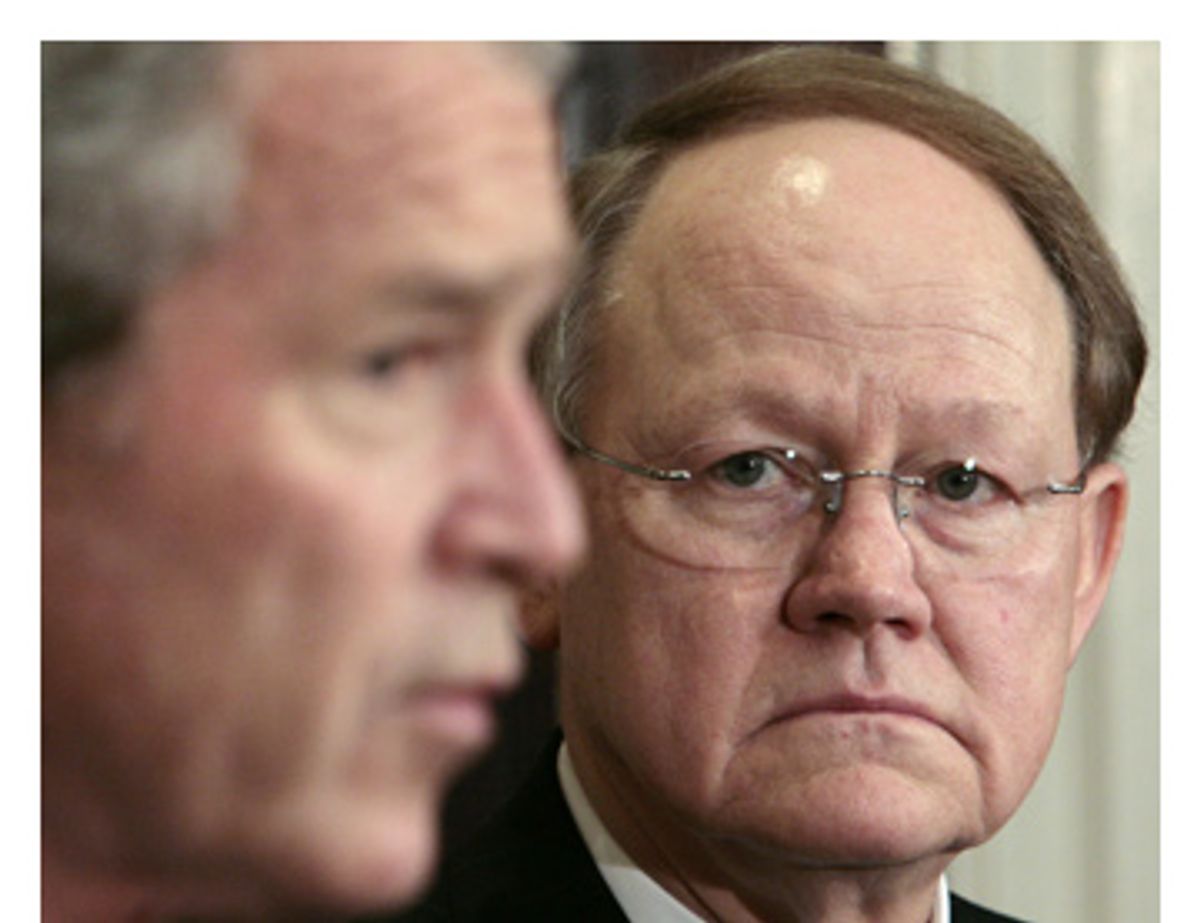

The Bush administration's choice last week of J. Michael McConnell to be director of national intelligence is a major blunder -- and not just because the man who will be overseeing 16 different spy agencies, including the CIA, took the job after a "personal approach" from an old friend named Dick Cheney.

The problem is with McConnell's résumé. At present, U.S. intelligence is more dependent on private contractors than it has ever been. About half of the rapidly expanding annual intelligence budget, or more than $20 billion, now goes to outside firms. The work those private contractors perform has been slammed repeatedly for mismanagement, privacy violations and bias -- and yet the would-be head of the nation's intelligence effort is a top executive at one of the worst offenders. McConnell, a retired vice admiral and former director of the National Security Agency, is the current director of defense programs at Booz Allen Hamilton.

With revenues of $3.7 billion in 2005, Booz Allen is one of the nation's biggest defense and intelligence contractors. Under McConnell's watch, Booz Allen has been deeply involved in some of the most controversial counterterrorism programs the Bush administration has run, including the infamous Total Information Awareness data-mining scheme. As a key contractor and advisor to the NSA, Booz Allen is almost certainly participating in the agency's warrantless surveillance of the telephone calls and e-mails of American citizens.

If the Democrats now running the House and Senate intelligence committees do their job right, they could learn a great deal about these programs and the instrumental role contractors are playing in U.S. intelligence during McConnell's confirmation hearings. McConnell should be compelled to answer some tough questions before the Democrats even consider confirming him.

The intelligence community's reliance on outsourcing dates back to the late 1990s, when commercial advances in computer software and communications began to outpace the considerable lead U.S. intelligence once had in encryption and other technologies. These shortcomings were particularly acute at the NSA, which suffered a system-wide computer blackout in 2000 that shut down the agency's global listening and surveillance system for more than two days, reducing the contents of the president's Daily Briefing by more than 30 percent. In response, during the waning days of the Clinton era, the highly secretive agency had opened its doors to contractors.

The privatization of intelligence within the NSA accelerated as soon as the Bush administration took office. And then came 9-11. The attacks served as a hiring catalyst for other agencies -- like the CIA and the Pentagon, which found themselves short of analysts, linguists and other specialists -- to follow the NSA's lead. Rather than take on new employees, intelligence agencies and counterterrorism centers sought out companies that, like Booz Allen, had hundreds of employees with security clearances on their staff -- clearances nearly always earned during prior and less lucrative employment with the federal government.

Since 2001, intelligence spending has risen about 40 percent a year, and contracting has ballooned by about that much. In some agencies, contractors make up the majority of employees. At the Pentagon's highly classified Counterintelligence Field Activity office, which has been strongly criticized in Congress for spying on U.S. antiwar protesters, 70 percent of the workforce are contractors.

U.S. intelligence budgets are classified, as are nearly all intelligence contracts. But the overall budget is generally understood to be running about $45 billion a year. Based on interviews I've done for an upcoming book, I estimate that about 50 percent of this spending goes directly to private companies. This is big business: The accumulated spending on intelligence since 2002 is much higher than the total of $33 billion the Bush administration paid to Bechtel, Halliburton and other large corporations for reconstruction projects in Iraq.

Booz Allen, along with Science Applications International Corp., General Dynamics, Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman, CACI International and a few other corporations, is one of the dominant players in intelligence contracting. Among its largest customers are the NSA, which monitors foreign and domestic communications, and the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, an amalgamation of the imagery divisions of the CIA and the Pentagon that was established in 2003.

A few years ago, Information Week reported that Booz Allen had more than 1,000 former intelligence officers on its staff. Asked to confirm that number last month, company spokesman George Farrar told me: "It is certainly possible, but as a privately held corporation we consider that information to be proprietary and do not disclose."

Buried deep on the company's Web site, however, I recently found an explanation of a Booz Allen I.T. contract with the Defense Intelligence Agency, which carries out intelligence for the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the secretary of defense. It states that the Booz Allen team "employs more than 10,000 TS/SCI cleared personnel." TS/SCI stands for top secret-sensitive compartmentalized intelligence, the highest possible security ratings. This would make Booz Allen one of the largest employers of cleared personnel in the United States.

Among the many former spooks on Booz Allen's payroll are R. James Woolsey, the well-known neoconservative and former CIA director; Joan Dempsey, the former chief of staff to CIA Director George Tenet and recently executive director of the President's Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board; and Keith Hall, the former director of the National Reconnaissance Office, the super-secret organization that oversees the nation's spy satellites.

For his part, McConnell was head of the National Security Agency from 1992 to 1996. Prior to that he was the chief intelligence officer for Colin Powell at the Joint Chiefs of Staff during the first Gulf War, where he worked closely with Dick Cheney. On Friday, McConnell told the New York Times that his work at Booz Allen had allowed him to "stay focused on national security and intelligence communities as a strategist and as a consultant. Therefore, in many respects, I never left." That is an understatement. As a senior vice president at Booz Allen, McConnell is in charge of the firm's assignments in military intelligence and information operations for the Department of Defense. In that work, his official biography states, McConnell has provided intelligence support to "the US Unified Combatant Commanders, the Director of National Intelligence Agencies, and the Military Service Intelligence Directors."

And in a relationship that has been completely missed in media coverage of his appointment, McConnell is the chairman of the Intelligence and National Security Alliance, the primary business association of NSA and CIA contractors. As INSA chairman, I've been told, McConnell is presiding over an initiative to enhance ties between the intelligence agencies and their contractors and domestic law enforcement agencies.

McConnell has said little publicly about what he thinks of the administration he will be serving or of that administration's policies. In an off-the-record address to an intelligence conference last year, however, McConnell did say that on the issue of domestic spying, he might be "a little more liberal" than the administration. "Any bureaucracy -- NSA, CIA, FBI, you name it -- can do evil," he concluded. "My view is, you have to have oversight."

McConnell is certainly right on that point. Many intelligence analysts believe that congressional oversight during the Bush administration has been virtually nonexistent. Despite the administration's flagrant abuse of U.S. laws concerning privacy and NSA wiretaps of U.S. citizens, the Republican majority did very little to investigate its abuses.

Now there is a new Congress that actually believes in oversight. One intelligence program that should merit its attention, and that members might want to ask McConnell about during his confirmation hearings, is Total Information Awareness, a data-mining project run by former National Security Advisor John Poindexter that was outlawed by Congress in 2003. Between 1997 and 2002, according to a recent report by the American Civil Liberties Union, Booz Allen was awarded more than $63 million worth of TIA contracts. Last Friday, Newsweek reported that McConnell was a "key figure" in making Booz Allen, along with SAIC, the prime contractors on the project.

Shortly after the 9/11 terrorist attacks, Booz Allen was hired by the CIA to audit the agency's monitoring of trillions of dollars in international financial transactions moving through a European cooperative called SWIFT. The company's impartiality to monitor this program was questioned last year by a European Union panel, which recommended independent supervision and declared that "we don't see such independent supervision under the current situation, and this must be established."

The ACLU and Privacy International, an organization that monitors government intrusion, jointly issued a scathing report on the issue last September. "Though Booz Allen's role is to verify that the access to the SWIFT data is not abused, its relationship with the US government calls its objectivity significantly into question," the two organizations said.

Booz Allen rejected the charge. "What clients are buying from us is independence and objectivity," spokeswoman Marie Lerch told the New York Times. But the company's close ties to the intelligence community through its employment of former high-ranking officials calls that objectivity into question.

Another key area that Congress should examine is Booz Allen's relationship with the NSA. Largely through McConnell, Booz Allen has very close ties to the NSA, once considered so secret its initials were said to stand for "No Such Agency."

Booz Allen served as the NSA's chief advisor on one of its most significant outsourcing projects. Called Groundbreaker, this huge project was launched shortly before the 9/11 attacks to overhaul the NSA's internal I.T. systems. Booz Allen's work on this project was outlined in a Booz Allen magazine piece on "Government Clients." Working with the NSA, the article states, Booz Allen "helped create a new model of managed competition that outsourced key pieces of the agency's IT infrastructure services." Its work on Groundbreaker "included source selection support and evaluating vendor proposals."

Last year, however, the Baltimore Sun investigated the project and concluded it was a failure. Over the course of the project, Groundbreaker's $2 billion price tag had doubled, and the problems with the system, according to insiders who spoke to the Sun, were legion. "Some analysts and managers have said their productivity is half of what it used to be because the new system requires them to perform many more steps to accomplish what a few keystrokes used to," the paper reported. Another NSA program that Booz Allen was involved in, Trailblazer, which was designed to overhaul the NSA's signals intelligence system, is widely considered an even worse failure.

Booz Allen's involvement with both projects would have directly involved the company in the NSA's surveillance of U.S. domestic communications under what President Bush calls the "Terrorist Surveillance Program." Although Bush claims that the NSA program is so narrow that the agency is only listening to calls where an al-Qaida operative is at the other end, longtime analysts of the NSA believe that the program is much bigger than it has been portrayed. "I think they're listening to everybody," says John Pike of GlobalSecurity.org, a highly respected defense research organization.

When the Groundbreaker and Trailblazer problems came to light, the Senate suspended the NSA's independent acquisition authority. In July 2006, the oversight subcommittee of the House intelligence committee issued a blistering critique of the Pentagon's management of the NSA and other intelligence programs. "Many of the major acquisition programs at the National Reconnaissance Office, the National Security Agency and the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency have cost taxpayers billions of dollars in cost overruns and schedule delays," the bipartisan report concluded. Booz Allen was deeply involved in all three, and as head of the firm's defense intelligence programs, McConnell would have had direct participation.

Contracting has now become so ubiquitous in intelligence that the DNI itself is complaining. "Increasingly, the IC [intelligence community] finds itself in competition with its contractors for our own employees," the DNI wrote in an unclassified report on personnel policies released last June. "[T]hose same contractors recruit our own employees, already cleared and trained at government expense, and then 'lease' them back to us at considerably greater expense."

Concomitant with this report, the DNI launched its first study of intelligence contracting. The results, however, won't be in until the end of this fiscal year. By then, McConnell will probably be firmly ensconced as the director of DNI. Getting a grip on these problems is too much to ask of a contractor who was himself deeply involved in them.

Shares