"Transgender": Does even the word confuse you? If you were asked to define it, could you?

If not, you're hardly alone. For years, the transgender community has existed in the shadow of the gay, lesbian and bisexual rights movement -- though most trans-people agree that redefining their gender has little to do with their sexual orientation. The word is applied to everyone from drag queens and sex reassignment surgery patients to femme gay men and butch straight girls. And these days, when discussions of transgender do happen, it's usually in the context of the sex industry or debates about unisex bathrooms and gender-blind hallways in college dormitories. With such boundless, cloudy meanings, is it any surprise that even the most sex-savvy, gay-friendly, politically correct among us still have a hard time explaining the term?

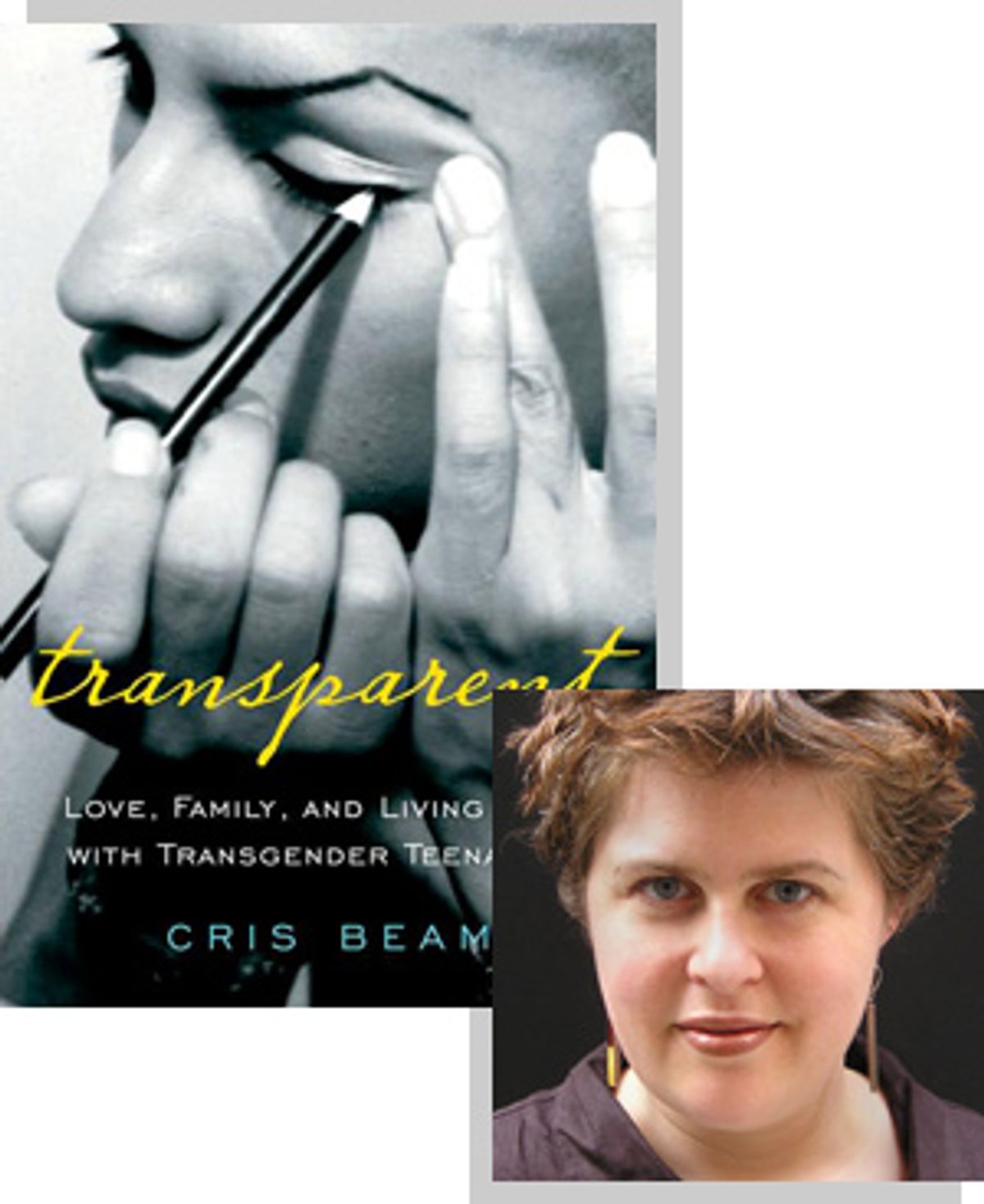

Cris Beam, the author of "Transparent: Love, Family, and Living the T with Transgender Teenagers," hopes her new book will help take on some of the mysteries and misconceptions that still haunt the transgender community. Beam, now 34, moved to Los Angeles in 1997, while her girlfriend attended graduate school. Lonely in her new city, she became intrigued by Eagles, a local high school specifically for gay and transgender kids; with the time left over in her freelance writing schedule, she began to work there as a volunteer. During the two and a half years Beam taught at Eagles, she discovered a complex but marginalized tribe of transgender teens who had nowhere to go but the streets. "Transparent" chronicles those stories, and describes how, within a few years, Beam found herself deeply involved in the kids' lives, entangled in their dreams, disappointments and their search for the truth about themselves and their gender.

Weaving personal narratives with the history of sex changes and the dynamics of the black-market hormone industry, "Transparent" is anchored by the wildly unstable lives of four trans-women -- Christina, Domineque, Foxxjazell and Ariel, all of whom were Beam's students at Eagles. Beam's tale gives equal weight to Foxx's blinky-eyed aspirations to be a pop star and her struggles with her incarcerated, physically abusive boyfriend. She shuttles through Domineque's flurry of foster homes and past Ariel's heavily medicated mother, and speaks frankly about their loves, friends and mentors.

But the character Beam describes in the most searing detail is Christina, the young woman who later became the author's foster daughter. Blurring sociological research and personal experience, Beam stares down the teenager's manic highs and homeless, motherless, loveless lows. The result is a meticulous document of a subculture clamoring to be heard, and a revelation of how a sense of community and family may be the prime determinant of one's fate.

Salon sat down with Beam in New York to talk about prostitution and RuPaul, the importance of family and teenage identity, and whether America is ready for its first transgender rapper.

What was your first day like at Eagles?

The day I showed up, the people in charge -- the "office managers" -- said, "Um, can you teach?" and then they ran off. They threw me in a classroom with about eight kids. Nobody was watching them: Some were dancing in the corner and somebody else was asleep on the floor. For some reason, I said without thinking, "Do you guys want to make a magazine?" And they started gathering around, kind of interested, asking me, "What kind of magazine?" We started by talking about fashion. I really liked the kids, so I just kept coming back, and I ended up staying for two and a half years.

What kinds of kids did you meet?

The school was really just a catch-all for gay or trans street kids. There wasn't a whole lot of education going on. The population was very transient -- the kids who really wanted an education went elsewhere. The kids came there because they were homeless and had heard about it, and they would come in to get help, or they had truancy tickets and needed the cops off their back, or had been beaten up or harassed at their other schools -- a whole host of reasons. Some of them had grown up in L.A. their whole lives, but many others had traveled there from someplace else.

Why were the kids attracted to L.A.?

It's a big city -- and if you're a queer of any kind, you tend to want to go to the city, because that's where the freaks are, and maybe you can blend in. But there are reasons why L.A. is specifically attractive. Transgender kids hear rumors about hormone availability. Because they're smuggled up from Tijuana, there's a big black market based in Los Angeles. In Mexico, hormones are sold over the counter. They can be perfectly safe, but the kids want to take a lot for fast results.

They also hear that there are trans-people in L.A., and about this community of older trans-kids that "adopt" the newcomers on the street. They teach the new ones how to survive in the streets and pass as women and attract men, make friends, and sometimes even how to pick a corner to hustle. Some people just want to be stars, so there's that hope that they'd be discovered in Hollywood.

Before you met the students, what kind of preconceived notions did you have about the "transgender" community?

I hadn't known a whole lot of transgender people before -- or, at least, I didn't know it if I did. When I went to college at U.C. Santa Cruz, it was a very stridently lesbian time. You know, "womyn" with a "y," and all sorts of identity politics around women's-only space. That meant that trans-women were kept out. I also didn't know that trans people could be as young as they were, that they could be as young as 12, 13. I was really clueless, and I had been sort of blinded to the real struggles since I had come of age in Santa Cruz, where it was really discriminatory toward trans-women.

You write that most people imagine that all transgender people are drag queens, like Ru Paul, but that that stereotype is not necessarily accurate. Is that how you thought of trans-people before coming to Eagles?

Growing up in the gay community in the San Francisco Bay Area, I thought it was about performance. At that time, you were starting to see trans-people on shows like Jerry Springer. And it was always really awful, disparaging stuff -- full of "your girlfriend's really a man" imagery. At Eagles I saw a much broader spectrum, and I was really amazed at, and impressed by, the way these kids were offered a kind of freedom with regard to what it meant to be a boy or a girl. In a sad way, because they were off the radar of so many social services, they weren't getting helped, and so they had so little to lose. But they were liberated in a way that kids from other socioeconomic classes weren't.

Before I started this project, I thought the word "transgender" meant that a person didn't feel like the gender they were biologically born into. But trans-girls can be tomboys, trans-boys can be feminine. Trans-girls and -boys can be gay.

At the same time, some of the kids you met did strive for that stereotypical, glam-queen look. Why do you think that imagery is still so appealing to some trans-kids?

It's true -- there were some kids that were very performative and wanted to act like pop stars. At that time, the Spice Girls, Christina Aguilera, Britney Spears, Beyoncé were all really big. Of course, kids are idolizing pop stars in every high school in America. But when you're not socialized female, when you're not raised as a little girl, you don't have internal models for how to be a girl. Your mom isn't saying, "Here, sweetie, try on these earrings, have these cute little shoes." When you're socialized as a boy, you're often taught to idolize women in a really extreme way. So, if you're transgendered, sometimes you want to become that extreme woman who has been idolized.

But, again, a lot of the kids weren't that way. Many were very mellow, very understated. They just wore jeans, baby T's and sneakers, and passed perfectly well. There was a huge range.

You write that the teen transgender world is not without categories. What do you mean?

When you're a kid -- but especially as a street kid -- there is social pressure to "pass" [as a specific gender]. Trans-kids create these categories to create order in their world. There is a certain amount of freedom -- you can be a woman with a penis and that's fine, and you can call it your "pussy stick" -- but there's also a real pressure to conform to standards of beauty. Because they are young and insecure and want to fit in, they really freak out when they see someone that looks unpassable, or "clockable," which means easily spotted as transgender. They want everyone to look like a highly feminine version of themselves.

Your research focused on a very specific group of kids who had been kicked out of their homes and turned to prostitution and drugs. Are you anxious about how the rest of the transgender community will react to the book?

I had a lot of fears about this book coming out because I was afraid that the trans community would say, "You only show the dark side. What about the transgender neuroscientists and the transgender airline pilots?" Whenever you write about a community, especially one that doesn't get a lot of attention, you're always under fire to be representative of the whole group. In this case, I only wrote about a few kids, one of them being my foster daughter. It's a narrow study. Yet those lives are the reality for many kids, because there's so much trans-phobia and so much pain. A lot of transgender kids end up on the street, because there aren't any economic possibilities for them, so they turn to prostitution. When they're prostituting, they get picked up and put into foster care, then they're thrown into group homes. When they're in the homes, they're housed according to their birth gender. So you have trans-girls living with the boys, and there's always drama. They feel violated or misunderstood, they run away, they're back on the street, and they need money -- and the whole cycle starts again.

You seem to see a deep connection between family life and the fate of the transgender street kids. Can you explain that a bit?

Of the kids I got to know, the kids that ended up OK all had good parents. You can say that the homelessness, the drugs and the prostitution were a result of the kids being trans, but what I ended up finding was that the ones who were able to pull through were those who had really strong early childhood support. Those who didn't do so well were often fundamentally unloved -- long before they even came out as transgender. It's easy to point fingers and say that the trans community is enmeshed in sex work and whatever. But it originates with how willing families were to support kids and understand what transgender or transsexual really means.

Speaking of which, I think for many people, those terms themselves can be very confusing. Can you explain the difference between intersex and transgender, and between post-op and pre-op?

Intersex is where your physical reproductive organs do not match your gender state, where there is some sort of chromosomal or genital anomaly from birth. Being transsexual or transgender is where you feel like your internal sense of self doesn't match your external gender characteristics. Some people argue that the state of being transgender is actually being neurologically intersex -- but that stuff is tricky territory because the study of that kind of neurology is in its infancy.

You're preoperative [pre-op] if you haven't had sex reassignment surgery, and post-op if you have -- usually referring to genital reconstruction, or a mastectomy for a trans-man. Pre-op and post-op are difficult terms because they imply that gender is a continuum and that post-op is an automatically desired state. A lot of trans-people don't like that term, because it implies you're not "done" if you're pre-op, when some people don't feel that surgery is something they need.

Is there a disconnect between the intersex and transgender community?

It's different for everyone, but some intersex people feel like, "My state's biological. I was born this way and I can't help it, whereas transgender people are choosing this." But some transsexuals are like, "Well, I didn't choose this, I was born like this too!" There may be tension there, but there's also a lot of room for collaboration between the two, because we're all imprisoned by this idea that you have to be male or female, and many, many people don't fit -- whether for reasons that are physical or spiritual or psychological.

Do you sense tension between the transgender and the mainstream gay community too?

The "T" [transgender] has been readily added on to the GLB [gay, lesbian, bisexual] moniker in the past few years. But yes, a lot of gay people still really don't understand transgender, and there does seem to be a fear among gay people that the trans community could bring the gay movement down.

Right now there's an effort to normalize gays, to say, "We are just like you, we want marriage rights, job protection." And as the gay community makes political gains, the fear is that the trans community will look too weird. A lot of trans-people feel that the gay community has shunned them and said, "Not you guys, not yet. Let us get our rights, and then maybe you can come along." Also, being gay and being transgender are different issues. Gender identity and sexual desire are really separate tracks -- who you want to be with vs. who you identify as. Yet they're lumped together under the same umbrella called "queer."

You say that the most thriving, activist transgender communities are found in small liberal arts colleges like Smith and Wesleyan. But those communities really have no interaction, or maybe even knowledge, of the world you write about. Do you think their political activism can have an affect on kids like those at Eagles?

I would love to see the two come together more. When I go to transgender conferences, they are highly academic, concerned with language and representation and all that. It feels like they're speaking a completely different language from what's happening on the streets. They're not talking about the fact that kids [who can't afford breast implants] are shooting silicone directly into their bodies and dying, or that they're taking overdoses of hormones they buy on the black market or getting AIDS from prostitution. I think what academia does is important work, too. They're changing the hearts and minds of people who have power and influence, and that's going to filter its way down. But I would like to see more cross-pollination between the two communities, a little more attention being paid to HIV risk, issues of homelessness, violence on the street, drug use, and not just theoretical issues.

One of the teenagers in your book, Foxx, dreams of being a successful transgender rapper. Realistically, do you think our culture is ready to embrace someone like her?

Actually, Foxx is about to shoot her first music video! She called me the other day and was like, "Girl, I'm gonna be on 'Click' on Logo," MTV's gay network. And there's a gay rapper, Deadlee, who's doing a tour called the "Homorevolution" that is scheduled to launch in March 2007.

It's hard for me to gauge what America is ready for. I go from L.A. to New York to San Francisco, so I feel isolated in urban bubbles where Foxx's stardom seems possible. But I'd love to think it's possible. ABC just put a transgender character on "All My Children" -- which made me think, "If daytime soaps, which I think of as a pretty conservative bastion, can do it, maybe kids could welcome it."

You write about being troubled by the thin line between transgender people engaged in destructive behavior, and those who work in the outreach to combat that destructive behavior. Can you explain how you saw that dynamic at work?

Well, for instance, kids who do drug outreach are often just over drugs themselves or still using drugs. I found that there's a thin line between helpers and the people who seek help. I think that's because there are not many work opportunities for transgender young people, so they tend to stay in the transgender community. Sometimes they do really want to help -- they've just gotten over whatever difficulty they've been in. They have the fervor of the newly converted, and they want to help other young people get through trouble. But it's not enough, really.

How could outreach be improved?

I'd like medical professionals to be more involved, because there are teens who are morphing their own bodies with very dangerous techniques. Doctors need to monitor these kids -- if they're going to do it anyway, why not make sure they aren't taking copious amounts of hormones? We also need trained therapists to give them the psychological support to make decisions. And we need people to do longitudinal studies, too. Nobody's looking at, for example, what the breast cancer risks are for somebody taking so much estrogen. Right now we are just putting out fires and handing out condoms, which is hard work but not good enough.

Shares