It's a poignant story, many times told. Immigrant family arrives in America, begins lifelong tug of war between assimilation and cultural identity, struggles to find a foothold on the economic ladder, establishes a flow of information, cash and visa sponsorships (and/or arranged marriages) between those left behind in the old country and those busily becoming citizens of the new.

Kids come home from school speaking English; parents answer in Spanish or Farsi or Cantonese. Parents eat menudo or lavash or jook for breakfast; kids slurp milk pinkened by Fruity Pebbles. Kids grow taller and more cynical than their parents, refuse to attend church or mosque or temple, leave home, marry or intermarry, serve as translators between their parents and their own kids during bilingual holiday dinners, and cobble together a patchwork culture, an often-uneasy union of their customs of origin with new, Americanized traditions of their own.

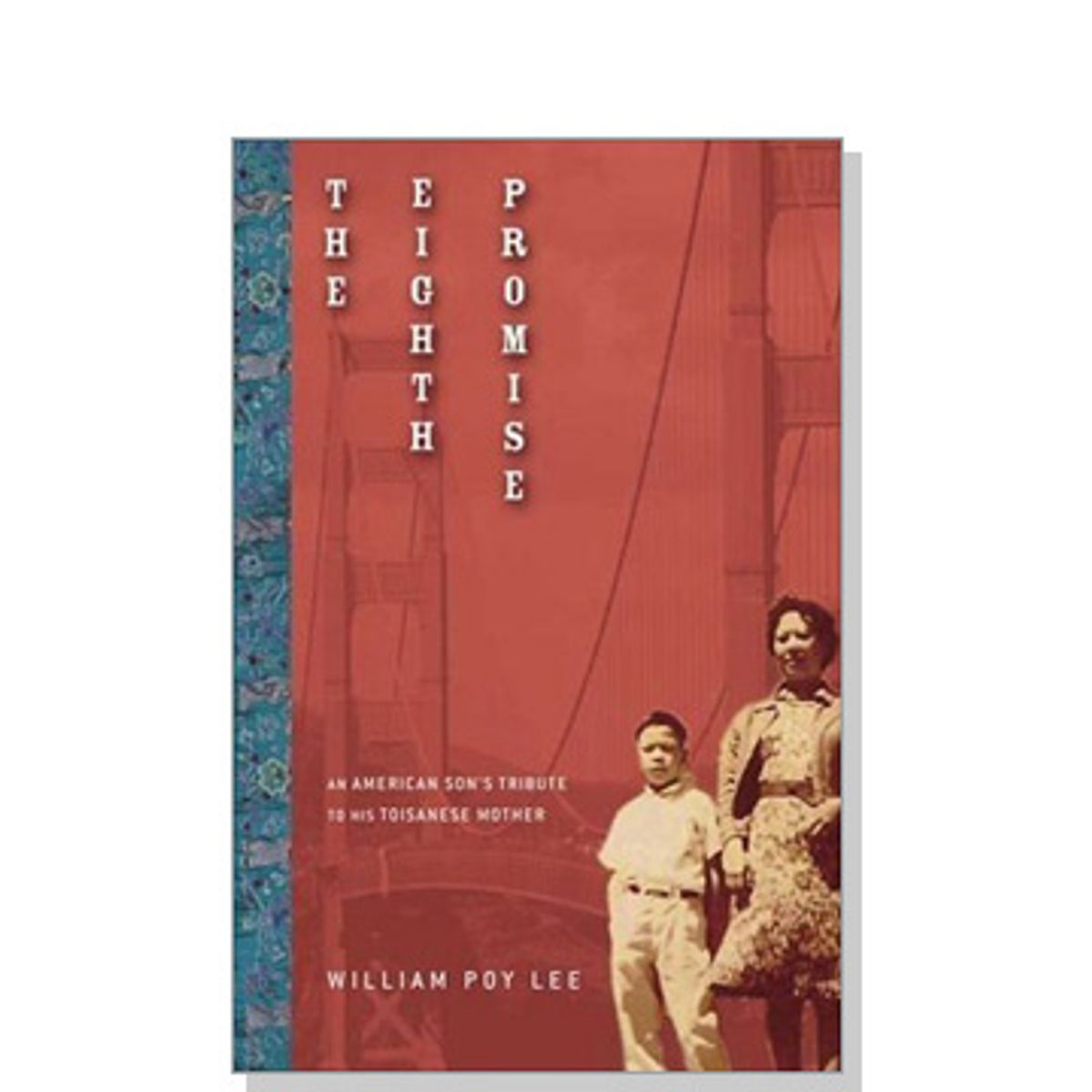

In "The Eighth Promise: An American Son's Tribute to His Toisanese Mother," William Poy Lee lends his family's coming-to-America story a fresh twist by structuring the book in an unusual way. In alternating chapters, Lee lets his mother's story come through in her own voice; her memories, and perspectives, taped by the author during a series of interviews, are juxtaposed with his, rendering lush and surprising what might otherwise be a somewhat predictable tale. In the tradition of the blockbuster multigenerational epic -- "Roots," "'Tis" and "Cane River" come to mind -- "The Eighth Promise" describes William Poy Lee's upbringing in, rebellion against, and ultimate return to the bosom of his family, community and culture.

The story begins in China in 1935. Lee's father, Fook Toon, was summoned from his hamlet to San Francisco's Chinatown by his father, a U.S. citizen, then sent back to Toisan, a village in China's Pearl River Delta, to pick a wife from the prospects selected for him by village "go-betweens." Fook Toon was 26, Poy Jen 21 in 1948 when their meeting and marriage were arranged with the support of Poy Jen's mother, who was determined to protect her favorite daughter from the ravages of the Chinese civil war by sending her to America. Before she left their village, Poy Jen was trained by her mother in the skills considered essential to every Toisanese woman, whether in Suey Wan or San Francisco: how to amend the soil, harvest bok choy at exactly the right moment, make medicinal chi (energy) soups and use these soups to treat all manner of emotional, physical, environmental and spiritual maladies.

Poy Jen's mother also instructs her daughter to keep the eight promises to which the book's title refers: to raise her children to be Chinese, to find suitable Chinese-American husbands for her sisters, to sponsor the emigration of her mother and two brothers to America, to keep alive in her children the dream of a democratic Nationalist China, to keep her children connected to the village of Suey Wan, to keep the Toisan clan alive in America, to cook chi soups for her family, and to raise her children to "live with compassion for all," as her mother raised her.

William Poy Lee, the first of Poy Jen's four children, was born in San Francisco in 1951. Following a stellar academic career that began in San Francisco's Chinatown public schools and culminated in his graduation from the University of California at Berkeley, Lee became an architect, and then a lawyer, and then chief legal officer of Bank of America. In the opening prologue he describes the "paralyzing, crackling, debris-filled" breakdown he experienced in his mid-40s. After spending several decades as an über-achiever in hot pursuit of the American dream, in 1995 he abruptly left his job, his girlfriend and his home. His life, a carefully constructed compromise between his parents' expectations and the activist awakening he experienced as a college student in the '60s and early '70s, came to a crashing halt.

"And that's when I completely opened up to my ancient past in another land and culture, China," Lee writes. "I slowly realized that I came from a wonderful beginning, even before I was born in San Francisco ... I am born of ancestors who were farmers and lived not as individuals or the mobile nuclear family unit, not even just as an extended family, but as a Clan [who] had lived and loved in one locale and harvested the same fields for a millennium or more ... How had I lost touch with those deeper places, spending an entire decade burying them with the shining, expensive, attention-getting, and excessive material marks of success."

Twenty years after his first visit to Toisan in 1983, Lee "responded to an inner call to write" and began the 30 hours of interviews with his mother that eventually formed the foundation of this book. The duet of voices, mother's and son's, sets the reader gently into the boat of one family's history, then maneuvers it along a river wending between past and present, between an ancient, unchanged Toisan village and the cacophonous streets of contemporary Chinatown, USA.

The accounts of both worlds -- especially that offered by Lee's mother, Poy Jen -- are richly drawn and evocative, lending the book the dreamy wish-I-were-there appeal of a travel memoir. Poy Jen paints a picture of young green rice shoots waving in the Toisan breeze. In her narrative the reader can hear the creak of the rope as the water bucket is coaxed up from the stone well; smell the barbecued pork sizzling along San Francisco's Grant Street, and the shark's fin soup simmering in her Chinatown housing project kitchen. As she describes her efforts to keep such Toisan traditions as language, food and clan alive, her pride in her heritage is palpable.

"Suey Wan is the name of our village, and it is a thriving village to this day," Poy Jen explains in the first of her chapters. "Our soil was how sek -- rich and wet, for Toisan is in the Pearl River Delta. Water so shiny you have to squint to see it ... Life was not easy in the village like it is in America. Sweating and breathing hard. But still, we had lots more time to relax, to chat with one another, and to play. Once everything was done, it was done. You can't make the crops grow any faster by acting busy."

In one particularly poignant scene, Lee describes his first day of kindergarten -- his teacher the first Caucasian he'd ever met -- as "the day I crossed over." The "crossing-over" process accelerates as he enters high school. His teachers, along with some Chinatown elders, begin to warn him to keep his expectations low. Don't plan on becoming a CEO or a political leader, they say. Major in accounting. Start a small business.

"After her war-torn youth," Lee writes, "Mother was ever grateful for Chinatown's pacific if small cocoon. But for me, born and raised an American and indoctrinated to believe in the Declaration of Independence ... I was not so willing to be too readily deprived of my birthright. I wanted to know that America could work for me all the way, and if it couldn't, I wanted to do something about it."

Despite his teachers' admonitions, Lee did become a political leader of sorts. He was elected student body president at Galileo High School, joined a radical theater troupe, became a regular at City Lights Bookstore, and helped to organize the first Chinese-American civil rights march on Grant Avenue. "You were an intellectual at heart, with a strong sense of right and wrong, not a real troublemaker," Lee's mother says. "That's your character and I could stand with you."

But at 18, her son wanted to stand as far as possible from his family, even his beloved mother. "Like my parents," he writes, "I knew when it was time to leave the village." Lee was accepted to U.C. Berkeley and moved to a dorm on campus, 10 miles and a universe away from home. "My strongest memory of my first year of college is of clouds. Clouds of tear gas blanketing protesters ... clouds of marijuana smoke in our co-ed dormitory ... clouds of mental confusion as Marxists, conservatives, liberals, the Spartacist League ... and our outnumbered professors competed for our attention, our allegiance, our lives, and our souls." Loath to face his parents' disapproval about the amount of time and energy he was spending organizing campus protests and the diminishing attention he was allocating to his studies, Lee essentially cut himself off from his family -- until 1972, when his younger brother Richard was arrested for a Chinatown gang-related homicide.

Based on the testimony of a disreputable snitch and despite evidence that he was across town at a graduation ceremony when the shooting occurred, a jury purged of Chinese-American and African-American jurors convicted Richard of first-degree murder. Sitting in the courtroom beside his non-English-speaking mother, Lee realized as the verdict was being delivered that she didn't understand what was happening. "Richard lost," he told her in Chinese. His mother put her hands on the marble courtroom wall and began to wail.

"Maybe I was too busy raising baby John, trying to have some fun when I could," Poy Jen recalls. "Maybe I didn't watch over Richard enough. Maybe if I had, he wouldn't have gone to jail. I failed him as a mother."

"Mother had no soup that could balance the conflicting passions of justice and law, retribution and punishment, that were at play," Lee writes. Then in his third year at Berkeley, Lee threw himself into mounting appeal after appeal for his brother. He was on the verge of quitting school, but two caring professors talked him out of it. "Now there was no longer a rift between campus and Chinatown," Lee writes. The whole family would pile into the car to visit Richard in prison every visiting day, bringing care packages full of Chinese treats. Later, when Richard was allowed weekend-long family visits, his mother would cook chi soups and several-course Chinese meals in the prison trailer.

After years of fundraising, media campaigns and legal maneuvers, Richard's final appeal was denied. Lee boycotted his own law school graduation in protest, took a job as a lawyer at the Bank of America (where, he says, he was frequently insulted by his co-workers' racist comments), and fell into the suicidal depression he describes in the book's opening pages. After nearly killing himself in a motorcycle "accident," he quit his bank job, began studying Buddhism, and joined a theater troupe. In 2000, for his 50th birthday, he brought his mother back to Toisan for her first visit since she'd left her village more than 50 years earlier.

In the epilogue, Lee concludes, "I am finally at home in America and in Toisan." And his mother reports that she has fulfilled her eight promises. "I've taught [my children] to be nice to everyone, to help people they meet along the way, to not hold on to grudges or resentment at wrongdoing ... If I died and a supreme being granted me a choice to come back to this world or to stay in heaven, what would I decide? Oh, I'd come back -- no question about it. And oh yes, of course, I would ask to live in America!"

Lee raises pertinent questions that are left unanswered. We never learn what he's been doing for a living since he quit the Bank of America, nor why and how he became an architect, and then a lawyer. Near the end of the book Poy Jen refers to Lee's brother Richard as being "busy raising his two daughters" without explaining Richard's apparent release, at some point, from prison.

Despite these minor omissions, "The Eighth Promise" is a lively read and a significant contribution to the body of literature that continues to bubble up from the steaming cauldron that is the American immigrant experience.

Shares