Once we reached Mason City, the reporters on the bus began loading baby pictures onto their laptop and cellphone screens. John and Cindy McCain just could not get enough of the cute kids. "Awww," cooed Cindy, as a digital photograph of a 7-year-old in a blue blazer was handed around. "A beautiful smile," said John. "Take lots of pictures. We took thousands, but we wish we'd taken tens of thousands."

The bus had stopped at a railroad crossing, almost exactly 11 hours into the relaunch of the Straight Talk Express. The final town hall of the day had just ended -- the chili dishes emptied, the bumper stickers distributed, the applause lines well received. Everyone was too tired to keep asking hard questions. So talk turned to John's love of boxing matches in Vegas, and the final days of Bob Dole's hopeless 1996 presidential campaign, when the McCains crisscrossed the country for the loyalty and the kicks. "He was unleashed," John remembered fondly of Dole. "He knew he was going to lose."

By all appearances, the national press had somehow become one with the McCain campaign. We had been with him all day, nearly a dozen scribblers from the major papers, news Web sites, networks and wire services. We reclined on the motor coach's two couches, set our papers on its tables and swiveled in its leather chairs. There were six flat-screen televisions to watch the NCAA basketball finals, free WiFi for filing stories, packs of playing cards and boxes of powdered Donettes. A framed fern print hung above the toilet. We all sank into our seats, guests of honor mingling with senior staff, munching potato chips and Butterfingers with the candidate, peppering him with questions, and waiting for him to stumble. It went on for hours, with the subjects breaking in waves: Iraq, his age, military contracting, Jack Abramoff, the Bush administration, immigration, gays in the military. Everything was on the record, and nothing was off limits. It was a reporter's dream. David Broder, the grand muck-a-muck of campaign columnists, once called the national political press "the Screening Committee." John McCain, on the other hand, calls it "my base."

McCain was playing a game he had mastered once before, with the original Straight Talk Express. Back in 2000 he had stunned the American people, and seduced its political press, by offering endless on-the-record access, as if he had nothing to hide. The resulting buzz had helped make him, for a time, a real threat to the party's chosen candidate, George W. Bush.

It was a strategy no one has attempted since. The risks are too high. The political press can build up a candidate, for sure. But it loves nothing more than to destroy. As we sat through the hours of conversation, the scribblers all waited for the same thing. We only needed one flub, one unexpected admission, one apparent tear like Edmund Muskie's in New Hampshire, one "brainwashed" comment like George Romney's about Vietnam, one "Dean scream." This is why presidential contenders hide behind a phalanx of hired preppies, spokespeople and surrogates. It is why most reporters would have to sacrifice their firstborn before front-runners Hillary Clinton or Rudy Giuliani offered them unfettered on-the-record access.

McCain dodged and weaved plenty in his answers, but he always remained engaged, as if he were daring us to bring more heat, more traps, more opportunities for a mistake. If a question took too long to ask, he faked a snooze or impatiently tossed a water bottle between his hands. "What else?" he prodded. The New York Times' Adam Nagourney struggled in his swivel chair on a story for the next day's paper, so McCain's taunted him, calling him "you old geezer." Later McCain loudly teased John Weaver, his political mastermind, for losing the primary election in 2000 to President Bush. When McCain's Motorola Razr cellphone rang -- South Carolina's Lindsey Graham with an update on a Senate vote -- he did not excuse himself. "Hey, Lindsey," he called out. "What happened?"

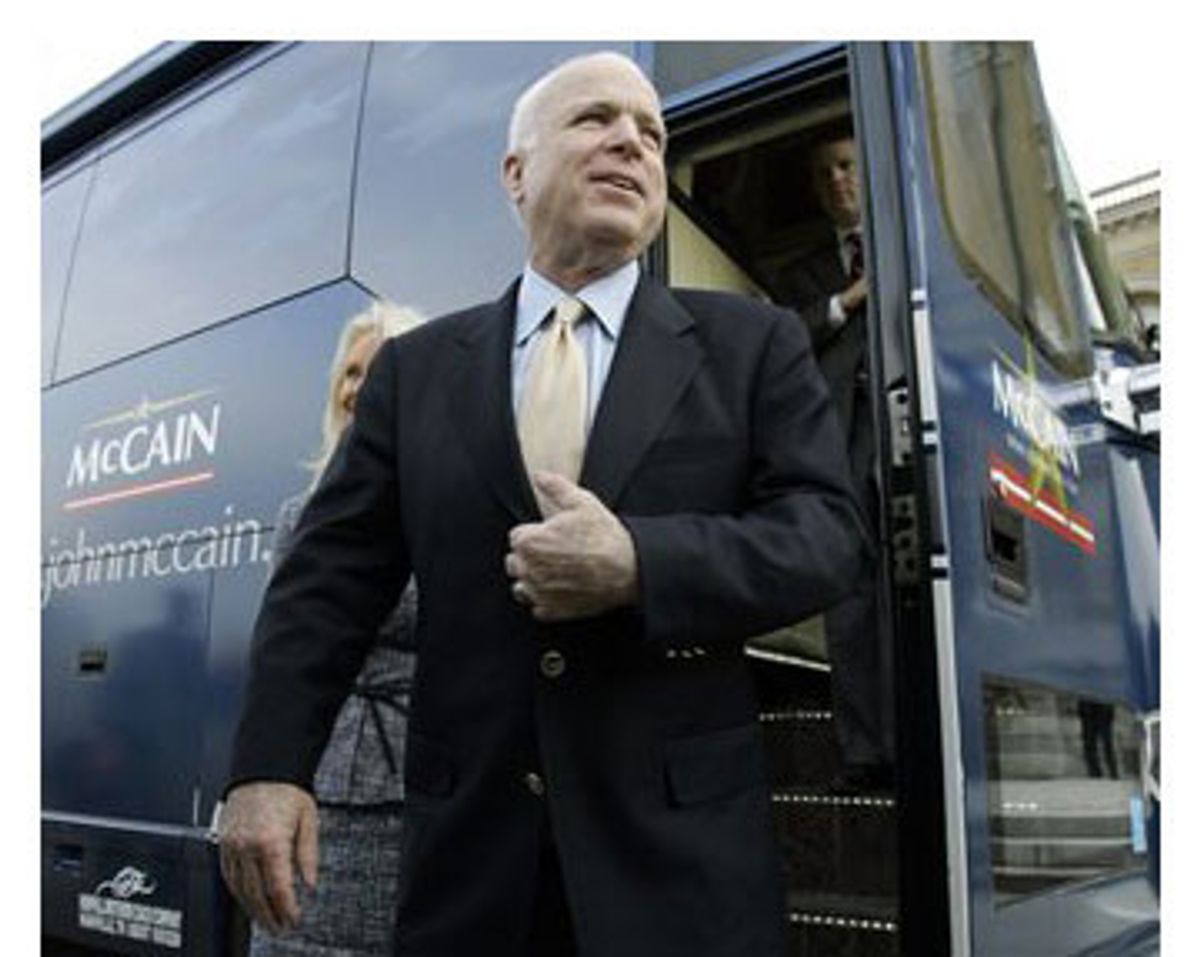

The day had begun at 8:30 a.m. in the driveway of a Des Moines Marriott. For an hour, the Straight Talk Express drove in circles around the city, in a ridiculous self-parody, so the networks could shoot their interviews with the illusion of a bus that was going somewhere. Finally, the motor coach parked itself in front of the Iowa state capitol, a five-minute drive from the Marriott, so the still photographers could get their shots in front of the city's skyline. McCain came out and held a press conference, looking tense and annoyed, while Cindy shivered beside him. "Little bit older, but still the same candidate," McCain announced, hitting the day's talking point. "Still having fun. Still on the bus. Having the town hall meetings in the same way we were before." What he didn't say was that none of this had really happened yet. He certainly didn't look like he was having fun.

As the morning wore on, it appeared that McCain's return to the trail might be a dud. The Straight Talk Express seemed to have been replaced, as the late Jean Baudrillard would have put it, by the spectacle of the Straight Talk Express, a pale media simulation of the original, devoid of meaning and filled with empty photo ops. The story seemed easy to write: The old McCain, who once called Pat Robertson and Jerry Falwell "agents of intolerance," had been replaced by a new McCain who spoke at Falwell's events -- a new McCain who would, in short, do anything to get to the White House.

But after a rocky first event in Ames, that story line faded away. His morning press conference seemed less of a farce and more of a prediction. At the town halls in Mason City and Cedar Falls, he loosened up and delivered enthusiastic stump speeches to rooms that, despite Rudy Giuliani's widening lead in early polls, were packed with hundreds of receptive party activists. There were a few catcalls about McCain's stance on immigration, but the mostly elderly crowd applauded his pledges to cut back spending and govern in the spirit of Ronald Reagan.

When he climbed back on the bus, McCain really began to hit his stride, powered by a considerable appetite for Fritos and chocolate candies. "Anything you want to talk about," he offered to his interrogators. "One of the fundamental principles of the bus is that there is no such thing as a dumb question," he added later. So, of course, the scribblers launched into a series of questions that most presidential candidates would frown upon, and he ducked and weaved with a sort of glee. Had he ever dressed in drag? "No ... At the Naval Academy, it was frowned on." What about the morality of homosexuality? "I just don't think it's the purview of public policy." And what if one of your children was gay? "That really is a family matter." What about the vice president's lesbian daughter having a child? "No opinion."

On a dozen other issues, however, he did weigh in, providing insights seldom offered by other candidates. What about his temper? "I was mad in South Carolina," he said of his 2000 campaign, when Bush unleashed a torrent of negative attacks. "It hurt me and it showed. People don't like angry candidates." So how could he now stand on a stage with Bush or leaders of the Christian right who had campaigned against him? "My life has been one of reconciliation. Reverend Falwell came to my office and said, 'I want to put our differences behind us.'" What did he think of Sen. Ted Kennedy, a boogeyman for many in his party? "Frankly I've enjoyed working with him because his word is good." Has Bush failed to address global warming? "I just think it's a failure of the entire administration." Would he sign Grover Norquist's no-new-taxes pledge? "I don't think I am required to sign any pledge of Mr. Norquist's."

Then came what seemed, at first, like a softball question. What has Bush done right? "Tax cuts. The effort to make tax cuts permanent." He faltered. "I know there are many others. I'm just drawing a blank." A moment later he recovered, listing off HIV drug funding in Africa, No Child Left Behind and something about national parks. As for his praise for Bush's tax cuts, he didn't immediately acknowledge the irony. He voted against them in 2001, but now says they must be continued because he opposes tax increases. What about the war in Iraq? "The mishandling of this war staggers the imagination."

The last time McCain ran for president he started with a van in New Hampshire, not a rock star's bus in Iowa. McCain was a long shot in 2000, with no real money and a jury-rigged campaign. Now he is a front-runner, with an organization that more resembles Wal-Mart in its size and scope. He is also seven years older, entering his eighth decade, and the times have changed around him. His conservative voting record remains unchanged, with constant support for pro-life positions. At the same time, he remains a self-marketed maverick in Congress, butting heads with the White House on campaign finance reform, global warming, pork barrel spending and a bill that bans torture. He voted in favor of stem-cell research and against a constitutional amendment to ban gay marriage, saying the issue should be left to the states. But on the issue that matters most, the Iraq war, he is on the wrong side of the popular polls.

Back in 2000, when he was riding high, he used to tell town hall audiences, "I will never be driven by a poll in conduct of American security policy. I promise you that." Now that statement has been put to a test. He has become the most vocal national supporter of the so-called surge in Iraq. As the campaign continues, the war's critics will blame him, as much as Bush, for every new body bag that comes home, for every news cycle that suggests again that the war is lost. McCain knows it. Weaver knows it. "We pray like all Americans that the Petraeus strategy works. But if it doesn't, there will be a political price to pay," said Weaver, the campaign's top strategist, referring to the general now in charge of Iraq. "I don't worry about it. There's nothing I can do."

On the trail, McCain claims repeatedly that the Iraq war can be won. To hear him tell it, his support of the surge is a matter of integrity, unconnected to the fact that polls show that around 70 percent of Republicans primary voters still feel invading Iraq was the right decision. It is a campaign theme he will no doubt take into the general election, if he wins the nomination, telling every crowd he meets that he is willing to lose the White House if it means winning the war. "The irony of ironies," he said on the bus. "I was the biggest complainer about how it was being conducted at the time. But life is not fair." When he spoke to the packed crowds in Ames, Mason City and Cedar Falls, Iraq was the first issue he brought up. "We have to begin our conversation with the war in Iraq," he said, a line that other Republican candidates are not likely to copy. "I am convinced that if we lose this conflict and leave, they will follow us home."

From a distance, it sounded like he was aping White House talking points. But the comparison only went so far. "Couldn't we go back to a level of civility where we don't question each other's patriotism all the time?" he told one crowd, eliciting rousing applause. He repeatedly recommended two books on Bush's foreign policy disaster, "Cobra II" by the New York Times' Michael Gordon and "Fiasco" by the Washington Post's Thomas Ricks. "I don't think the Madrid bombing had anything to do with the war in Iraq," he said on the bus, a line unlikely to escape the lips of Bush. Then he delivered another. "I am not sure at the moment we are succeeding in the war on terror."

But such nuance is lost in most political campaign coverage. The newspaper scribblers only have space in their stories for about two paragraphs to describe McCain's positions. The television networks have almost no time at all. The rest of the space is devoted to framing the event and describing the horse race -- the concerns of conservatives, the concerns about his age, the concerns about his closeness to Bush and the war strategy, the question of how much this Straight Talk shtick is just an act. The top of the story is reserved for McCain's mistakes, which are inevitable given the format. During one of his town hall addresses, which can be as freewheeling as those on the bus, he said that Republicans "lost the war," when he meant to say Republicans "lost the election" in 2006. He corrected himself. At another address, he used the word "tar baby" in its proper context, without any apparent racial overtones. But minutes after the speech, he said he regretted using the word, which has long been taboo in politics.

His biggest flub came in response to my question about taxpayer-funded contraception in Africa to prevent AIDS. At first, he said he would support it, along with abstinence education. Then he got confused, worried that he had dug himself a hole. He said he wasn't familiar with the issue and didn't know his own position. He asked Brian Jones, his communications director, for help. "You've stumped me," McCain said, before clamming up as the scribblers ganged up on him, asking more questions about the efficacy of condoms and sex education. Within hours, the Washington Post, the New York Times and Salon's War Room all had blog posts up about the incident, suggesting it was a window into the essential McCain dilemma: Can he appeal to social conservatives while struggling to remain authentic? It became the headline of the day. In response, a blogger at the New Republic declared a bit triumphantly: "There is no way that he can hold up under a year's worth of questions like this."

The reality could be far more unpredictable. McCain and Weaver have promised to run the campaign throughout with an open-door policy, despite the obvious risks. On the bus, McCain joked that the press would never forgive him if he did otherwise. "I'd have to hire a food taster, someone to start my car in the morning," he said. There is no doubt that he is determined to win over the media again, by offering us the ego-inflating pleasure of riding the country as a peer to a possible president of the United States.

But candidate McCain has also re-embraced a radical notion for this modern era of e-mailed opposition research and minute-by-minute news cycles, when a sound bite can be heard instantly around the world but a position paper is never read. He is betting that voters will forgive a front-runner's public flubs, and the headlines they produce, if they feel they are voting for a real person, not a consultant-managed product. He is, in other words, deeply wedded to the idea of being "unleashed," like Bob Dole in the final days of the 1996 election, once he abandoned hope and decided to ignore the consultants around him. "I'd rather make the mistakes and go on," McCain said. "Life's too short." Besides, he added, he liked the challenge. "It invigorates me. It keeps me on my toes."

It is still too early to know if Weaver and McCain will keep their word as this long and brutal campaign enters its final months. But the other presidential candidates would do well to take notice. McCain is again laying out a challenge to the presidential field: Come out from behind the pre-programmed events and five-minute "press availabilities." There may be many reasons why he should not be the next president of the United States, but McCain's willingness to be quizzed for hours by reporters trying to unearth new information is certainly not one of them.

Shares