I flew down to Las Vegas last week to see a historic 32-story casino dynamited. I thought I could extract a little universal meaning from the event. Although I hail from the peace-loving town of Berkeley, Calif., I've also seemed to inherit that American male gene that makes us love seeing stuff blown up. Apart from whatever deep thoughts the experience might provoke, I was sure I'd love the show.

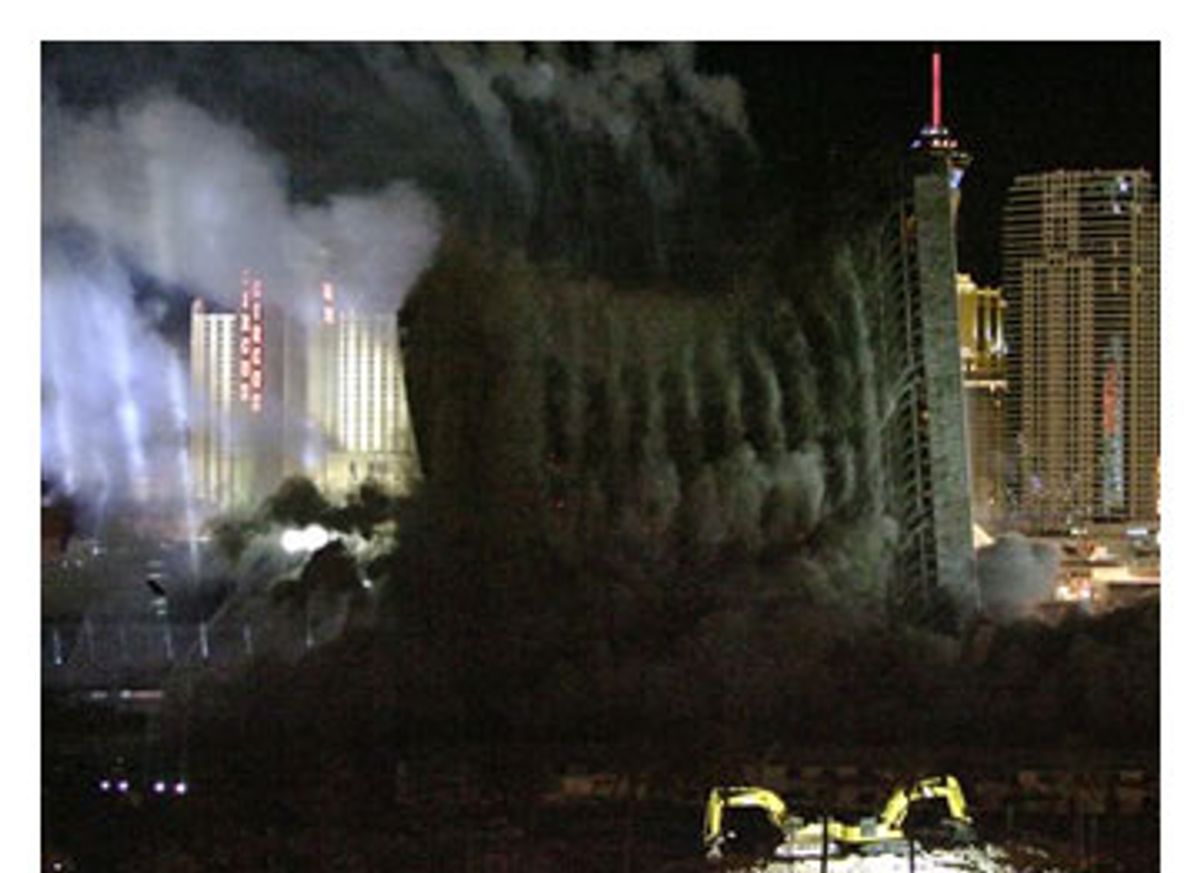

I did enjoy it, though the hours of standing around in the Strip's outdoor haze of cigarette smoke and diesel fumes didn't seem like a fair trade for 30 seconds of hot man-on-building action at 2:30 in the morning. The climax, after a four-minute fireworks show, was two quick rounds of explosions that sent the hotel tower and an adjoining nine-story inn at the old Stardust resort crashing to the desert floor. All that mass slamming to earth made the ground shake and unleashed a roiling cloud of cement dust. The throng, such as it was -- a smattering of bereaved Stardust fans and former employees, plus a few random stragglers who had wandered up the Strip for the night's best free show -- scurried away. Sporting a dust mask I'd bought for two bucks from an entrepreneurial fellow spectator, I trudged back to my smoke-free hotel, looked at the pictures and video I'd shot, and went to sleep.

So the Stardust is gone except for the cleanup. There's a little nostalgia out there for the old place if you go looking for it. I understand the former workers' sense of loss; the place that fed them and their families has been erased. It's a little harder to fathom the wistfulness, expressed by some natives and by former Stardust guests, for the old Las Vegas they say the Stardust represented. It was maybe a friendlier and classier place, in the sense that Frank Sinatra and pals represented chumminess and class; a place that was a little more humane in scale and perhaps more affordable without maxing out your credit cards.

It's true the Stardust was older than most Strip hangouts: It dated to 1958, the tail end of the first building boom on the south end of Las Vegas Boulevard. When it opened, it boasted the biggest casino floor, the most hotel rooms (some at $6 a night) and an absurdly large swimming pool. It's true that it drew lots of colorful characters and provided both a playground and a steady payday for real-life mobsters. For a while, it was world headquarters for Wayne Newton. It hosted Don Rickles, who at 80 survives the Stardust on another nightclub stage nearby.

But with all due respect to the recently departed, that Stardust and that romantic Vegas vanished into the desert about the same time the casino business went corporate, decades ago. The Stardust itself was a model of that change: Physically, it grew out of its original sprawl of low-rise barracks into bigger and swankier quarters. The hotel tower reduced to dust last week was put up in 1991 as the resort's owner, Boyd Gaming, struggled to keep up with the Strip's new generation of super-sized gambling and entertainment palaces.

From the outside, the structure was, without its bars of indigo and scarlet neon, as featureless and functional-looking as a warehouse. So, yes, it's not easy for a hard-hearted outsider to work up a lot of emotion over a building that dated all the way back to the day before yesterday. As far as old-style Sin City class and affordability, the Stardust mourners can always drop by the Frontier, the next stop south of the Stardust, where you can get a room for 45 bucks and catch bikini bull riding three nights a week.

The truth is, sad as it may be for those who can sit in a Las Vegas bar and conjure up Frank, Dino and Sammy strolling in the door, the loss of one more name from Las Vegas' past is far less arresting than what has been happening up and down the Strip. Resort owners and investors, driven to compete with each spectacular new arrival -- the Wynn, the Bellagio, the Venetian, Paris -- have been knocking down buildings and putting up new ones at a ferocious pace. By one count, crews have dynamited 15 hotel buildings, including the two at the Stardust, in the last 14 years. The oldest structure imploded, the Stardust's nine-story inn was 42 years old. The newest was a 7-year-old tower at the Desert Inn. The average age of the imploded hotels: 21 years, three months. Your local rent-a-space building is likely to get a longer run.

Landing in Las Vegas the afternoon before the Stardust had its last big moment, I spotted it well to the north. Stripped down to its concrete-and-steel skeleton, though, it was a little hard to pick out from the forest of new buildings and construction cranes rising nearby. The Wynn is putting up a second tower, called the Encore, just across from the Stardust site; a bit to the south and west, Donald Trump is erecting his trademark horrific gold-mirrored slab; and back on the Strip, still further south, a colossal new hotel, the Palazzo, is going up next to the Venetian. At the Encore and Palazzo, the construction is going on 24 hours a day. There's a hurry to get them open and get them pulling in crowds and cash.

Looking at the gently lit Stardust tower after sunset, glancing at the new buildings rising nearby and at all the massive, crowded hotels up and down the boulevard, it was clear they're all of a piece. That night, it was the Stardust's turn to make way. Already, the town's Strip watchers are guessing which hotel will go next. Looking around, it's almost as if every building you can see -- established, brand-new, under construction -- is on the knockdown list. The ground is that valuable. The crowds arriving to spend their money on something bigger and better are that big. That's Las Vegas.

Soon, something bigger and better will fill the blasted 63 acres where the Stardust stood, too. Specifically, Boyd Gaming's Echelon Place. The name's got as much romance in it as you'd find in the average Pentagon file drawer. It will be a $4 billion mega-resort with four hotels, 5,300 guest rooms, a shopping mall, a convention center, a couple of theaters, and two dozen restaurants. It's supposed to open in 2010, and then a new generation of newlyweds, convention-goers, gamblers, vacationers and employees will start fashioning memories they'll share on that not too distant evening when they gather to watch the whole thing come down.

Shares