A recent, characteristically beard-stroking New York Times article pondered the way reporters at an international press junket for the computer-generated extravaganza "300" -- an adaptation of comics guru Frank Miller's 1998 graphic novel about the 480 B.C. battle of Thermopylae -- zealously attempted to read the movie as a metaphor for George W. Bush's war on Iraq. Is the movie's Persian potentate Xerxes, a megalomaniac who considers himself both a god and a king, supposed to embody W.'s hubris? Or is Leonidas, the Spartan ruler who led 300 valiant Greek soldiers against a zillion-man Persian army, the real presidential stand-in?

In the movie, a Greek naysayer tells Leonidas, "I know your kind too well. You send men to their slaughter for your own gain," and I could hear critics across the land, trawling for scraps of political topicality, scribbling madly in their notebooks. But you'd have to be Reed Richards to find firm contemporary parallels in "300" -- no mere mortal should stretch that far. The movie's terms are unapologetically comic book, with all the good and bad that implies: You've got a bunch of noble warriors outnumbered by bullies. It's not hard to know which side we should be rooting for.

The bigger question to ask about "300" is why, for a supposedly rousing tale of heroism, it's so curiously unaffecting. Directed by Zack Snyder ("Dawn of the Dead"), the picture, like the earlier Frank Miller adaptation "Sin City," is a blatantly unreal-looking blend of computer graphics and live action. But even within the context of its aggressively artificial visuals, "Sin City" -- which was directed by Robert Rodriguez -- still acknowledged its debt to classic film noir cinematography. Its shadowy textures and chiaroscuro contrasts may have been coaxed to life on a computer screen, but in their own way, they honored classic filmmaking conventions, even as they evoked the stark woodcut quality of Miller's artwork.

"300" is a movie set in the past -- about 2,500 years in the past, to be exact -- but it feels like a purely modern creation. Like "Sin City," "300" combines live action with digitally created backgrounds. But the picture is, weirdly, both vivid and flat: Its color tones, ranging from cool green-grays in some scenes to sepia splashed with black-red in others, are so carefully calibrated that they come off as sterile. The picture faithfully mimics the mood, color and compositions of its source material. (The book "300" was written by Miller and Lynn Varley. Miller is also one of the movie's executive producers.) But it lacks the rugged vitality, and the dynamism, of Miller's drawings. Miller's "300" pictures leap off the page; on the movie screen, they roll over and play dead.

The actors (including Gerard Butler, of "Phantom of the Opera" fame, who plays Leonidas with grave stiffness) march around in package-enhancing skimpy outfits, and their skin glows. But the film has a poreless, waxen quality, as if all sensuality had been airbrushed out of it: The actors struggle valiantly to take hold of their characters, but deep down they know they've donated their bodies, and their faces, to science.

In places, "300" -- which was written by Snyder, Kurt Johnstad and Michael B. Gordon -- is so audacious that it scales the heights of high camp. The movie opens with a back story, as one-eyed warrior Dilios (David Wenham) spins the tale of how King Leonidas grew up to be such a brave warrior and leader: Deformed or otherwise inferior Spartan babies are killed at birth; but the sturdiest young males are trained in combat from an early age, and Leonidas excelled at twisting the limbs and cracking the heads of his little opponents. The grown-up Leonidas has earned the respect of his kingdom and the love of his take-no-prisoners Spartan spitfire wife, Gorgo (Lena Headey). But one day a Persian messenger shows up, stirring up trouble. After consulting an oracle -- a seminaked redhead in a filmy gown -- Leonidas realizes Sparta must defend itself against the Persian threat. He assembles an army of 300 fearless, highly disciplined volunteers and heads out to drive back the enormous Persian army, although his bold decisiveness is challenged by Spartan statesmen Theron (Dominic West), who'd prefer to negotiate for power than fight for it.

"300" marches forward with an almost insane degree of authoritativeness. Spartan he-men spout declarative sentences like "Only Spartan women give birth to real men!" and sneer at their fellow city-staters, the Athenians, calling them -- with straight faces -- "boy lovers." Then they don battle garb consisting of leather Speedos and flowing deep-red capes; when the fighting starts, they add helmets and strap-on shinguards, but their pectorals, and the rippling contours of their washboard stomachs, remain exposed, Village People style. In one scene, Leonidas watches as a young soldier demonstrates his spear-chucking prowess: "Fine thrust!" he says, nodding approvingly. It's an obvious nugget of comic-book homoeroticism, but Snyder doesn't let himself, or his actors, have fun with it: The movie stays well inside its closet of self-seriousness.

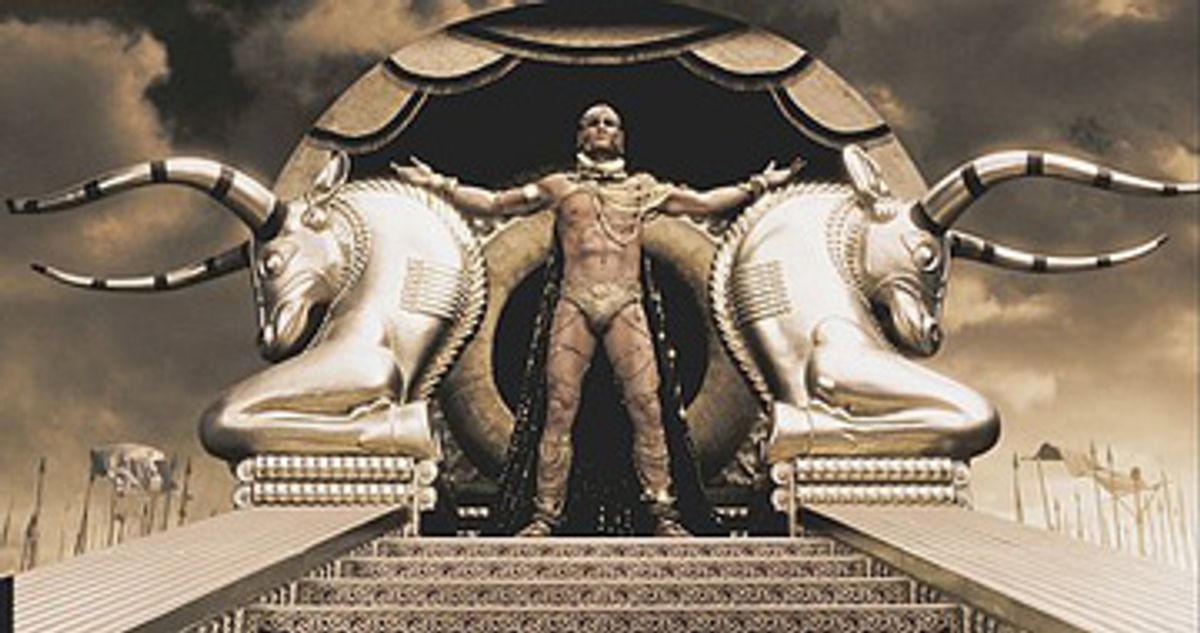

The battle footage here features lots of guys jabbing one another straight through with spears, as well as one zinger of a decapitation. All of this is accompanied by spurts and sploodges of highly art-directed black-red blood. The violence in "300" is stylized almost to the point of tastefulness, but don't worry: There's plenty of tackiness to go around, and I'm still not sure how much of it is intentional. Xerxes (played by Brazilian actor Rodrigo Santoro), dressed in a shimmery frock of chains and jewels, makes his appearance on an art-deco parade float, borne on the shoulders of Persian slaves. There's a throne at the top and a movie-palace staircase leading down: His silver eye shadow glistening in the movie's highly artificial light, he shimmies down those steps like a pre-code Gloria Swanson -- something tells you Gorgo isn't the only queen in town.

But in this most manly Spartan universe, Xerxes must also be a symbol of homoerotic evil, a fact that becomes dazzlingly clear when a Spartan hunchback named Ephialtes (Andrew Tiernan) drops into his lair. Ephialtes has begged Leonidas to let him fight; Leonidas, citing Ephialtes' physical weakness, declines, suggesting, instead, that he could carry food and water to the soldiers. Wanting none of that sissy stuff, Ephialtes stomps off, and is lured to the dark side by Xerxes, whose palace is a den of hot lesbo action and amputee go-go dancers.

Scoping out the scene around him, Ephialtes can't believe his bulging eyes. Xerxes tells him that if he'll swear allegiance to Persia, the most sensual pleasures imaginable will be his; to prove it, a few of Xerxes' comely slaves rub their bejeweled nipples against Ephialtes' barnacled hump -- an admirable bit of ingenuity on their part, considering some of them don't even have arms.

The scene is one of the rare moments in "300" when Snyder lets himself go straight over the top, acknowledging that really, after all, this stuff is supposed to be fun. But it's too little too late. Some of my colleagues have expressed the fear, not wholly unwarranted, that movies like "300" -- pictures made largely on computers -- are the wave of the future and will eventually supplant conventional filmmaking. I don't think that's going to happen anytime soon: "300" may make money, but I doubt even the least discriminating yobbos on the planet would want every movie to look like this. We go to the movies to see people who look like us -- they may be better-looking versions of us, but their humanity is still the selling point. "300," even with its impressive vistas of computer-generated soldiers, is just a throwaway epic. As Xerxes' unacknowledged patron saint Swanson once said, "We had faces then." Until further notice, we still do.

Shares