story that Helm prefers to tell. It's one of the factors that sets her book far above another recent treatment of Atkins' life, "Spymistress: The Life of Vera Atkins, the Greatest Female Secret Agent of World War II" by William Stevenson. Stevenson has made a profession of peddling old-school stories of espionage derring-do in which comparisons and connections to James Bond fly thick and fast -- he also wrote "A Man Called Intrepid" about the British intelligence head who (confusingly) almost shares his name, Sir William Stephenson. "Spymistress" insinuates that Ian Fleming, the creator of Bond, was one of Atkins' agents (in fact, he worked for naval intelligence) and provides frequent quotations from the author, despite the fact that he appears to have had no significant role in Atkins' life. Helm, by contrast, never even mentions Fleming.

Stevenson knew Atkins (Helm met her once) and several other figures in the British espionage scene, but this does not work to his advantage. "Spymistress" is mostly just clubby, name-dropping palaver about politics, power brokers and celebrities in mid-20th-century Britain and Europe, with Atkins' own name parachuted in every now and then to make it seem as if Stevenson is actually writing a book about her instead of showing off his "insider" dish. Stevenson also writes espionage fiction, and wanting to seem up-to-date on all the backstage gossip is a fatal weakness of spy groupies. In this case, a veteran journalist like Helm -- who has written for British newspapers for 20 years -- tells a much more enthralling story than the thriller writer.

That story involves two familiar, if depressing, recurring themes from real-life espionage history: blunders and turf wars. SOE -- set up by Winston Churchill on the eve of the war -- was always regarded by Britain's Secret Intelligence Service (SIS, but better known as MI6) as a rival. The organization was, as more than one observer and participant characterized it, staffed by amateurs. Some, like Atkins, were remarkably talented individuals who because of their outsider status might not have otherwise found a way to contribute to the "secret war." Others, like Atkins' immediate superior, Maurice Buckmaster, a former public-relations head for the Ford Motor Co. in France, were socially acceptable to British elites but disastrously ill-equipped to run agents into the most perilous parts of occupied Europe.

What interests Helm most about Atkins was what she did after the war, in the confusion that prevailed in Europe once the Nazi regime collapsed. Atkins committed herself, with indefatigable determination, to finding out what happened to 118 SOE agents who had not returned to Britain. In a few cases, as with the much-celebrated Odette Sansome, an SOE courier, those agents survived horrendous ordeals, and turned up sans passports and other identification, after escaping from their German captors. Many, however, died in Nazi prisons and concentration camps, and Atkins made it her cause to track down as much hard information as possible about their fates and to make sure that their service was properly honored.

Hers was a surprisingly unpopular mission. Charles de Gaulle didn't like the idea because he wanted his own people, the Free French Forces, to get sole credit for resisting the Nazi occupation. The head of SOE's security directorate thought that the investigation was too sensitive to be conducted by someone with a relatively low security clearance and not firmly under his own control. Various British authorities objected to Atkins' suggestion that the names of missing agents be circulated among the Allies, the Red Cross and other entities operating in the area because to do so would be to publicly admit that they had sent young British women on such dangerous missions. Unlike the male secret agents, few of the women carried military commissions, and were therefore not entitled to the protections guaranteed to prisoners of war.

Perhaps there were other reasons, too, namely the role of SOE bungling in allowing the agents to be caught in the first place. While Atkins was beginning her investigation, her former boss, Buckmaster, was taking a victory lap through liberated France, a bit of self-aggrandizement that would eventually backfire. Already, uncomfortable facts about F Section operations were circulating. One former agent dragged an SOE staff captain to a room in Paris that had been used as a Gestapo interrogation chamber and pointed to blood stains on the wall. He berated her about "how stupid everyone at HQ had been; how they had risked agents' lives. He said he had done everything to warn London that he was captured, but nobody had noticed."

At issue were wireless transmissions, the main vehicle by which SOE circuits in occupied territory communicated with the agency's London office. The messages were supposed to include both a false or "bluff" security check and a "true check" as a way to guarantee that the wireless operator had not been arrested and forced to send them by his or her German captors. London, however, didn't seem to take its own system seriously, and on more than one occasion, when a captured agent sent what ought to have been a tip-off message including only the bluff check, they got responses along the lines of "My dear fellow, you only left us a week ago. On your first message you go and forget to put your true check."

Again and again, irregular and suspicious wireless transmissions were dismissed as ordinary mistakes by Buckmaster, who apparently partook of the typical P.R. man's chronic optimism and belief that if you ignore bad things they might just go away. As a result, SOE continued to drop supplies and personnel directly into the waiting hands of the Germans. "I was amazed," said one captive agent, "at HQ Gestapo to see the quantities of British food, guns, ammunition, explosives that they had at their disposal." When SOE parachuted in a pair of new circuit heads, the Germans were able to replace them with impersonators (since none of the operatives in country had met the men yet) and use them to round up even more agents.

Finally, on D-Day, SOE received a transmission from one of the captured agents' radios reading, "Many thanks large deliveries arms and ammunition have greatly appreciated good tips concerning intentions and plans." It was signed by the Gestapo. A little later a message from another radio said much the same thing, adding that "certain of the agents had had to be shot" but others were cooperating. (Atkins later learned that Hitler himself had authorized the messages, as a morale breaker.) Buckmaster, bizarrely, took the time to write mocking replies. As Helm tells it, he never fully came to terms with his own role in delivering some of the brave men and women who worked for him into enemy hands, and in later life became almost delusional on the subject, blaming MI6.

Beyond the contaminated wireless operators, however, the SOE was significantly compromised by a double agent named Henri Diricourt, alias Gilbert, who probably betrayed as many of their people as the radio screw-ups did. Suspicions about Diricourt and his dealings with a shady SOE senior staff officer named Nicholas Bodington had been in the air even before the end of the war, but it was only Atkins' investigations into the fates of her lost agents that definitively established his guilt. She claimed to have always suspected Diricourt but said that the men of SOE were so dazzled by his alpha-male charisma they ignored her reservations. So Diricourt was naturally a topic of interest when Atkins interviewed Hans Josef Kieffer, who ran the German counterintelligence office in Paris where many of the SOE agents were imprisoned before being sent to Germany, just before he was hanged in 1947. "You are asking me if there was a traitor in your ranks?" he said. "But why are you asking me? ... Well, I think you know. Of course you know. It was Henri Diricourt."

Helm details the methodical way Atkins traced often sketchy leads and eyewitness reports to substantiate just how the missing SOE agents died and who killed them. She went to concentration camps, interviewed survivors and sat in on war crimes tribunals, joining the ranks of the first to learn of the extent of Nazi atrocities. She succeeded in unearthing "night and fog" executions (so called by the Nazis because the victims were supposed to vanish from the face of the earth) and learned of the often gruesome deaths of men and women she knew personally and usually saw off as they boarded the planes taking them to France. Four of the women she traced were burned, possibly while drugged but still alive, at the Natzweiler-Struthof camp in Alsace.

Helm gives particular attention to the case of Noor Inayat Khan, a Sufi of royal descent whose fate proved particularly difficult to trace, and with whom, she believes, Atkins had a special bond. (Just before Khan boarded the plane for France, Atkins took off the brooch she was wearing and gave it to her when the girl admired it.) A beautiful, almost otherworldly young woman who studied music and wrote children's books, Khan struck some SOE officials as too sensitive for the job. She nevertheless showed exceptional courage both before and after she was arrested, and even shamed one captured male agent -- who was rather comfortably situated in Kieffer's headquarters -- into attempting an escape. After being moved from prison to prison and kept in shackles, she died at Dachau, shot in the head after a savage beating; her last word was "liberti." Atkins was instrumental in securing for Khan the George Cross, Britain's supreme civilian decoration for courage.

No one could fail to be moved by either the horror or the gallantry in the truth Atkins uncovered, yet if one image of her emerges from all the accounts of those who knew her, it was of a woman who rarely expressed deep emotion. Some of the surviving family members of her agents seem to have disliked her for this alone; others have been persuaded by a conspiracy theory arguing that Buckmaster deliberately allowed the agents to be captured because they had been implanted with false information to mislead the Germans. Even the many people who liked and loved Vera Atkins describe her as "cagey" and self-controlled. Yet if she was as "cold" as her critics complained, why was she so dogged, even against her own interests, in investigating her agents' fates?

Even more nagging is the question of why Atkins, by every account an exceptionally competent, intelligent woman with a phenomenal memory, did so little to bring to account the very people who put her agents in harm's way? If she felt responsible for Khan and all the rest, as many of Helm's sources maintain, if she had a keen enough sense of justice to hunt down the Germans responsible for their suffering and to do her part in seeing them punished, why not the SOE leaders and the traitor known as Gilbert? Henri Diricourt, astonishingly enough, walked away from a postwar military tribunal scot-free, largely because no one from SOE showed up with the evidence to convict him. (He is said to have died in the crash of a small plane -- filled with gold he intended to trade for opium -- over Laos in 1962.)

Helm finds the answers in Atkins' past, the details of which the spymistress strenuously endeavored to conceal from most of the people she knew and everyone she worked with. Although she presented herself as "more English than the English," she was in fact a Romanian-born Jew, the privileged daughter of a family, the Rosenbergs, that had made and lost a couple of fortunes in Russia, Eastern Europe and South Africa. Her mother's side of the family was heavily Anglicized, and her father's people were assimilated Germans and Catholic converts; her cousin Fritz and his wife only managed to escape Romania when he showed fascist guards that he was uncircumcised.

As a woman, a Jew and an enemy foreign national, Atkins was hardly suitable SOE material on paper. Her origins, despite her efforts to obscure them, were known to many, and anti-Semitism lay behind much of the suspicion she encountered in high places, as Helm amply demonstrates. During her tenure at SOE, Atkins was struggling hard to become a naturalized British citizen, a tall order at that time, and one of her most important sponsors and patrons was Buckmaster. (Conceivably, she might have been thrown out of the country entirely had she aggravated the wrong people, although she probably had too many connections for that.) In later years, she devoted herself more to the celebration of SOE's true heroes than to the exposure of its incompetence and frauds.

Helm also discovers another likely cause for Atkins' extreme caution and loyalty toward Buckmaster. One of the chief attractions of "A Life in Secrets" is the book's dual story line, one describing both Atkins' investigations and Helm's prodigious research. In a late chapter that exemplifies biographical diligence, Helm follows a series of hazy leads, including an interview with a very elderly and intermittently senile lady, to dig out persuasive evidence that in 1940, Atkins made a hazardous journey to the Netherlands, at one point hiding for days in a barn. Her goal was to deliver a large sum of money to an official in German military intelligence in order to secure a new "Aryanized" passport for her cousin Fritz, thereby saving his life. Had anyone in Britain discovered that she had bribed a member of the Abwehr, she would never have worked for the government again. This, Helm, believes, is a major source of the chronic secrecy, the caginess, for which Atkins was famous.

The final image of Atkins that emerges from Helm's superb biography is of a woman compelled by history, prejudice and circumstances into a position in which compromise was the only option. It was surely enough to turn anyone into a sphinx. In the end, the virtue that Atkins chose to stick with was loyalty -- to Buckmaster and the SOE, perhaps ignominiously, but also to her unquestionably valiant agents. In a life full of evasions and concessions, it was the one pure star she found to steer by. "They were her 'bairns,' if you will," said a Scottish colleague who had started out resenting Atkins and wound up respecting her. "And after all, she knew she had sent them to their deaths."

Shares