Our strategy in Iraq has long been based on training homegrown security forces there; in the formulation of the president, "As the Iraqis stand up, we will stand down." But what happens if the Iraqi soldiers and police we stand up have their own agenda, not that of a unified Iraq but that of the sectarian militias that are tearing apart the country, and especially of Muqtada al-Sadr, the radical Shiite cleric who controls the powerful Mahdi Army? According to some observers, including Tom Lasseter, a reporter for the McClatchy chain of newspapers, that's what's happening.

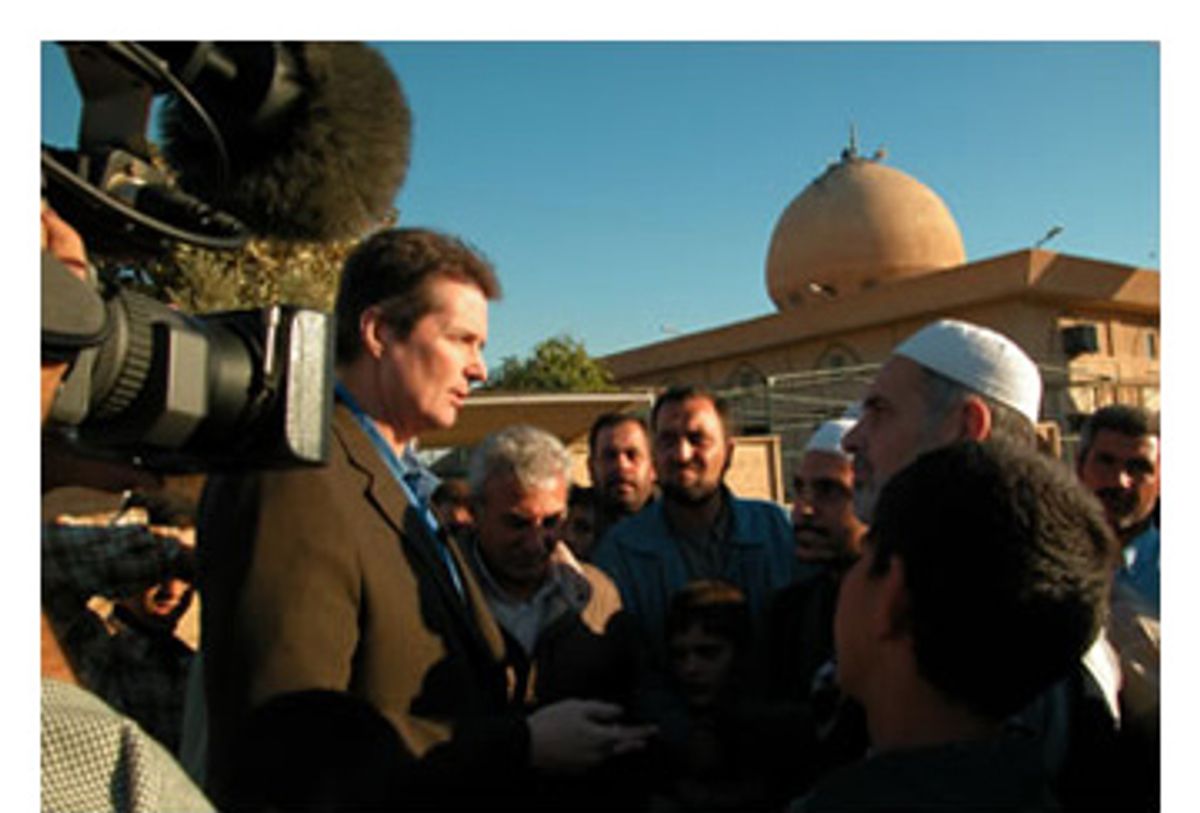

Martin Smith has seen the situation up close. In more than 30 years working for ABC News, for PBS's "Frontline" and for his own independent production company, RAIN media, Smith has won every major television journalism award, including the Emmy and the Alfred I. duPont. "Gangs of Iraq," an episode of an upcoming PBS series of documentaries called "America at a Crossroads," which will debut in April, is his fourth movie about the country since the U.S. invasion. It looks at the influence of militias in the country, and how that has hampered the U.S. effort to raise and train functional Iraqi army and police forces. Some of the scenes show just how serious the infiltration of militia and sectarian influence has been -- one, for example, depicts Shiite Iraqi soldiers, on a raid with their American trainers, realizing that a bigger arms cache than the one they've found is held by a Shiite cleric to whom they are loyal. The Iraqi soldiers don't tell their American allies.

Salon spoke with Smith on Feb. 2.

What's the extent of Mahdi Army sympathy or involvement, within the Iraqi army, that you saw while you were in Iraq?

Well, it's all anecdotal because there's no scientific measure of this, but if you talk to commanders, whether they're American advisors to the police or to the army, or if you talk to Iraqi commanders, they'll all tell you it's a problem. And you see it most graphically in [U.S. commanders'] refusal to inform the Iraqis of the missions they're going on. When they're going out with the Army, the Iraqis are not informed as to where they are going. In [one case] they were told they were going away for several days so they wouldn't even suspect that the raid was [to occur] less than a mile away from the base.

We were with the police on some routine patrolling, and before the patrol set out, the American in charge, the American who was embedded with the Iraqi police team, frisked all of the policemen, looking for cellphones. And when we asked him why he had to do that, he said, "Because they could call up their friends in the militias" -- he was talking about the Mahdi Army in this particular case -- "and inform them as to our whereabouts and that we're coming to this place or that place." So that's kind of the sum of what we saw.

Did you get the sense that what the U.S. is doing is essentially training the Mahdi Army?

We're not training the Mahdi Army by intent, but we're providing training for people who may take our training program and then go join the militias. This is another problem that we found, and again the American commanders can tell you this; there's no good accounting system. When police -- and I should add that the problem is greater in the police than it is in the army -- [graduate] from the training program, [the trainers] don't have a good way to monitor where they go after that. Because the police go into small villages or into a neighborhood, there's no effective system set up for figuring out if they in fact after training go and rejoin their regional [police] units. [U.S. and Iraqi authorities] know, in fact, that some of them don't. As early as August '04, there are photographs of uniformed Iraqi police celebrating with the Mahdi Army after a battle in Najaf. Starting in April '04, with the first assault on Fallujah, a battalion refused to go fight; they told their American commander that they didn't sign up to fight other Iraqis.

There's a disturbing scene in your film, in which Iraqi soldiers go on a raid with U.S. troops and you catch the Iraqi soldiers talking about how the weapons they found are "child's play," not a real arms cache. Can you describe that scene?

We went in on this raid with the Iraqi army in Mahmoudiya, which is in the so-called triangle of death south of Baghdad. We were going into a Shiite neighborhood, and we were told, although the Iraqi army wasn't told, that we were going to raid what they call a "JAM cache," a Jaish al-Mahdi, or Mahdi Army, arms cache. When we got there, a cameraman and I, we were both filming; we didn't have an [Arabic] translator with us because our translator had not been able to join us because his brother had been kidnapped and tortured. So without a translator, we were just filming what we could. And it was pure instinct of Tim Grucza, the cameraman, to film these guys as they were muttering off to the side. We had no way of knowing what they were saying. And when we got back to the editing room here and we had it translated, we discovered that what [the Iraqi soldiers] were talking about, at this raid, was that the weapons the soldiers had collected were just "kids stuff," and that the real stuff was at [their cleric's] place. They muttered on about how this was just child's play or kids stuff, and they didn't tell the Americans anything about this. It clearly shows that they're not really pulling with their U.S. buddies.

The people who are joining the army and the police force, do they have another agenda for joining separate from helping to create a secure Iraqi state?

In the case of the police force after the January 2005 elections, there were a number of firings of Sunni leaders in the Ministry of the Interior, and Badr Corps [the militia unit of the SCIRI, a Shiite political party] people were brought into leadership positions, and there was a definite sectarian taint for many police units. Whole units were brought in intact from the Badr militia, according to some accounts that we were told. How one goes out and establishes all of this is problematic, but there are numerous reports of whole units of Badr Corps coming intact into the ministry to work in the police forces.

In instances like that or in instances where there's Mahdi Army infiltration, are we arming the militias?

Well, that's the fear of one of the principal advisors of the Ministry of the Interior, who said that his greatest fear is that all we have been doing is training and equipping the Iraqis to fight a civil war. It certainly wasn't our intent to do that, but in practice people have received training who have then gone back and fought with their militia.

So do you think trying to "stand up" a national army at this point might be a futile effort?

It's the centerpiece of our policy, but as I've said, trying to get people to form a national police force in the middle of a civil war is a very difficult, if not impossible, task. It's like going into Kentucky during our Civil War and getting people from the North and the South. If you put them in a unit together, you expect them to fight together in the interests of what?

It's just hard to imagine how you train sectarianism out of people when the situation in the country is so insecure that people feel, legitimately, that they need a militia to protect their neighborhood. People don't trust, don't have faith, in a neutral army. The Sunnis fear it. It's a pretty discouraging situation, I'm sorry to say.

We have another scene in the documentary at the [police] training center in Jordan. Back in December [U.S. and Iraqi authorities] opened this massive training center in Jordan. They figured they couldn't open a police training center in Iraq because of safety issues, so they opened it in Jordan and they brought all these trainers in from all over the world. And we have these scenes of them trying to indoctrinate Iraqis with patriotism, with loyalty to the national entity, and to identify with Iraq and not first and foremost with their sect or their militia. I guess the only way to describe it is to say it's embarrassing at best to see this guy, kind of like a football coach, trying to get these people to pledge allegiance to their own flag. You have to see it to believe it.

When your documentary premieres, what do you want people to take away from it?

I just want them to understand why there's so much killing going on. I mean, we open the documentary, we're with some troops and we find a body on the streets of a Sunni neighborhood, presumably a Sunni man who was kidnapped. He has been mutilated, tortured, killed and dumped near a garbage pile, where we found him. We then have scenes at the morgue, scenes at a graveyard. That's the reality of Baghdad today, and that's where we begin -- with sort of wanton killing. So what we're trying to do is go back and try to understand why the killing continues, why the civil war [exists]. We do it through looking at the effort, which is the centerpiece of [U.S.] policy, to stand up the Iraqi troops, and how that has run squarely into the militia and sectarian problems, and how those troops that we've tried to train, and spent billions on -- I think $14 billion and counting -- have been infiltrated by militia, or by people with sectarian loyalties above national loyalties.

We're hearing a lot about a change in policy, but I don't understand what that change is. We're putting in 21,000 extra troops, perhaps, but the centerpiece of the policy remains training the Iraqis to run their own country and [then] getting out. Regardless of what we do in the meantime in terms of quelling some violence, securing and holding for a period of time certain neighborhoods, the fact of the matter is that the only way we [can] get out is either we turn around and walk out now or we continue to train and we get to a point where we think they can handle it, and we walk away. That's the centerpiece. So our documentary focuses on that training effort and what it has run into.

Shares