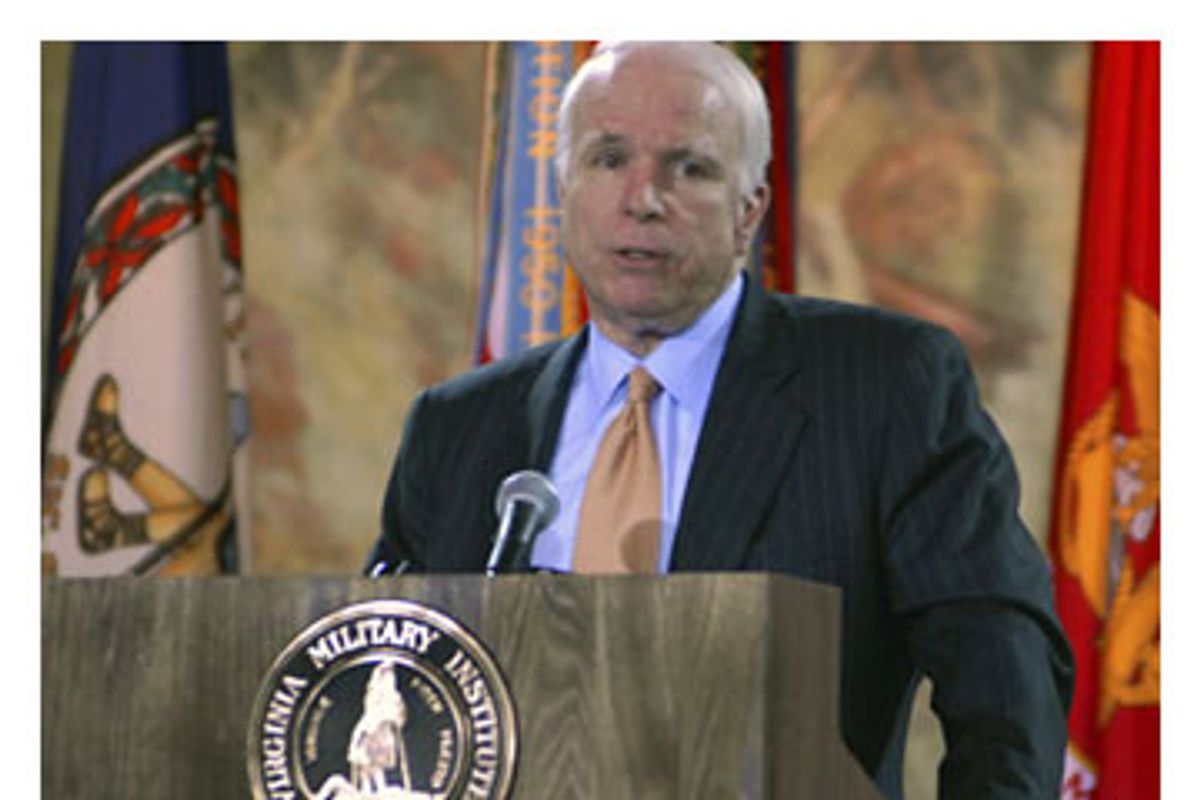

Arizona Sen. John McCain stood before an auditorium of uniformed cadets at the Virginia Military Institute in Lexington, Va., on Wednesday with a message about the war in Iraq. "There are the first glimmers of progress," McCain said, in what his campaign billed as the first of three major policy speeches that will lead to the official announcement of his presidential campaign later this month.

McCain was reading the words off a teleprompter in the back of the room, but it was hard not to notice how closely they matched a statement made just 25 hours earlier by President Bush, who had also come to Virginia to talk to a military audience. "We're beginning to see some progress towards our mission," Bush had declared to American Legion Post 177 in Fairfax.

The echo-chamber effect did not end there. On Tuesday, Bush told his listeners that the Democratic leadership was "irresponsible" for attaching restrictions on funding for the troops, which Bush called a "political statement" that could risk the war effort. On Wednesday, McCain told the VMI cadets that Democrats had chosen a "reckless" road that would "deny our soldiers the means to prevent an American defeat." On Tuesday, Bush praised Iraq's new oil law, warned of a power vacuum that would be caused by a U.S. withdrawal, and spoke of the lessons of Sept. 11. On Wednesday, so did McCain.

Seven years ago, no one would have guessed that Bush and McCain would be working off the same set of talking points in the same states just one day apart. Back then, Bush and McCain were bitter rivals locked in a nasty battle for the Republican nomination, which left a legacy of lingering resentment. But as McCain endures a struggling start to his campaign to follow Bush to the White House, the Arizona Republican has chosen to tie his fate to an unpopular military plan developed by a sitting president with an approval rating in the mid-30s. McCain says he has no illusions about the fact that his campaign may hinge on the military success of Bush's plan in Iraq. "Irony of ironies," McCain told reporters several weeks ago, on a campaign swing through Iowa. "Life is not fair."

Rather than downplay the irony, McCain has chosen to embrace it, encouraged by polls that show a majority of Republican primary voters still support the military strategy in Iraq. As a result, McCain has become President Bush's most prominent -- and perhaps effective -- pitchman for continuing American involvement in Iraq. Unlike Bush, McCain is a combat veteran and endured more than five years as a Vietnamese prisoner of war. Unlike Bush, McCain has carefully nurtured a reputation for "straight talk," which includes years of blistering criticism of Bush for his faltering military plan in Iraq. And wherever he goes, McCain attracts press attention that approaches that of Bush, as was evident this month when McCain traveled to Iraq and declared that the security situation had improved. "It is my obligation to give it a chance to succeed," McCain said Wednesday, about the current military strategy. "To do otherwise would be contrary to the interests of my country and dishonorable."

This strategic gambit is remarkable not just for its obvious electoral risks in the general election, but for the fact that no other Republican candidate has yet to race so fervently into the breach. The two other so-called Republican front-runners, Mitt Romney and Rudy Giuliani, both say they support the president's plans for escalating troops into Iraq. But they also both take pains to keep their distance from the president's plan, rarely describing it in detail during campaign stops. At a "national security" speech on Tuesday in Texas, Romney brushed over his support of the Iraq war plan in a few quick sentences, before retreating into the far more comfortable terrain of foreign policy abstraction. "In my view, our objective is a strong America and a safe world," Romney said, before offering a proposal to increase the size of the overall military by 100,000 troops.

Other long-shot Republican candidates have kept a greater distance from the president's Iraq policy. Kansas Sen. Sam Brownback opposes the current escalation of troop numbers in Iraq. Former Arkansas Gov. Mike Huckabee seems more confident speaking about high school music classes than the war. When asked, he often dodges the question by saying that he does not have the same information as the president to evaluate the situation in Iraq, though he adds that he supports the president's policy. Nebraska Sen. Chuck Hagel, another possible presidential contender, has called for a timetable to disengage from Iraq.

The leader of the military campaign in Iraq, Gen. David Petraeus, says it is still too early to tell if the escalation of the American military presence in Iraq is succeeding. The "surge" was announced in January, but new sweeps in Baghdad only began in mid-February. President Bush says that only about half of the additional U.S. troops he intends to send have arrived in Baghdad. In the meantime, little has changed on the ground. The Iraqi government reports that violent civilian deaths climbed to 1,861 in March, up from 1,645 in February. On Monday, the New York Times reported 116 hostile deaths of American soldiers in the seven weeks after the escalation of troops began, compared with 113 deaths in the seven weeks before.

McCain alone seems willing to mimic Bush's talking points -- but he also tempers them with criticism of the president and a more prominent acknowledgment of the tenuousness of the situation in Iraq. In his speech Wednesday at the Virginia Military Institute, a state-run school for military officers, McCain offered several qualifications to his assessment of Iraq. "The hour is late," he said, "and despite the developments I just described, we should have no illusion that success is certain."

McCain also took several swipes at President Bush and Vice President Dick Cheney, who have long described Iraq in rosy terms -- "last throes," "dead-enders" -- that have repeatedly proven to be false. "I understand, and you understand, the damage false optimism does to public patience and support," McCain said. "I learned long ago to be skeptical of official reports that are long on wishful thinking and short on substance."

Polls suggest that the American people have also learned this lesson, which makes McCain's task much more difficult. He has become the new salesman for the latest version of a failed product. As such, he may no longer control his own political destiny.

Shares