After George H.W. Bush won the 1988 presidential election, there was, as usual, ill-informed speculation that Donald Rumsfeld would be offered a senior cabinet post. One of those who paid attention to the rumors was Milt Pitts, the longtime presidential barber, who was summoned to give the president-elect a trim soon after the victory. "Pitts had always liked Rumsfeld," a former White House official explained in recounting the ensuing conversation.

"I've heard that Don Rumsfeld might be secretary of defense," said Pitts brightly as he snipped away. "Have you heard that, Mr. Vice President?"

"No, Milt," said Bush in a low, chilly voice. "I haven't heard that."

Rumsfeld himself was ready to settle for something less. Writing to congratulate Bush on his victory, he stated that he would "like to be your Ambassador to Japan." An official in the Bush transition office processing such requests found that the letter had already been reviewed at a high level. Scrawled across it were the words "NO! THIS WILL NEVER HAPPEN!! GB."

Rumsfeld was offered no position in the administration of George H.W. Bush.

A few months after the inauguration, Donald Rumsfeld was invited to play the role of president of the United States in an exercise devised by a Washington think tank. In this scenario, "President" Rumsfeld was intent on securing congressional approval to go to war. "I don't care what you tell them," he barked at White House chief of staff Ed Markey, "just get over to Capitol Hill and make them do it, and make sure there are no constraints."

"It was an exercise devised by the Center for Strategic and International Studies [CSIS] to study the functioning of the War Powers Act," remembers Markey, a liberal Democratic congressman from Massachusetts. "We acted out roles. I accepted the role of Chief of Staff because I figured that was my only shot at the job." Rumsfeld may have felt the same way. At the age of fifty-seven he appears to have concluded that if he could no longer realistically aspire to be president, he could at least act the part.

By all accounts "President" Rumsfeld played his role in that 1989 exercise for CSIS with great gusto, raging at the obdurate Congress and deploying the "White House spokesman" (played by the venerable broadcast journalist Daniel Schorr) to maneuver the press into supporting his martial position. But this Washington exercise was a comparatively lighthearted affair compared to Rumsfeld's role in games that were far more elaborate, and deeply secret. Well away from journalists and others lacking highly restricted security clearances, he could perform not merely as a chief executive, but one faced with the awesome responsibility of waging nuclear war.

The games were designed to test a program known as COG, Continuity of Government, and they concerned the ability of the government to continue to function during and after a nuclear attack. Everything about these exercises was secret. "There are seven levels of classification used in the government," one former senior Pentagon official told me when I raised the subject. "You are asking about the most secret level of all." Plans to enable the government to survive a nuclear attack dated back to the early days of the cold war, when vast bunkers were excavated in the countryside around Washington in which the various organs of government could take shelter. At least one of these, in the rural Virginia town of Culpeper, was even supplied with Barbie dolls for the diversion of officials' children sitting out the war underground. Over the years these efforts became ever more elaborate, and of course vastly more expensive. A major development occurred in the early 1980s, when Ronald Reagan was sold not only on the notion of a missile defense shield, but also on the practicality of fighting a prolonged strategic nuclear war, lasting up to six months. This decision lent added emphasis to the need for keeping the machinery of government going amid the radioactive ruins.

In consequence, the money allocated for COG began to soar to previously undreamed-of heights. A prime architect of the revised system has disclosed to me that the budget hit $1 billion a year by the end of Reagan's first term. Lending intellectual weight to this costly initiative was Andrew Marshall, an influential defense intellectual who had first crossed paths with Rumsfeld when he was secretary of defense. Early in the Reagan years, Marshall predicted that a "weakening" Soviet Union might lash out in a surprise nuclear attack, thus necessitating the extensive facilities in which Rumsfeld was invited to exercise his post-apocalypse leadership skills.

Marshall and others had long maintained that the Soviet strategy involved "decapitation" of the US leadership and that therefore some of the first warheads would land on Washington, very possibly obliterating the president and other senior officials. COG planners therefore began training teams of individuals experienced in national security matters who would be ready to take over and resurrect some sort of government. The teams were divided up by function, one for the Defense Department, one for the State Department, a third for the White House and so on.

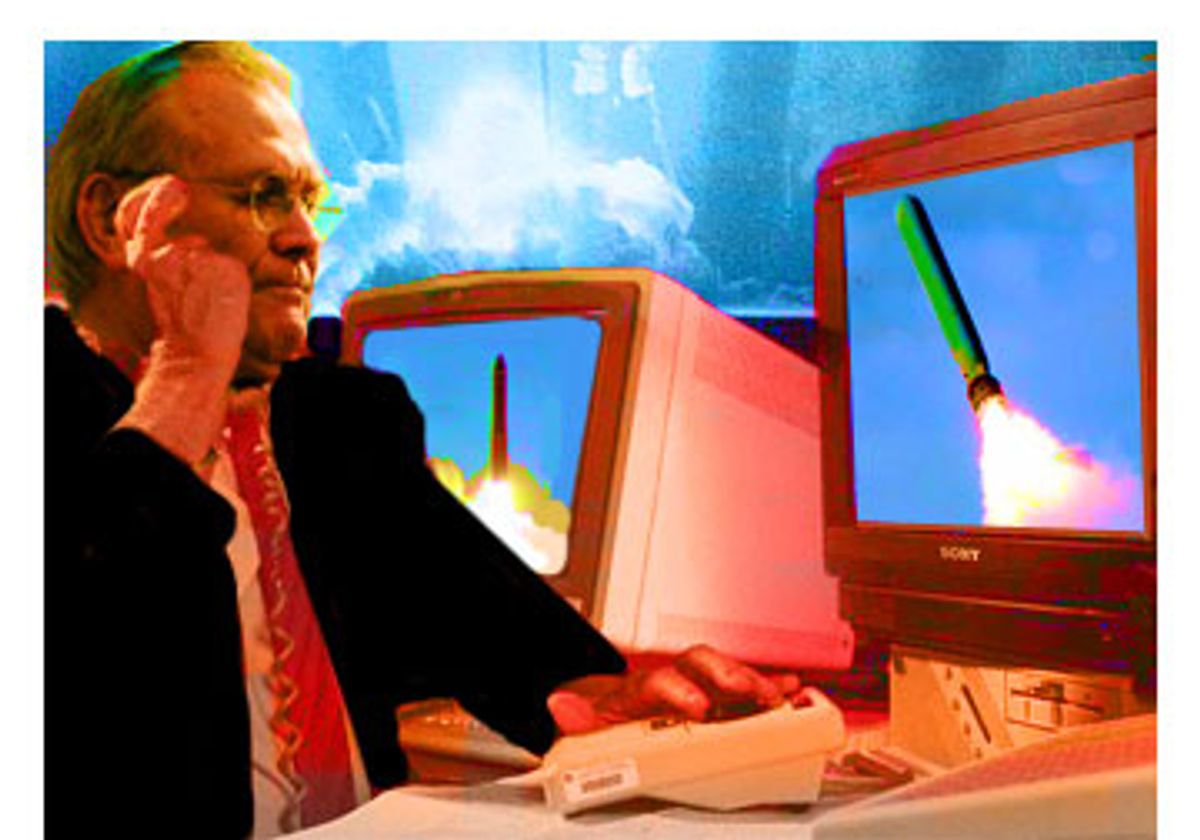

This highly secret program was known as Project 908, and among the individuals earmarked to take power when disaster struck was Donald Rumsfeld. Every so often he would disappear from his Chicago office, leaving no word of where he was headed, or why. Once off the map, he would be moved on a military transport to one of the secret headquarters created as part of the COG network. There, for several days, he would be immured in artificial caverns, staring at electronic displays streaming data of disaster and confusion, sleeping on cots and subsisting on the most austere rations. As often as not, players who had been brought to the locations on planes with blacked-out windows had no idea where they were. A participant in one exercise recalled that "we knew we were in the South, because the people serving the food had Southern accents, but that was all."

Rumsfeld loved these games. There were others who were frequent players in the exercises, notably Dick Cheney. "Cheney and the others often had other priorities," recalls the former Pentagon official. "Rumsfeld always came." He wasn't just trying to organize a devastated country. He was fighting World War III, or at least simulating what nuclear theory suggested such a conflict would be like.

Herein lies an aspect of Rumsfeld's career -- and character -- that remained deeply buried even after word of his participation in the COG exercises leaked out. Faced with the most awesome choices a simulated environment could present, placed in a situation that was designed and advertised as a rehearsal for what might one day be terrifyingly real, Rumsfeld had one primary response. He always tried to unleash the maximum amount of nuclear firepower possible.

The teams taking part in the game were presented with two main tasks: reconstitution of some sort of working government, and retaliation against whomever had inflicted the disaster. The first of these, reconstruction, was generally considered the most urgent. But this part, according to fellow players, did not interest Rumsfeld. "He always wanted to move on to retaliation as quickly as possible," recalls a former senior official in the office of the secretary of defense, "he was one who always went for the extreme option."

A former participant, enlisted to take the role of a senior national security official, described how his "war" began with a limited Soviet attack in Europe. "It seemed quite possible to defuse the crisis," he recalled, stressing that the State Department "team," was working to avoid an all-out thermonuclear exchange. Rumsfeld, however, had a different agenda. From the outset, this participant remembers, the once and future defense secretary was determined to "launch everything we had left" at the entire communist bloc, Russians and Chinese together.

The individual playing the part of secretary of state, however, a canny retired diplomat, was no less determined to stop Rumsfeld obliterating several million people. Using every tactic and stratagem he had learned over the course of a long career, the diplomat waged bureaucratic warfare over the postnuclear communications system linking the secret hideouts. As an added note of realism, the State Department official playing the role of deputy to the "secretary" evidently thought that his real-life career would be enhanced by supporting Rumsfeld, and therefore did his best surreptitiously to undermine his notional superior. Even so, the diplomat ultimately prevailed. The northern hemisphere survived. Rumsfeld, deeply chagrined at having lost the argument, never forgave his antagonist.

Of course, immured in the COG bunkers, Rumsfeld and his fellow players were not enacting anything based on real experience (apart from familiar routines of bureaucratic backstabbing). Nuclear conflict existed only as a game. In fact the theorists who worked on nuclear strategy were fond of quoting what they called game theory. No one had the slightest idea of what might actually happen in a nuclear war. Even the known "facts" were anything but. Plans based on tidy predictions of the explosive power or "yield" of various weapons, for example, were belied by tests in which the results often varied wildly from forecasts, as did the accuracy and reliability of intercontinental missiles, which were never tested in operational conditions. Such awkward realities never featured in nuclear war planning, let alone the scenarios concocted by the nuclear theoreticians for the games.

Hopefully, we will never know how any politician, let alone Rumsfeld, would act when presented with the option of launching nuclear weapons in real life. Unfortunately, we do know how Rumsfeld reacted to the option of attacking a country with conventional forces and overthrowing its government. We shall be examining the invasion and occupation of Iraq in later chapters, but it is worth comparing Rumsfeld's behavior in the COG games with his performance in a real war. As we shall see, the casual, maybe even irresponsible decisions taken in that war reflect attitudes and reactions better suited to an elaborate game, from which real-life costs and consequences are excluded.

Insofar as the COG games gave the illusion of reality, they taught Rumsfeld and his fellow players some dangerous lessons, particularly when the fall of the Soviet Union induced some changes in the usual scenarios. Although the exercises continued, still budgeted at over $200 million a year in the Clinton era, the vanished Soviets were now customarily replaced by terrorists. The terrorism envisaged, however, was almost always state-sponsored. Terrorists were never autonomous, but invariably acted on behalf of a government. "That was the conventional wisdom," recalled retired air force colonel Sam Gardner, who has designed dozens of war games for the Pentagon and related entities. "Behind the terrorist, there was always something bigger, and the games reflected that."

There were other changes too. In earlier times the specialists selected to run the "shadow government" had been drawn from across the political spectrum, Democrats and Republicans alike. But now, down in the bunkers, Rumsfeld found himself in politically congenial company, the players' roster being filled almost exclusively with Republican hawks.

"It was one way for these people to stay in touch. They'd meet, do the exercise but also sit around and castigate the Clinton administration in the most extreme way," a former Pentagon official with direct knowledge of the phenomenon told me. "You could say this was a secret government-in-waiting. The Clinton administration was extraordinarily inattentive, [they had] no idea what was going on."

Excerpted from "Rumsfeld" by Andrew Cockburn. Copyright © 2007 by Andrew Cockburn. Reprinted by permission from Scribner, an imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Shares