John McCain took to the Senate floor early this month while his colleagues were debating whether to debate a resolution condemning President Bush's plan to send nearly 21,500 more troops into Iraq. The senior Republican lawmaker has served as a proxy for Bush in the fight over the surge, and his argument on Feb. 6 fit the bill. McCain took on Majority Leader Harry Reid, who was leading the charge to pass the nonbinding resolution, with a simple message: If you believe the surge will fail, you are telling U.S. troops they will fail.

"I talked to many men and women in the military in recent days, ranking from private to general," McCain said, seeking to wrap his position in fidelity to the troops. "Isn't it true that most of them, if you had the opportunity to talk to them, would say: 'When they do not support my mission, they do not support me?'" McCain later said that the resolution might as well read: "I don't think you are going to succeed."

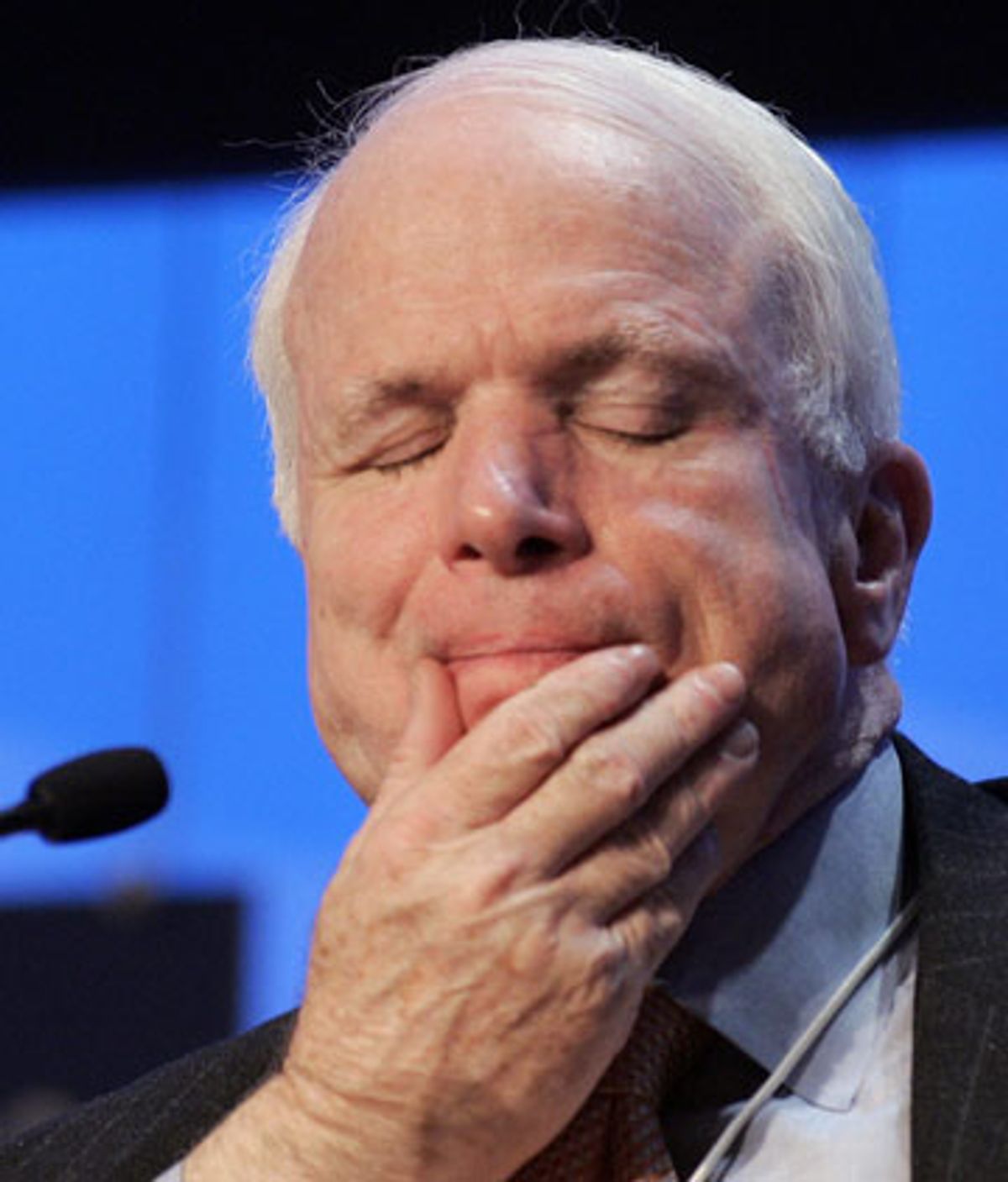

A war veteran and presidential contender for 2008, McCain seemed to be squarely in the president's corner during the Senate debate.

In fact, McCain has increasingly hedged his position on the surge, showing full support for Bush's plan one moment and then pivoting at another moment to point out grievous tactical errors he says are being made by the White House. For example, in front of a conservative audience at the American Enterprise Institute in January, McCain said that while the president was sending the minimum number of soldiers to Baghdad needed to make the plan work, the plan would indeed work. Then, on the Senate floor on Feb. 8, he announced that he was "very doubtful that we have enough troops" there to get the job done. Furthermore, while Bush agreed to an unconventional arrangement in which command for the surge will be split between U.S. and Iraqi military leaders, McCain warned the Senate Armed Services Committee on Jan. 23 that he knew of "no successful military operation where you have dual command." He has also suggested the Iraqis might not contribute adequately in the operation to secure Baghdad.

Political observers say McCain isn't just worried about military tactics. By simultaneously endorsing the surge and harshly criticizing certain aspects of the Bush plan as potentially disastrous, McCain appears to be hedging his bets should the surge fail. "He is looking for an exit strategy if it does not work," said Stephen Wayne, a political science professor at Georgetown University. "It says: 'You just did not do it right, Mr. President.'"

McCain's support for the escalation is consistent with his long-held belief that the United States has been short on troops in Iraq from the beginning. But some political observers have noted that it also buttresses McCain's recent, sometimes awkward efforts to cozy up to the GOP's conservative base before the upcoming Republican primaries.

It could be a risky gambit, pitting him against the broader general electorate, which, polls show, is opposed to the surge. "McCain is really in a tough position at the moment," noted Wayne. "If the surge fails and McCain is attached to it, it is going to be very difficult to run in the general election."

At times, McCain has come across as one of the Senate's harshest critics of the surge plan's tactics, stopping just short of predicting failure in Baghdad. He has certainly been far more critical of its tactical aspects than Bush's other main ally in the Senate, Connecticut's Joe Lieberman, who has stuck to unflagging endorsements of Bush's war policy.

Should Bush's plan fail, observers say, McCain is positioning himself as the man who would have had the right plan to win the war. "That is the way he is going to sell it," explained Michele Swers, a political science professor at Georgetown. "He would have done it right."

But this approach clouds McCain's argument that doubters of the surge don't support the troops. Other lawmakers -- including some Republicans -- have opposed the surge in part because they worry that the plan will fail. They say the best way to support the troops is to encourage the president to pursue other initiatives they believe are more likely to salvage the situation, including a renewed diplomatic effort in the region. "A surge was already tried in Baghdad last fall, and it failed," Jim Ramstad, R-Minn., stated on the House floor last Wednesday. "It's time for a surge in diplomacy, not a surge in troops, to mend a broken country."

In a brief interview just outside the Senate chamber last Tuesday, McCain sought to draw a distinction between his concerns about possible failure and the concerns of his colleagues who oppose the surge altogether. "They are saying that it will fail, because if you thought it would succeed, obviously, you would support it," McCain explained. "I think it can succeed. I believe it will," he said. "But I am by no means sure. As I've said, there are many uncertainties here."

That outlook contrasts with McCain's message when he and Lieberman established themselves as Bush's tag team on the surge during the January event at the American Enterprise Institute. Ensconced in a plush suite along with some of the White House's ideological kin, McCain argued there was a parallel between those opposed to the Baghdad plan and American isolationists prior to World War I. He also referenced the unconscionable failure to act early against fascism before World War II. He even added a bit of stump-speech flair: "I am of the firm belief that the United States and the West and our values and our principles are still transcendent," he said. "Our best days are still ahead of us."

McCain's seemingly temporary mind-meld with the neoconservatives at AEI is not the only example of his maneuvering to please a particular set of conservative Republicans. Another was his spring 2006 speech at Liberty University, which he gave with the Rev. Jerry Falwell at his side -- a man McCain had once denounced as an "agent of intolerance."

McCain has also zigzagged on campaign tactics, recently tapping the advertising firm behind the Swift Boat Veterans for Truth smear campaign against John Kerry, which McCain himself condemned in 2004. He has since hired other down-and-dirty GOP operatives whose work the McCain camp has frowned upon in the past. His fundraising strategy appears to be colliding with some of McCain's most high-minded ideals, such as his well-known disdain for the influence of private money on public policy. The Washington Post reported last week that McCain was enlisting the support of some big-time GOP pioneers of the very "soft money" tactics that McCain has denounced in the past.

This kind of maneuvering threatens to eviscerate what many view as McCain's most attractive and potent political asset: his image as the charismatic, maverick politician who set out on a "Straight Talk Express" bus tour seven years ago. "It strikes me that this is a guy who is really going back on himself," said Wayne, the Georgetown professor. "He would not accept soft money, but he is now going after the big donors. He is courting the Republican establishment as best as he can."

But his biggest gamble with any political hedging ahead of the '08 race may be with regard to Iraq. "In some ways there is some portion of primary voters who will respond to, 'Bush screwed up, but he screwed up by not sending enough troops,'" Swers said.

McCain remains careful when he lashes out about the war. While he sometimes mentions, almost as a footnote, that Bush is ultimately responsible for the failures in Iraq, he usually reserves most of his venom for Bush's lieutenants, most often arguing that the president has been poorly served by those subordinate to him. McCain had long been critical of former Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, a man Bush kept in that post for nearly six years. Late last month, McCain also blasted Vice President Dick Cheney, saying in an interview with the Politico that Bush was "very badly served" by the vice president.

Most recently, McCain led a pointed though unsuccessful assault on Bush's nomination of Gen. George Casey to become the next Army chief of staff. McCain's barrage focused on Casey's alleged shortcomings in his previous job as commander of U.S. forces in Iraq. When McCain went to the Senate floor on Feb. 8 to urge his Senate colleagues to reject Casey's nomination, he noted only in passing that Bush was ultimately responsible for what happens with the war. He quickly zeroed in on Casey, saying "presidents also rely on the advice and counsel of their military leaders."

Swers says that McCain's tough talk about the president's deputies isn't by mistake. "That is the political part," she said. "He does not want to denigrate the power of the presidency. So you denigrate the advisors," she said. "It helps him," she added, by putting him in a position "to benefit from the Bush machine and its connections."

The best way to deal with concerns about Bush's surge plan is not to oppose it, McCain says, but to more carefully monitor the situation in Iraq. McCain has introduced a competing resolution in the Senate with a raft of benchmarks for the Iraqis to meet. The benchmarks, if met, are designed to help the military effort in Baghdad succeed. Carefully monitoring the 11 benchmarks -- ranging from easing de-Baathification efforts to building an independent judiciary -- will help lawmakers better decide if and when to pull the plug on Iraq, McCain contends. "That is why we put benchmarks in our resolution," McCain said during the interview last week. "At least we have some measurement of how those benchmarks are met."

And if there is little progress -- and ultimately failure -- in Iraq, McCain will at least be in the position of having predicted it.

Shares