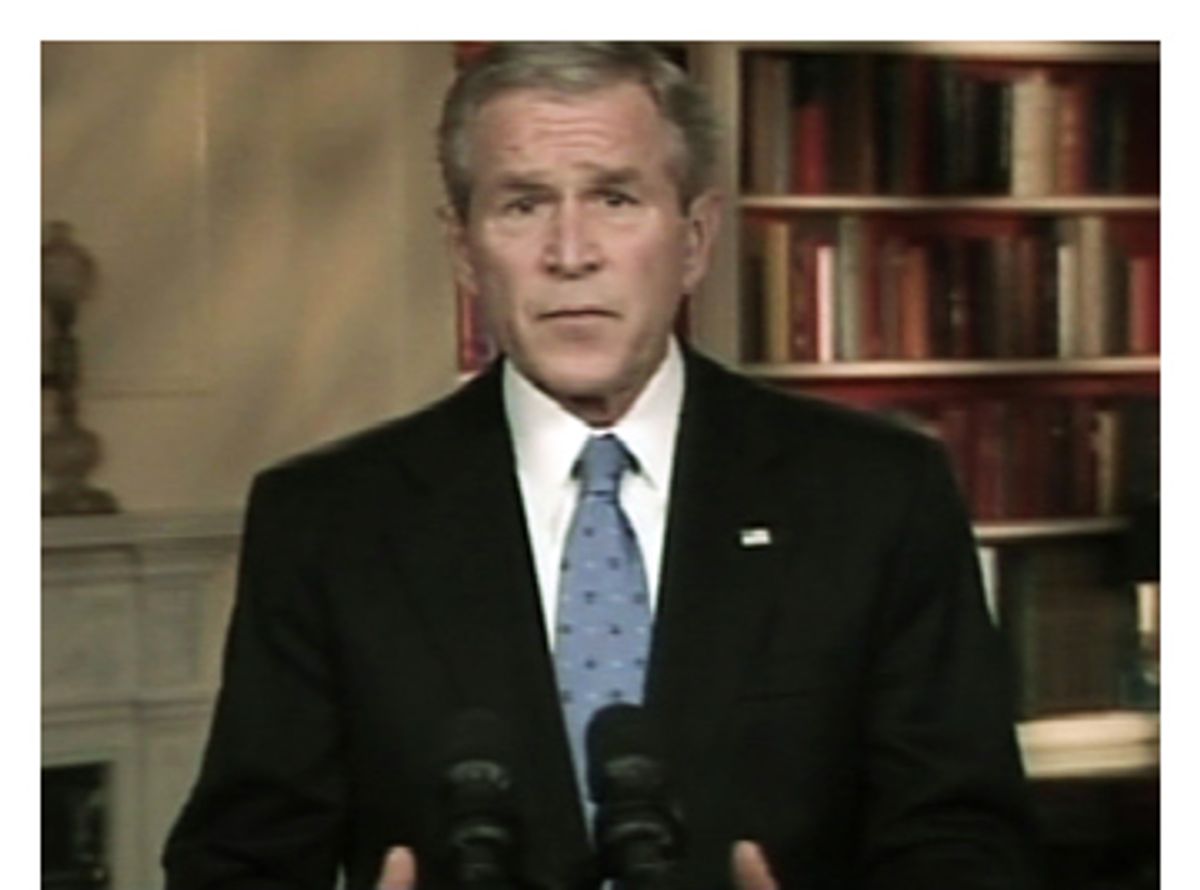

Throughout the long century to come, any future leader contemplating sending American troops into combat should carefully watch a tape of George W. Bush's speech to the nation Wednesday night -- and ponder its underlying lessons. This was Bush deflated, his arrogance temporarily placed in a blind trust, looking grayer than ever with his brow furrowed with lines of worry. How humiliating for Bush to be forced to say with a stony face, "The situation in Iraq is unacceptable to the American people -- and it is unacceptable to me."

This is what happens to a commander in chief when his vision of victory becomes a struggle for survival, when confident talk of a slam dunk on the way in is replaced by a clamor to slam the door on the way out. This is what happens to a president who is losing a war -- and who is reduced to begging for more time, another chance, to set things right.

Little more than a year ago, Bush unveiled what was then billed as his "Strategy for Victory in Iraq." Speaking to the midshipmen at the Naval Academy in late November 2005, the president declared in a confident tone, "Coalition and Iraqi security forces are on the offensive against the enemy, cleaning out areas controlled by the terrorists and Saddam loyalists, leaving Iraqi forces to hold territory taken from the enemy, and following up with targeted reconstruction to help Iraqis rebuild their lives."

As a portrait of reality, that ranks up there with "Brownie, you're doing a heck of a job." Suffice it to say that a limited number -- a very limited number -- of Iraqis have been able to rebuild their lives. Bush himself said Wednesday night with uncharacteristic albeit belated honesty, "The violence in Iraq, particularly in Baghdad, overwhelmed the political gains the Iraqis had made."

Anytime a president commands network prime time for a White House address, it is a political moment, even if Bush himself is immune from the direct wrath of the voters. Yet it is misleading to look at the strategy behind the Iraq speech in traditional Republicans-versus-Democrats terms. Bush was speaking to a far narrower audience than the nation at large. The situation in Iraq is too dire for the president to dream of converting Democrats or even independent voters to the cause of staying the course. Bush was playing to the only constituency he has left -- the Republican base.

Even at a time when GOP incumbents who face difficult 2008 reelection fights have become militant critics of escalation (Sens. Gordon Smith, of Oregon, and Norm Coleman, of Minnesota, are two), Bush still commands the personal loyalty of much of his party despite the deepening Mesopotamian morass. All the major presidential contenders (Rudy Giuliani, Mitt Romney and, of course, John McCain) bowed to heavy pressure from the White House not to dissent too audibly in their public comments about Bush's speech and plan for a troop surge.

The White House knows the limitations of the powers of Congress in wartime, even with legislators as aroused as the incoming Democrats. Virtually all congressional attempts to force Bush to change his strategy in Iraq would be vulnerable to a presidential veto, which could be overridden only by a two-thirds vote of both houses of Congress. As long as the president holds on to his Republican base in Congress -- plus Joe Lieberman, who was pointedly singled out in the speech -- he can continue to run the war his way.

But it is clear that Bush understands at this stage in the war that even loyal Republican voters need convincing. A revealing moment in the speech came when Bush stepped out of character and tried to address the inherent skepticism of his audience: "Many listening tonight will ask why this effort will succeed when previous operations to secure Baghdad did not." The president's answers were weak, such as when he claimed, "This time, we will have the force levels we need to hold the areas that have been cleared." Few military experts -- outside of perhaps the geopolitical strategists at Fox News and neoconservative think tanks -- believe that Bush's plan to deploy 21,000 more soldiers in Baghdad and Anbar province will do the job. Even Bush sounded tentative on this score when he began a sentence, "Even if our new strategy works exactly as planned..."

Ever since Bush denounced the theretofore unknown "Axis of Evil" in his 2002 State of the Union Address, at a moment when the nation was still fixated on the horrors of Sept. 11, it has been instructive to listen for new rhetorical gambits in major presidential speeches. That is why it is possible that the most fateful words that Bush uttered from the White House library on Wednesday night were these: "Iran is providing material support for attacks on American troops. We will disrupt the attacks on our forces. We will interrupt the flow of support from Iran and Syria."

Even though the Democrats have won the rhetorical war in labeling the Bush war plan as escalation, 21,000 additional troops is pretty small potatoes by the standards of prior wars such as Vietnam. But expanding the battlefield to the borders of Iran and Syria -- if that was indeed what Bush was suggesting -- now that would qualify as escalation, as even Henry Kissinger might admit.

Bush may well have bought himself a little more room for maneuver in Iraq with his attempt at donning sackcloth and ashes. But trapped in an abysmal situation largely of his own making, it is worth wondering what Bush's own secret exit plan might be. Is his latest speech -- and the troop surge -- a last show of muscular resolve before Bush bows to political reality and the willful ineptitude of the Maliki government and reluctantly sets a timetable for withdrawal? Or will Bush's last-desperation gambit be a wider war that touches Iran and Syria? Either way, it is a cautionary reminder of what happens when you go to war with the president you've got rather than the president you'd like to have.

Shares