"The only thing I don't read much of now," wrote the Irish writer Nuala O'Faolain in her 1998 memoir, "Are You Somebody?" "are middle-range authors -- Kundera, say, or Paul Auster. Writers who play middle-level games." Middle-range sounds harsh, particularly as it veers perilously close to middlebrow -- though if I were a novelist I don't think I would mind being bracketed with Milan Kundera.

Yet, no matter how much pleasure I've derived from Auster's work -- which, with the publication of "Travels in the Scriptorium," includes 14 novels, seven volumes of memoirs and essays, poetry, screenplays for "Smoke" and "Blue in the Face" (set in his and my old Brooklyn neighborhood, Park Slope), not to mention, I'm told, a Madonna video that he directed -- I've only sometimes felt that the resolutions of his Chinese box fictions were as satisfying as I expected them to be while reading.

Then, a writer has the right to be judged from his best work, and Auster is so prolific that it's difficult to bring his entire oeuvre under one critical umbrella. I don't think I've ever met anyone who has read all his books, and among those who have read most of them there is often sharp division over which ones they think best. Those who love his enigmatic and convoluted "Moon Palace" (1989) usually don't care for his post-apocalyptic "In the Country of Lost Things" (1987); those who were delighted by the surprisingly straightforward, autobiographical "The Brooklyn Follies" (2005) don't seem to get "Timbuktu" (1999), his fable-like story told from a dog's point of view.

Auster's most popular novels are usually grouped under the amorphous label of metafiction; but phantasmagorical, I think, better applies to his most famous work, "The New York Trilogy" (1987), composed of three short novels, "City of Glass," "Ghosts" and "The Locked Room." The atmosphere of these books could be described as Kafka by way of Dashiell Hammett. (Hammett is an obvious Auster influence; the plot of "Oracle Night" [2004] was inspired by an anecdote in "The Maltese Falcon.") In these books Auster seemed to be on the verge of creating a new genre in which the classic detective story mated with the novel of postmodern urban angst.

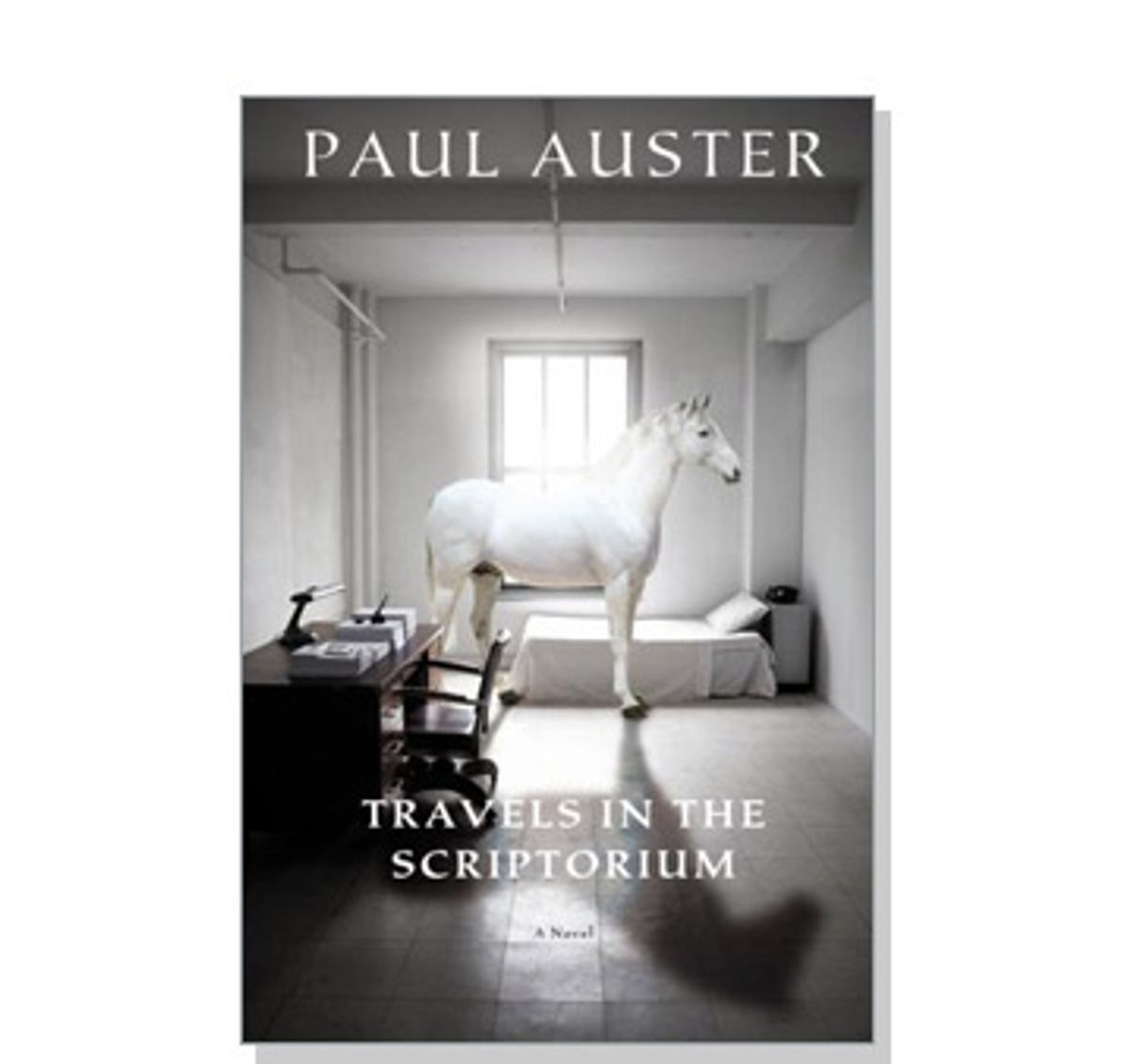

He is at his best when he's being playful -- that is, playing off other genres. When Auster gets cooking, he's like a magician who can amaze us by sawing a woman in half; when he's not, as in "Travels in the Scriptorium," it's as if he's sawing away without a woman in the box. The central character of "Travels," a Mr. Blank, sits in a sparsely furnished room staring at the walls, trying to summon clues about who he is and what has brought him there. (The few objects in the room are labeled with their names, suggestive of the "insomnia plague" that forces the villagers to hang signs on everything from clocks to cows in Gabriel García Márquez's Macondo in "One Hundred Yeas of Solitude.") Mr. Blank is reading a manuscript he may or may not have written about the near extermination of an aboriginal people (bringing to mind J.M. Coetzee's "Waiting for the Barbarians"). There is also a direct reference to a famous rocking-chair passage in Samuel Beckett's novel "Murphy."

About a third of the way through "Travels in the Scriptorium," you may get an odd sense that you're not reading a real novel -- or at least not a new novel. Surrounded by what appear to be allusions to his many influences, Mr. Blank is visited by numerous characters, including James P. Flood and Daniel Quinn, detectives from earlier Auster novels. In fact, all of Blank's visitors are characters from other Auster novels, most of them showing up to berate Mr. Blank for the way he has treated them. (I can't imagine why; I thought Auster was more than fair to most of them.) For those who enjoy this Russian doll-type mystery, "Travels in the Scriptorium" is a feast; the name of the author of the manuscript Mr. Blank is reading is John Trause, a character from Auster's "Oracle Night," and "Trause" is also an anagram for "Auster," who has sometimes used himself as a character in his fiction under his own name.

I fear I'm making "Travels in the Scriptorium" sound like more fun than it is; none of the characters come alive, and if it weren't for our memory of them in previous books, they'd have no identity at all. Those who aren't familiar with Auster's work may be mystified, while those who are may wonder why the characters are dragged back into service for no apparent reason. "Travels" seems less a case of "Several Characters in Search of an Author" than "One Author in Search of Himself Through His Characters." (If Auster's catalog didn't list more than 30 titles, one might suspect that "Travels" was an attempt to work himself through writer's block.)

The term "self-referential" hardly begins to describe "Travels in the Scriptorium." It's intricate, all right, and at times intriguing, but all of its puzzle parts add up to a picture of a perfect blank -- or is that the joke Auster was playing on us with his protagonist's name? Auster offers a solution of sorts to his puzzle, though none is wanted. Without wishing to tip the ending, the notion that the author is nothing without his characters is surely as wrongheaded an attitude for a writer as is possible. They're nothing without him. And the sooner Auster gets around to remembering that, the sooner he'll leave the middle-level games behind.

Shares