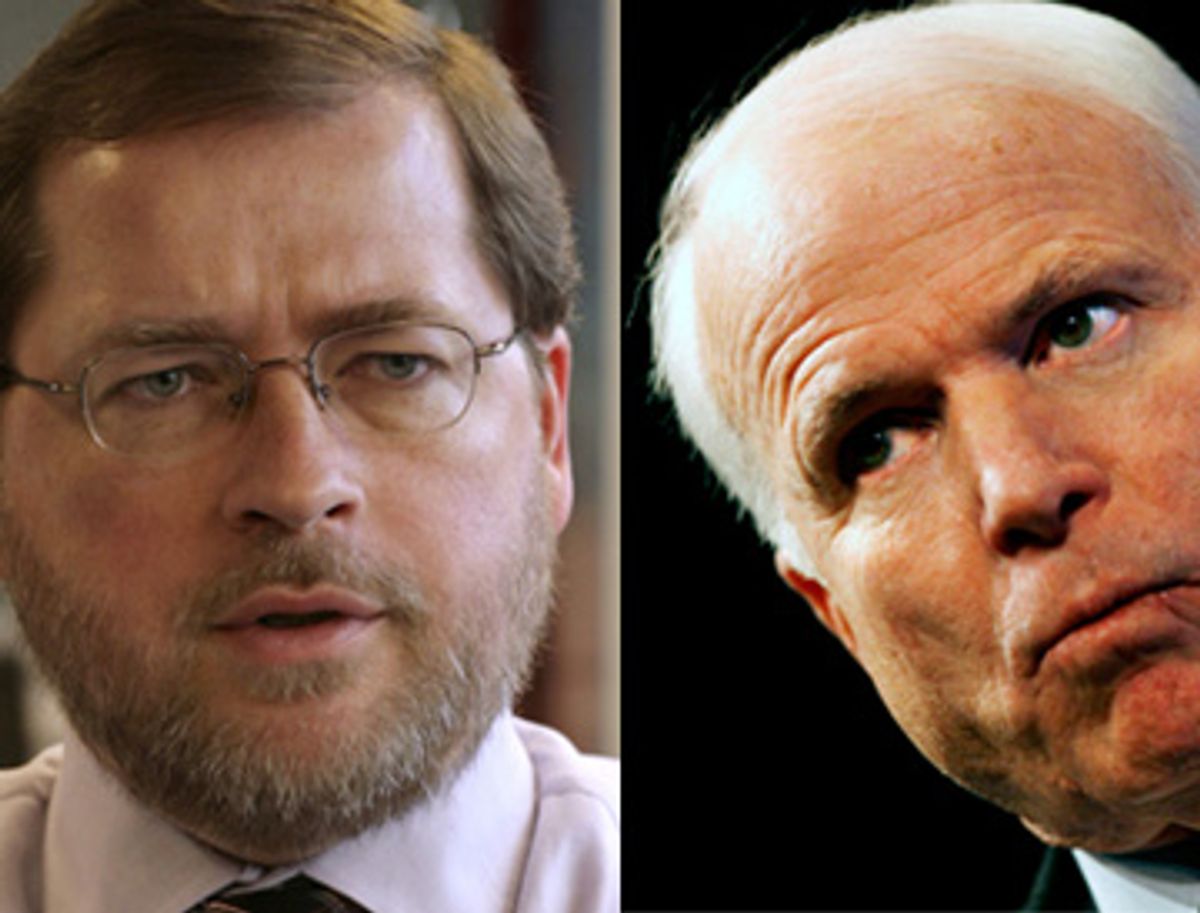

Republican activist Grover Norquist raised questions Monday about the viability of John McCain's presidential ambitions if McCain sticks with his decision to forgo signing a written pledge promising not to raise taxes.

"It is difficult to see someone running successfully for the Republican nomination," said Norquist, "with a six-year record of being against Reaganesque tax cuts and then not signing the tax pledge." Norquist, who vigorously opposed McCain's last presidential campaign, was referring to President Bush's 2001 and 2003 tax cuts, which McCain opposed at the time.

Norquist added that he believed McCain would eventually change his mind and sign the pledge. "I will be very pleased when he does," Norquist said. "No harm, no foul."

On Thursday, McCain told reporters during a bus ride in Iowa that he had no plans to sign the so-called Taxpayer Protection Pledge authored by Norquist, a Republican activist with whom he has tangled repeatedly.

The pledge, which commits the signer to opposing any increase in marginal income tax rates, has become a mainstay of Republican Party politics since its debut in 1986. It earned the signature of 1996 GOP presidential candidate Bob Dole and President George Bush in the 2000 campaign. In a humorous aside last week, McCain joked that the Norquist pledge was "up there with the Magna Carta" in the reverence it inspired. According to Norquist, McCain signed the pledge as a candidate in 2000.

But last week, McCain said he would not sign the pledge again. "I don't think I am required to sign any pledge of Mr. Norquist's," McCain said. "My record is very clear. I have never voted for a tax increase in 24 years. That should be sufficient time to convince average Americans of my commitment not to raise taxes." A McCain spokesman reaffirmed that position on Monday.

To date, only two major candidates for the Republican nomination have not signed the taxpayer pledge, McCain and Rudy Giuliani. Norquist has repeatedly praised one of McCain's rivals, Mitt Romney, for being the first candidate to sign the pledge in this election cycle. Several weeks ago, Norquist introduced Romney at a gathering of conservative activists in Washington.

In an e-mail statement to Salon, Romney spokesman Kevin Madden predicted that McCain's decision could harm him. "Candidates who won't take a pledge against tax hikes, who also voted against the 2001 tax cuts, will have a lot of explaining to do to Republican primary voters," said Madden.

McCain now says that his votes against the Bush tax cuts in 2001 and 2003 arose from a disagreement about what kind of tax cuts were needed. McCain later supported a 2006 extension of some of the Bush cuts, and says he now thinks all the cuts should be extended when most of them expire in 2010. This has not been enough to mollify some conservative critics, including the Club for Growth, which called McCain's overall record on taxes "profoundly disturbing and anti-growth." The club's president, Pat Toomey, said he is particularly upset by a 1998 vote by McCain to increase cigarette taxes.

"If he has signed the pledge before but now suddenly is unwilling to sign the pledge, what has changed in his mind?" asked Toomey. McCain has criticized the Club for Growth in the past for opposing Republican incumbents, including former Rhode Island Sen. Lincoln Chafee, whose loss in 2006 cost Republicans control of the Senate.

For weeks, Norquist has been telling reporters that he expected all of the Republican presidential candidates to sign his pledge. "I was under the impression that he would sign it," Norquist said of McCain. He said he based that impression on a recent breakfast with two of McCain's top economic advisors, Kevin Hassett, of the American Enterprise Institute, and Doug Holtz-Eakin, former director of the Congressional Budget Office.

Hassett, who calls Norquist an old friend, told Salon on Monday that he did not offer any hints over breakfast about McCain's position on the pledge. "I don't remember conveying in either way that John would or would not sign the pledge," Hassett said.

In the interview Monday, Norquist compared McCain's decision not to sign the pledge to the rationale of a misbehaving husband. "I would never consider committing adultery, dear, but I don't want to put it in writing," Norquist said, mocking the position. "Really, why not?"

A moment later, Norquist said he held no ill will toward McCain. "None of this is personal on my end. It's all about the taxes."

This is not the first time Norquist and McCain have found themselves at loggerheads. During the 2000 campaign, Norquist was a vocal opponent of McCain's candidacy, holding press conferences in New Hampshire and South Carolina to denounce McCain's support for campaign finance reform. Norquist's nonprofit, Americans for Tax Reform, ran issue advertisements that echoed the talking points of then-candidate George W. Bush. The ad called McCain "the only candidate approved by the liberal New York Times" and suggested that Bill Clinton and "Big Labor" supported McCain's positions.

More recently, McCain was instrumental in investigating the illegal lobbying practices of Jack Abramoff, a close friend and former business associate of Norquist. A report released by McCain's staff detailed the intricate role Norquist played in Abramoff's lobbying operation. In e-mails released by McCain, Abramoff described Norquist as a "conduit" for his lobbying money. Abramoff also described Norquist's practice of accepting donations from American Indian clients in exchange for his services, which often concealed the true source of the funds. Though Abramoff is now in prison, Norquist has not been charged with any crime.

Shares