To listen to a podcast of the interview, click here.

To subscribe: Click here to add Conversations to iTunes or cut and paste the URL into your podcasting software:

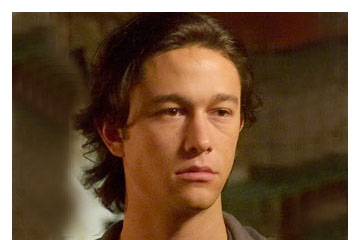

Joseph Gordon-Levitt has been acting professionally for 18 of the last 20 years, which would be a remarkable statistic for someone twice his age. But he’s 26, and has made the highly unusual transition from adorable child star to complicated and even dark adult actor.

Essentially, Gordon-Levitt has had two different and almost diametrically opposed acting careers. He began appearing in films when he was just 7 years old, but attracted wide notice for his role in Robert Redford’s “A River Runs Through It,” released in 1992 when he was 11. Then came an extensive cute-kid television career, on “China Beach,” “L.A. Law,” “Quantum Leap,” “Roseanne” and 66 episodes of “3rd Rock From the Sun,” in which he played Tommy Solomon.

His second career began in earnest in 2001 with the little-seen indie film “Manic,” in which Gordon-Levitt played a violent, institutionalized teenager. Although the cute kid had grown up into a strikingly handsome young man, he didn’t seem innocent or wet behind the ears anymore. Abruptly Gordon-Levitt emerged as one of the most interesting leading men in independent film, a thoughtful performer, simultaneously outspoken and introverted, who specializes in playing troubled characters at war with themselves and the world. (He also has his own Web site, which he describes as his “alternative outlet of where I get to be a little less professional and just freak out a little bit.” Click here to watch one of his shorts.)

Filmgoers first noticed the new Gordon-Levitt for his highly charged role as a haunted and morally ambiguous gay hustler in Gregg Araki’s cult hit “Mysterious Skin,” and then he stole the show as the hard-boiled high-school detective hero of “Brick.” I met him in a hotel suite in Austin, Texas, where his new film “The Lookout” was premiering at the South by Southwest Film Festival.

A stark, shifty thriller written and directed by Scott Frank (screenwriter of “Out of Sight” and “Little Man Tate,” among other films), “The Lookout” is the closest thing to a Hollywood film Gordon-Levitt has made in his second career. Still, it fits the pattern: He plays Chris Pratt, a one-time high-school stud athlete who’s trying to recover from the physical, psychological and emotional effects of a disabling brain injury (one caused by a hideous car crash that was his fault). Chris becomes the focus of a group of predatory gangsters, hoping to use his disability and vulnerability to help them rob the bank where he works as a janitor.

Gordon-Levitt greeted me in his hotel room with excessive politeness, clad in a prep-school-neat shirt and tie that made him look like a new wave guitarist, circa 1982. He was friendly and seemed eager to have a real conversation, but has already learned the guardedness that comes with being a celebrity. It applies even to the minor-key celebrities, the self-debunking and self-deflating ones, the ones who have walked away from one kind of stardom in search of a more grown-up one.

You played the damaged, charismatic strange guy in “Mysterious Skin,” and then the hard-boiled teenage detective in “Brick,” and now you’re playing a guy who’s recovering from a serious brain injury. It’s like everything has to have enormous challenges.

Well, life is challenging. I think movies without a little darkness are boring, because the world ain’t like that.

But I suppose you’re going to tell me that, despite all these characters, you’re a completely normal, likable guy.

Oh, far from it. No one likes me. Will you be my friend? [Laughs]

I don’t know. You seem like a dangerous character.

Be careful.

So what was it that drew you to this role? I know this project has been kicking around. Leonardo DiCaprio was going to be in it. David Fincher was going to direct it. What drew you to it?

Simply a good script. At first, this is what draws me to any movie. It sounds obvious but it’s unfortunately very rare to find a script that’s got some really good writing to it. I think our movies in general are being controlled by people who think that special effects and gimmicks are going to sell more tickets than a good story. I think they’re wrong. Scott Frank, who wrote and directed “The Lookout,” knows how to tell a story, and it was immediately apparent when reading the script. And he’s an inspirational guy. He’s really passionate about what he does; that’s what I’m always attracted to — passion and love. I was lucky to get to work with him.

I remember Rian Johnson talking about you preparing for his movie “Brick” and how you would try to do all this work to figure out the difficult dialogue in it. What were the challenges as far as getting ready to play this guy?

Preparing for “The Lookout” was obviously focused a lot around what would it be like to have a traumatic brain injury. But as I did my preparation and research, and hung out with people who had been through accidents and situations similar to Chris Pratt and suffered injuries similar to the one portrayed in the movie, I found that not only is everybody an individual but the boundaries that we draw between the “us” and the “them” are actually really faint. It grew apparent to me that I wanted to make Chris certainly have his new life and condition be present at all times, but actually I wanted to point out the similarities between him and someone without a traumatic brain injury more than I wanted to point out the differences.

It’s definitely not one of those roles where you’re thinking about the person’s disability all the time.

Right. That’s what I found. When I was hanging out with these guys who were “disabled,” it was only in isolated moments when that would really surface and the rest of the time you’re just hanging out with somebody like you’d be hanging out with anybody else.

And it seems like you hit on the idea that one of the main things that manifests for Chris is that he gets angry when he’s not able to do something the way that the so-called normal part of him would want to. Was that one of the key things for you?

It’s true, there’s two edges to an injury like this. There’s the injury itself, which does change your brain, but then I think the even more severe and painful truth of the condition is that he remembers who he used to be and wishes so badly that he could be that and isn’t. So it makes him insecure and it makes him feel bad about himself, and that’s way more painful than not being able to have your brain work like it used to — way more painful. I think that’s something he has in common with everybody. Everybody’s fears and insecurities, those are the real demons. The problem is when you’re scared. The problem is when you don’t love yourself. And Chris has a healthy portion of lack of self-love, and that’s what’s really holding him back, I think, even more than the brain injury.

If you’re talking about his lack of self-love, isn’t that what also makes him vulnerable to these people who want to take advantage of him?

That’s exactly it, and I think they at first want to take advantage of him because they know he has this injury, but as they get to know him they see that really what they’re taking advantage of is just a sad and lonely guy. That’s what’s so vicious about the villain, Gary, is that Gary doesn’t know anything about traumatic brain injury but he does know about people. He knows how to play somebody, and he does so to intense effect.

Scott Frank makes these genre films, but they’re really based in the reality of what these people are like.

That’s ultimately why I loved the script so much. I can see whole people in the pages. A lot of movies, every character is kind of this one-dimensional device: This is the good guy, this is the bad guy, this is the girl. It’s so boring, and people aren’t like that. Life isn’t like that. Life’s not simple. Nothing is black and white. And I don’t know why people think that black and white makes good stories. It doesn’t. It makes boring stories. You know what’s going to happen. The way Scott writes, yes, there’s a hero and a villain, but it’s a little more complicated than that, and that’s what keeps you interested in watching.

Given your recent performances, you’re going to get offered parts in films that are a little bit more black and white in terms of their structure and that maybe also pay really, really well. Are you really going to be able to say that you don’t want to do those kinds of movies?

I just want to do good movies, and by the way, “The Lookout” paid really well.

Well, good. I’m glad to hear it.

I’m so lucky to have a job like this. It’s funny to me when I hear actors talk about “littler” movies like “The Lookout.” “The Lookout” is a huge movie! It cost like $20 million to make! Come on. The point is not how much it cost to make or what corporation backed it, the point is that it was a good script and that the people making it loved what they were doing. It doesn’t matter what the budget or what the corporate structure is if you have that kind of love and that kind of integrity. So if you ask me what I’m going to do next, I’m going to do the same thing: I’m going to try to find movies made by people who love what they’re doing, who have something to say, who know how to write, and hopefully it will turn out good.

How did you start on this track of movie acting? Were you one of the kids who was acting in school theater starting from an early age?

I’ve been acting professionally since I was 6 years old. I actually just hit my 20 years.

Not too many people who start as little kids are able to keep doing it as adults so that’s an accomplishment in itself. You obviously never got sick of it, though.

I did. I quit for several years actually. In fact, that number 20 maybe isn’t exactly true because I did quit for about two years.

Did you consider other careers?

I went to college. I wanted to have a wide-open future with endless possibilities. [Laughs] It wasn’t so much that there were other careers in particular that I was considering so much as I just wanted to stop acting. I really wanted to move away from home and go to college, and I think it’s the smartest thing I ever did. Moving to a new place and seeing how you fit in without any of the crutches that hold you up in the old place is so good for the soul, I think, and it was good for mine. Ultimately it brought me back to acting, but I had to find that for myself.

So when you got back to acting, was there a transition between the old acting career and the new one or did it feel like the same thing?

It was different. It took a while to find a filmmaker who would believe that I could do something other than what I was known for doing, because the Hollywood structure was not going to believe that. It’s against its principles to go against the formula like that. But Jordan Melamed, who made “Manic,” Gregg Araki, who made “Mysterious Skin,” Rian Johnson, who made “Brick,” and Scott Frank, who made “The Lookout,” all of them kind of flew in the face of what most people thought of me and believed that I could do anything I wanted to.

Are you working on another project now?

I shot three movies last year. “The Lookout” is the first one that’s come out. Then there’s going to be “Killshot” and a movie that is probably going to be called “Stop Loss.” All three of them are really cop-intense, violent movies in a way. This one is a heist. In “Killshot” I play a killer next to Mickey Rourke, and then in “Stop Loss” I play a soldier. It was a hard year. It was a good year. I feel like more of a man.