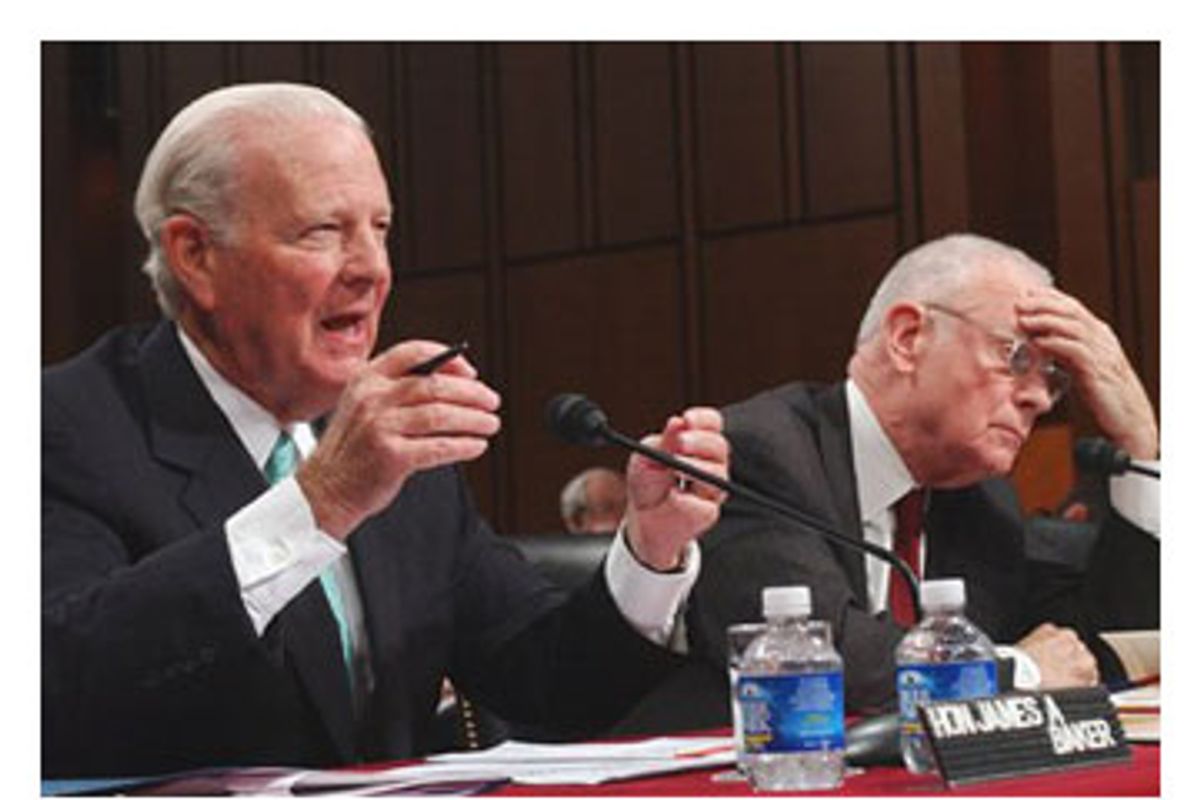

Eight weeks ago, Bush family consigliere and former Secretary of State James Baker led the establishment's revolt against the Iraq war when he presented the devastating indictment by the Iraq Study Group, which declared flatly, "The situation in Iraq is grave and deteriorating." Tuesday afternoon Baker was back in the same Capitol Hill hearing room, wearing the same green tie (or its close cousin) -- but this time the suave septuagenarian was the only defender of George W. Bush's troop surge in a roomful of skeptical senators.

"The president's plan ought to be given a chance," Baker told the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. "The general [David Petraeus] you confirmed 81-0 just the day before yesterday, this is his idea. He's a supporter of it. He's now the commander on the ground in Iraq. Give it a chance." Baker repeated his refrain so often that it sounded like he was channeling some perverse version of a John Lennon tune: "Give Escalation a Chance."

It was one scene in another all-day Iraq drama on Capitol Hill. What Baker's appearance illustrated is how hard it still is for Republicans who have sway with the White House to pressure Bush publicly. Meanwhile, legal scholars who appeared before the committee suggested that Congress does have power to take action over the war, if it so chooses. Yet, listening to the Democrats, it was evident that they are still searching for a mechanism with which to effectively challenge Bush on the war.

Former Democratic Rep. Lee Hamilton, who co-chaired the Iraq Study Group with Baker, responded with a mournful chorus when asked at the hearing what had changed since the group's report was released in early December. As Hamilton put it, "December was the deadliest month of the year ... Saddam Hussein's execution made him a martyr in the Arab world. Oil production is still down to prewar levels ... And the end of the year has passed and the Iraqi government still has not met any of [its] benchmarks."

Hamilton, rather than Baker, reflects the current mood on Capitol Hill, where almost no one is following White House talking points anymore. In retrospect, the Iraq Study Group report was a historic document that, along with the 2006 elections, triggered a mass political retreat on the war. Now, even Republicans don't sound very different from House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, who declared at a press conference Tuesday on returning from a trip to Iraq, "In a matter of months, one way or another, we must begin the redeployment of our troops."

Sen. Arlen Specter, who headed the Judiciary Committee for two years before the Democrats took control, took his cue from the rising congressional opposition to Bush's surge plan. "I would respectfully suggest to the president that he is not the sole decider," Specter said. "The decider is a joint and shared responsibility." But despite the sound bite, Specter later admitted to reporters that he hadn't decided whether to support any resolution on Iraq next week when the issue comes to the Senate floor.

For his part, Baker's determined public effort to give the president the benefit of every doubt, while still embracing the Iraq Study Group's call for a phased redeployment, was a masterly example of lawyerly doublespeak. He stubbornly insisted that the president had endorsed many of the recommendations of the Iraq Study Group, while glossing over the big picture -- both the escalation, and the White House's refusal to negotiate with Iran and Syria.

The problem that baffles almost everyone is how to change course in the face of a recalcitrant administration. Non-binding resolutions, such as the anti-surge statement slated to be debated on the Senate floor next week, are just that -- symbolic gestures that may shape public opinion but cannot pierce the White House bunker.

Wisconsin Sen. Russ Feingold announced at the start of the hearing Tuesday that he would offer legislation Wednesday to cut off funding for the war after six months. But Feingold admitted to reporters, "I haven't gotten hearings on this yet. But this is not something that's going to happen through hearings. The Iraq situation is getting worse and worse." He seemed to be acknowledging that his remedy may still be too extreme to win a hearing, let alone command a congressional majority to defund the war.

To buttress his cause, Feingold had assembled an ideological cross section of constitutional lawyers to discuss the legal powers of Congress in the face of an unpopular and ill-conceived war. Despite the White House's trumpeting of an overarching interpretation of the president's war powers as commander in chief, the consensus among both liberal and conservative legal scholars at the hearing was that Congress does possess war-ending powers if it chooses to assert them. As Bradford Berenson, who served on Bush's White House legal staff during the president's first term, declared, "I do think that the constitutional scene does give Congress broad authority to terminate a war."

What was telling during the hearing, however, was how much power Congress has ceded to the president since it passed the war resolution in October 2002. Illinois Democratic Sen. Dick Durbin won scant support from the legal scholars for his theory that the 2002 Iraq resolution may now be legally invalid because there were no weapons of mass destruction and Saddam Hussein has been executed. Rather, the contrary seemed to be the case -- Congress had implicitly endorsed the war every time it passed military appropriations without any conditions attached.

Walter Dellinger, a leading liberal legal theorist who had been assistant attorney general in the Clinton administration, regretfully acknowledged that Bush has the legal power to expand the war into Iran under the guise of protecting U.S. troops in Iraq. As he put it, "The resolution of 2002 is quite broad and quite broadly worded ... It is not geographically limited." Dellinger hinted that his preferred remedy on this point would be to rewrite the Iraq resolution to explicitly rule out military operations against Iran. It was reminiscent of the way Congress banned military operations in Cambodia in the 1970s, even as it was toothless in its efforts to end the war in Vietnam itself.

For all the easy talk of a confrontation between Congress and the White House over Iraq, it remains unclear whether most legislators want to move beyond anguished speeches about the war. There is no easy mechanism for Congress to change the U.S. mission in Iraq -- legislation would collide with the president's veto, and, as Feingold signaled, there is still a widespread unwillingness to tamper with military appropriations. As a result, Congress is floundering about, trapped in the Capitol Hill version of "No Exit."

Shares