To listen to a podcast of the interview, click here.

To subscribe: Click here to add Conversations to iTunes or cut and paste the URL into your podcasting software:

Long one of rock's most darkly charismatic figures, Nick Cave has filled his career with songs that married an almost biblical sense of morality and justice to an evocative, highly literate lyrical style that marked him as sort of a louder, angrier Leonard Cohen. Cave's new album, recorded under the name Grinderman (and without his longtime backing band the Bad Seeds), finds the Australian singer-songwriter, who turns 50 this year, making some of the noisiest, harshest music of his career. The reasons for the added aggression? He's getting old and, if songs like "No Pussy Blues" are any indication, he's not getting laid.

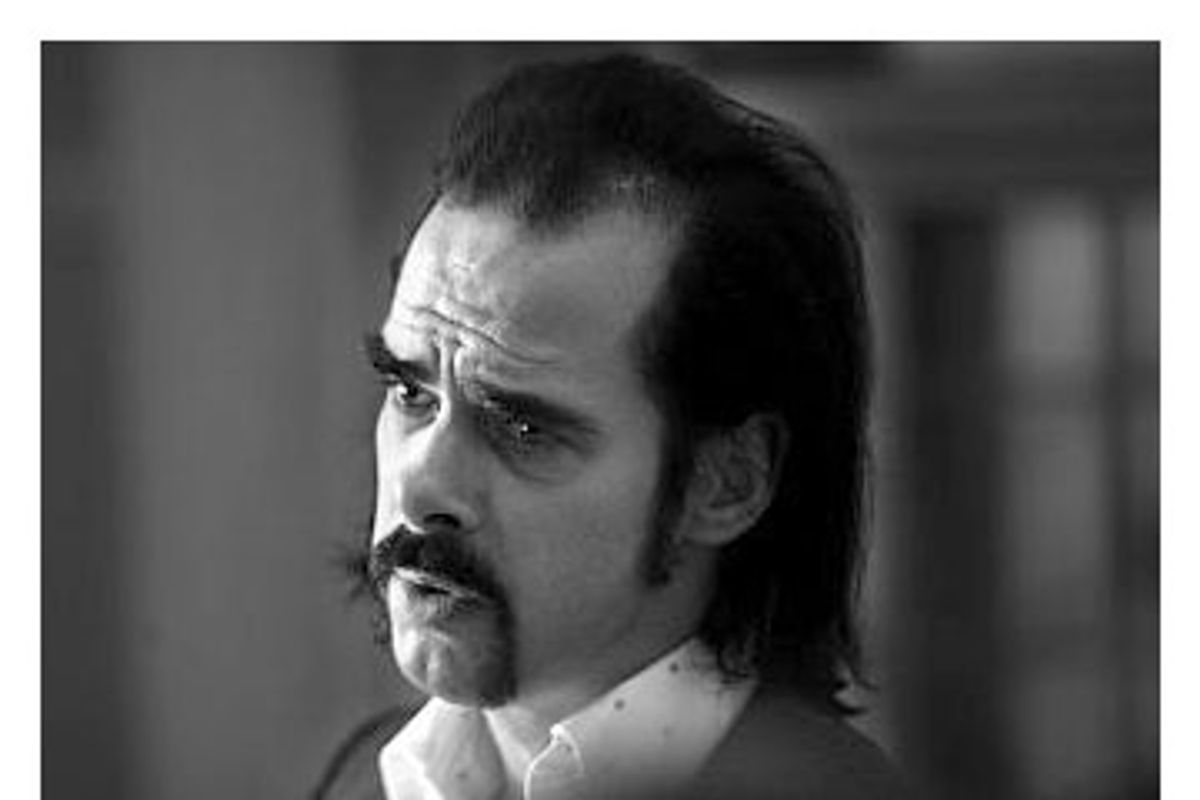

Rail thin and dressed all in black, with a long handlebar mustache hugging the sides of his mouth, Cave -- accompanied by Grinderman drummer Jim Sclavunos (hear them both in this podcast) -- cut an imposing figure as he spoke with Salon about an album that he says came out of a "monumental midlife crisis."

There's a sexual frustration that permeates the album -- and this is the year you turn 50.

Absolutely. I'm about to turn 50 and sex preoccupies you the older you get. You're a young guy, you don't know about that. I think you become invisible. I suspect the older you get the more invisible you become.

Invisible in what sense?

To the world. The less impact you really have. You're not seen in the same way. This record's actually about a person who's physically disappearing. There's a song, "Love Bomb," where he keeps looking at himself in a mirror and he's becoming thinner and a girl reaches out to touch him and her hand goes right through him. I think, as you get older, you become more and more invisible and then you die.

So why get up in the morning?

Because what we're doing, as far as I'm concerned, is doing something. The least we can do is put out something that inspires people and can be genuinely uplifting in some way. Every day in the papers, without getting too drawn into specifics, there's mounting evidence that the direction we're going in is wrong and we're heading for major catastrophes in a lot of different areas. If one thing doesn't get us, something else is going to, and it doesn't look like that's too far away. You would think that the powers that be would shift their focus slightly and try to remedy this, but that hasn't happened and I guess that makes you feel a little bit impotent.

I think there's also for me, as I get older, a feeling that as an individual whatever impact I'm going to have is done; I've had it. This actually is a cause of celebration for me, and liberating, because I can just go and do whatever the fuck I want.

You've talked about listening to a John Lee Hooker song and hearing the lines "I went down to my baby's house/ I sat down on the step," and how they opened up the album for you.

Yeah. You're toying around with different ideas and you want something ... I'm doing this at the moment with the Bad Seeds record and there are these half ideas floating around in fucking aspic or something, floating around in space, and suddenly you just get this thing and you know what it's about and these things can collect around a basic idea. I had some ideas and those two lines came out when I was listening to this John Lee Hooker song trying to work out how he played guitar.

Those seem like such innocuous lines.

Not to me.

Can you explain why?

There was a sense of disengagement between the man and the woman. You don't go around to your baby's place and then sit down on the step. There was something so beautiful to me about that. With the Bad Seeds, when I write songs, they're very often about a man and a woman sitting and looking at the world and the world's going to shit in a handbasket and all that kind of stuff, but there's this connection and love will save the day. I guess that this was something else, where the woman on the Grinderman record has been released and has flown off to do whatever she wants to do and the man is there imprisoned in some way -- that's what that meant to me.

Look, when I'm alone and writing there are all sorts of influences -- feminine and masculine influences, memories and ghosts of the past, all that stuff -- having an impact on what I write. With Grinderman, most of it, I'm stuck in a room with four guys in the middle of a fucking monumental midlife crisis. It's a male thing. It's an old man kind of thing. I think there's really something kind of hysterical in the music that's a reflection of that.

So now you're going through a midlife crisis and --

I was being slightly ironic.

So you're dealing with these issues, and the sound of the album is wilder and looser than it's been in a while.

[Cave snickers]

No? Musicians just don't like to be told what they sound like! But your early music was also maybe written at a time of sexual frustration ...

Well, actually, no. In the "Birthday Party" days it was pussy on tap. You had to beat it away with a stick. Are you saying that the music sounds like something we would have done when we were younger?

Yeah.

I reckon the music sounds something like, you know when you go to a disco and you see some middle-aged guy getting down? It sounds like some dad guy having a few drinks and going nuts in a disco. The young kids are loving it, we're getting all this response from the kids, but we certainly weren't trying to recapture some lost youth.

You were right, though. We just don't like to be told where our music's going. So get fucked. [Smiles]

How important is the concept of morality to your music?

I wish I could get away from that. Maybe not so much now, but I used to write in a narrative form of songwriting, which required a kind of conclusion at the end, or a summing up of what the story was about with a kind of moral perspective. It comes from there. I hope you don't listen to my stuff and think I'm trying to persuade you. That's never the intention.

-- David Marchese

Shares