"Breach" is based on the true story of FBI agent Robert Hanssen, who was convicted of treason in 2001 for having sold U.S. secrets to Moscow for some $1.4 million in cash and diamonds. Hanssen, an expert on Russian intelligence, was a 25-year veteran of the agency. When the authorities caught wind of his extracurricular activities, they gave him a new job, one that allowed him access to extremely sensitive information, and assigned a young and rather green surveillance specialist, Eric O'Neill, to be his assistant. They hoped, in a gambit that paid off, that O'Neill would help uncover the evidence they needed to catch and convict Hanssen.

That story sounds more like a movie than like real life, the sort of material that could lure even a smart filmmaker into the wilds of overdramatization and overkill. But the director of "Breach," Billy Ray, is too wily, too hip to the value of understatement, to make that mistake. Ray -- also the director of the 2003 "Shattered Glass," another movie about a creepy guy leading a double life -- likes to explore that murky gray area where self-delusion and the deception of others blend into a kind of egotistical religion of the self. When lies -- your own lies -- are all you can believe in, what use do you have for any sort of God?

Hanssen's story in particular is ripe for that kind of exploration: He was a devout Catholic, a member of the ultraconservative faction Opus Dei. He also made videotapes of himself and his wife having sex, which he'd share by mail with certain friends. In "Breach," Ray doesn't profess shock that a deeply religious guy could also be very kinky; nor does he take the blasé, jaded route of assuming that most deeply religious people are just pervs at heart anyway. With the help of the actor he's cast as Hanssen, Chris Cooper, Ray does something much more subtle and unnerving: He simply builds a case against Hanssen, layer by creepy layer, suggesting that this guy's religious zeal, his sex drive, his superior intelligence and his contempt for his country had somehow mingled into a bizarre and dangerous guiding philosophy. Cooper's interpretation of that is always fascinating to watch, and sometimes terrifying.

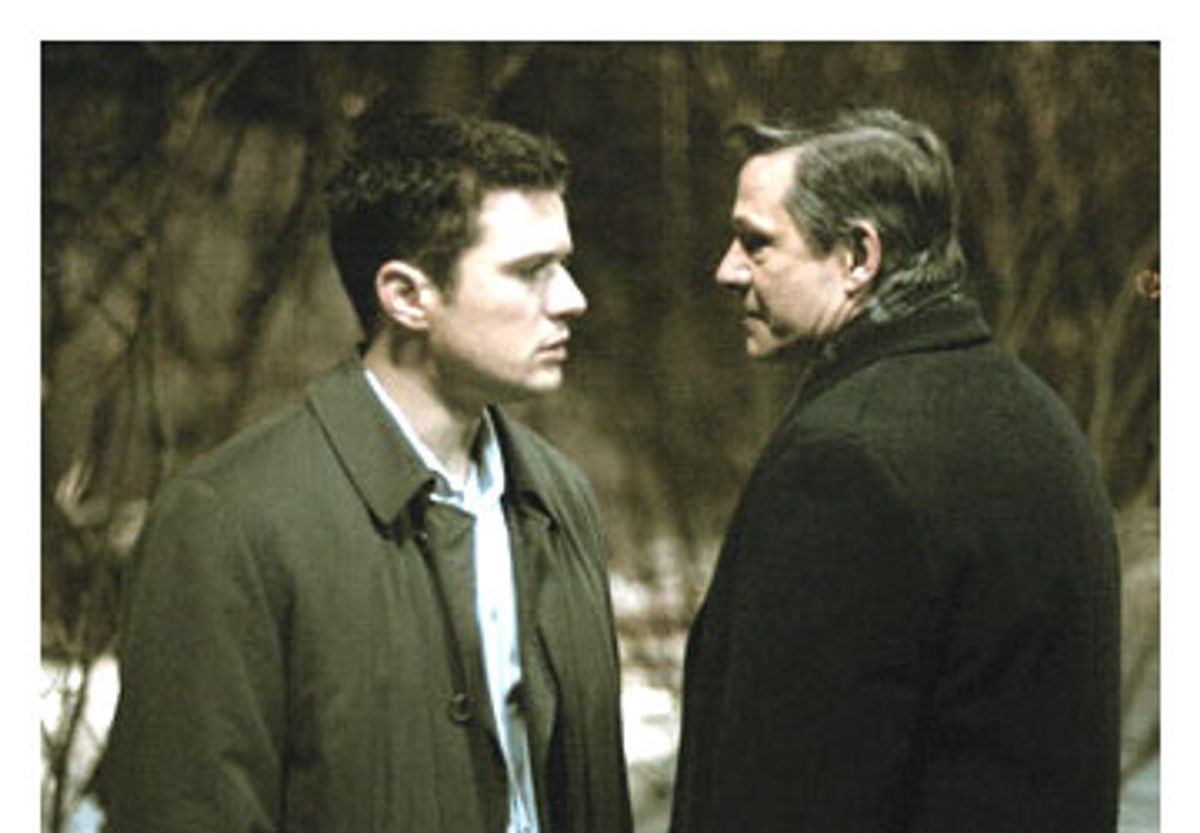

Ryan Phillippe plays young O'Neill, and he's got just the right look for an untested, aspiring FBI guy: His eyes, in their wide-open blueness, practically invite spilled secrets, but they're not yet capable of hiding hurt feelings. When he and Hanssen move into the new office they're going to share, the senior agent stares him down with his X-ray vision. Then O'Neill tries to get Hanssen to call him by his first name, and Hanssen shoots back, "Your name is clerk." The younger officer looks as if he'd been shot through the heart, but he rallies, as if Hanssen's arrogance had only bolstered his determination. I've often found Phillippe to be a bland, unreadable actor, but maybe he's finding ways to use his inscrutability as an acting tool. Particularly in some of the later scenes, where O'Neill realizes that betraying Hanssen's trust is going to cause him some pain as well, Phillippe finds ways to telegraph his feelings to us, even as he hides them from Hanssen. This may not be a dazzling performance, but it's at least an intelligent, carefully shaded one.

"Breach" is really Cooper's movie. Cooper is a marvelously expressive actor, and he's been wonderful even in terrible pictures, like Spike Jonze's egregiously self-congratulatory "Adaptation." As distinctive as his facial features are, he often looks like a different person from movie to movie: Here, he's a distrustful lizard with slippery-looking lips, and there are moments when it's hard to even look at him.

But Cooper also pulls off the near-impossible, making us feel dashes of sympathy for this twisted and unscrupulous man. In one scene, Hanssen is being groomed and fussed over by a photographer who's come to take his 25th-anniversary portrait. He tries to smile, an effort that nearly cracks his face in two. But his discomfort intensifies by the second as he sits stiffly in that chair: We can see him wishing he could jump not only out of that chair, but out of his own oily skin. He rushes out of the room before the session is finished, later, predictably, calling the photographer a "fag" and confessing that he just doesn't like to be scrutinized. Seeing Hanssen crack like that is gratifying, but it's also a little horrifying: We'd rather write him off as a monster than see him as a human being.

"Breach" -- the script is by Ray and the team of Adam Mazer and William Rotko -- is a nicely crafted picture, made with lots of intelligence and restraint. Sometimes that restraint makes it feel a little dull: In patches the movie is more sluggish than it needs to be. Still, it's far more vibrant, and far less self-important, than that other recent picture about powerful guys with big secrets, "The Good Shepherd." It even has its moments of grim levity: Laura Linney shows up as an FBI higher-up who's so devoted to her work that, as she puts it, she doesn't "even have a cat."

The picture is suspenseful where it counts, and at times, it's truly terrifying. There were moments that made my skin crawl: Hanssen and his wife, Bonnie (played with Stepford-like glassiness by Kathleen Quinlan), openly attempt to lure O'Neill -- who is Catholic, which is part of the reason he was chosen for the assignment -- and his wife, Juliana (Caroline Dhavernas), into making a deeper connection with the church. They show up uninvited at the young couple's apartment, bearing reheatable leftovers, and adopt an air of glazed friendliness as they chatter on about the importance of making babies, urging Juliana to eat lots of protein so she'll be able to conceive.

The scene is almost a mini homage to "Rosemary's Baby," and there are other moments in "Breach" that are unsettling in the same tacit, subterranean way. When Hanssen makes the "drop" that leads to his arrest, his actions are both unnervingly weird and shockingly mundane. In this pivotal moment, there are no drab overcoats, no mysterious code letters, no furtive phone calls: The tools of Hanssen's betrayal include some everyday items that you'd find in your kitchen or pantry. If you've got the wiles, and the desire, to bring down a country, the means are all too close at hand.

Shares