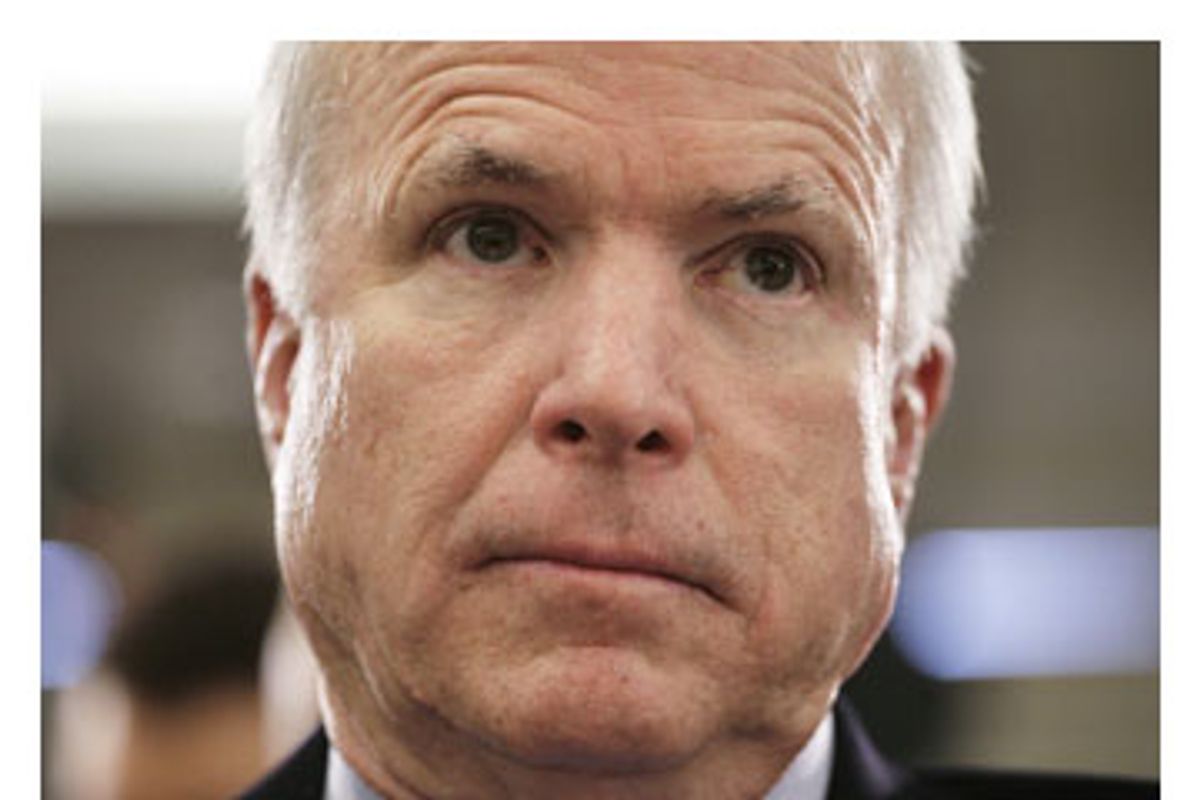

When Sen. John McCain appeared last October at the British Conservative Party conference as the presumptive next president of the United States, the stars seemed fixed in the firmament for him. The myth of McCain appeared as invincible as ever. His war story -- a bomber pilot shot down over North Vietnam in 1967, held as prisoner for five years and tortured -- is the basis of his legend as morally courageous, authentic, unwavering in his convictions, an independent reformer willing to take on the reactionaries of his own party, an "American maverick," as he calls himself in his campaign autobiography. The titles of his books reflect the image: "Character Is Destiny," "Why Courage Matters" and "Faith of My Fathers." Defeat at the hands of George W. Bush in the battle for the Republican nomination in 2000, in which he was subjected to dirty tricks as he traveled the signs of his cross in his "Straight Talk Express," solidified his canonization. Members of the press corps so venerated him that he called them "my base."

McCain's political colleagues, however, know another side of the action hero -- a volatile man with a hair-trigger temper, who shouted at Sen. Ted Kennedy on the Senate floor to "shut up," called his fellow Republican senators "shithead," "fucking jerk," "asshole," and joked in 1998 at a Republican fundraiser about the teenage daughter of President Clinton, "Do you know why Chelsea Clinton is so ugly? Because Janet Reno is her father." As recently as a few months ago, McCain suddenly rushed up to a friend of mine, a prominent Washington attorney, at a social event, and threatened to beat him up because he represented a client McCain happened to dislike, and then, just as suddenly, profusely and tearfully apologized.

Within the Republican Party nearly everyone who has had serious dealings with McCain distrusts him (including traditional Republican moderates, not just conservatives). While taking right-wing positions on social issues like abortion and gay marriage, his simmering resentment of Bush led him to virtually caucus with the Democrats in early 2001 (before Sept. 11), using the Democratic Leadership Council as his back channel. Then, abruptly, he rushed to embrace Bush.

McCain's political advisors believe that though he would easily be elected president in 2008 if he captured the nomination, he might not get the nomination. In 2000, McCain did not win a primary state where the voting was restricted only to Republicans. So McCain decided to let the general election take care of itself as he won over the party faithful. He campaigned enthusiastically for Bush in 2004. He sought to reconcile with the religious right, whose leaders he had called "agents of intolerance" in 2000, speaking on May 13, 2006, at the Rev. Jerry Falwell's Liberty University, and hiring its debate coach as a communications aide.

McCain had belatedly taken the lead in opposing Bush's torture policy, an issue that could not be more personal for him. But after the Supreme Court last year declared Bush's secret tribunals for detainees and use of extreme interrogation techniques illegal, Bush sought congressional approval of his revised version of the program. At first, McCain fought Bush, but the right attacked him, in a campaign some of his advisors said they had reason to believe Karl Rove had whipped up. McCain quickly capitulated, even agreeing to suspension of habeas corpus. McCain, as someone close to him explained to me, figured he could continue to play the issue when he became chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee in the next Congress. Asked about the chance the Democrats might take control, McCain declared, "I think I'd just commit suicide."

As the neoconservatives abandoned Bush's sinking ship, McCain welcomed them aboard. "McCain began reading The Weekly Standard and conferring with its editors, particularly Bill Kristol," the New Republic magazine reported. And he hired a board member of the neocon Project for the New American Century, Randy Scheunemann, as his foreign policy aide.

McCain positioned himself as consistently belligerent, even to Bush's right: in favor of bombing Iran and North Korea. He also proposed a "surge" of troops into Iraq, an idea gleaned from the neocons. If Bush adopted the Iraq Study Group's approach of diplomacy and redeployment, which McCain assailed as "dispiriting," the right would hail McCain as a prophet with honor. Unfortunately, McCain's strategy depended on Bush's not adopting his proposal. Importuned by the same neocons who had sold it to McCain, Bush seized upon the "surge."

McCain had trapped himself. And he has finally succeeded in chaining himself to Bush. As Bush's war has escalated, McCain's popularity has nose-dived. Still the front-runner for the Republican nomination, he might have made himself more acceptable to the base, but his political strategy has shattered his own myth. Bearing the burden of Bush he may have become unelectable.

Shares