Across America, 2007 is shaping up as the year the death chamber forgot. All but two of the 15 executions to date have been carried out in the historically death-penalty-friendly state of Texas. The current turn of events comes as no surprise, given that the national execution rate has dropped by half since 1999 and the total number of executions hit a 10-year low in 2006. Several states have halted executions until concerns about the cruelty of lethal injection can be addressed, and even some Texans are getting squeamish. Last month the conservative Dallas Morning News reversed its century-old, pro-death penalty posture.

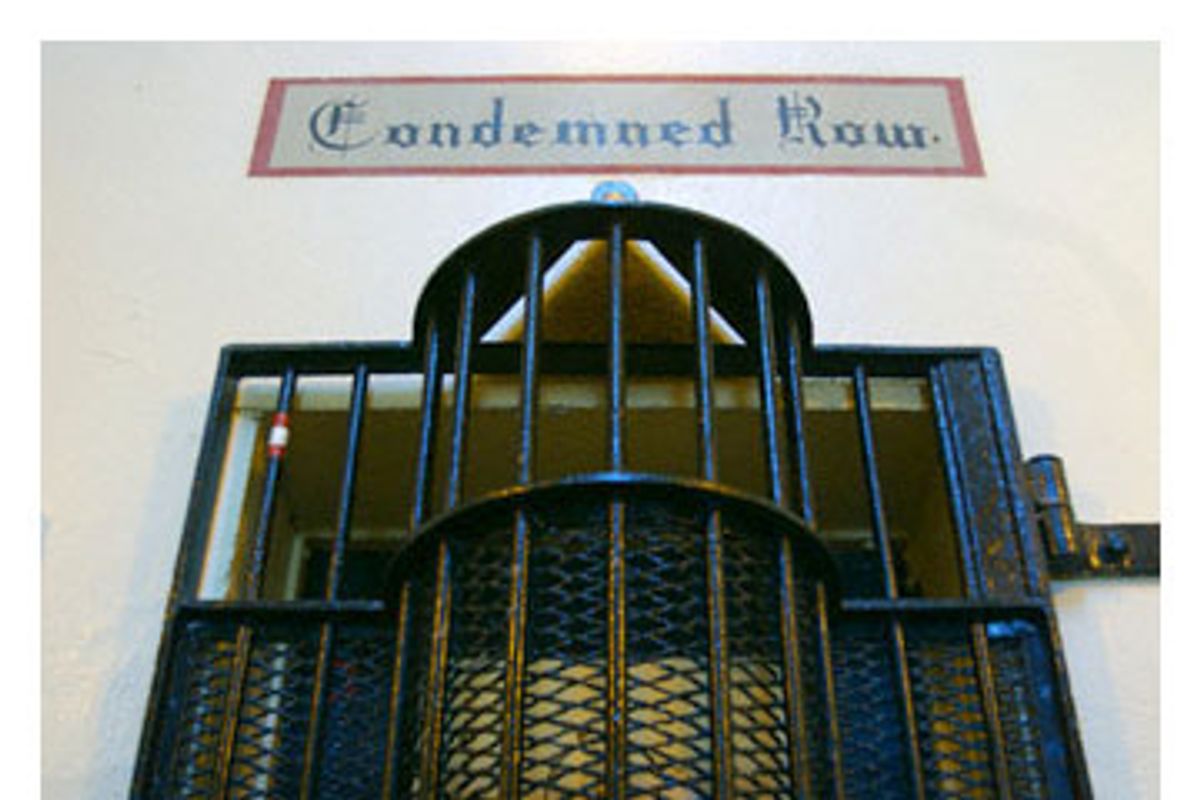

Which made it all the more puzzling when California Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger's corrections team began building a new death chamber. The existing structure, situated at storied San Quentin Prison on a bluff overlooking the San Francisco Bay, is a relic from the era of death by gassing. It is darkly quaint, in a "Life Aquatic" kind of way, with Gothic lettering over the entryway and Frankenstein bolts on the death tank windows. The quarters are tight and the lighting is dim, and the governor's team ostensibly reasoned that a new chamber would appease the judge who imposed a temporary statewide execution ban in December. The new chamber, built adjacent to the old, includes a holding cell, an area to mix the injection drugs, and three spacious viewing rooms. The latter despite the fact that the judge's concerns, like those of judges and lawmakers in other states, were more focused on the ill-conceived process of death by poisoning than the lack of comfortable chairs.

After a week or so of backlash from state legislators, many of them beholden to Bay Area constituents who shudder to think that death row is in their backyard, Schwarzenegger caved. He halted the $700,000 project, pending approval by the Legislature. But why would Schwarzenegger have signed off on such a plan in the first place? Does he really want to accelerate capital punishment in California, which has an execution rate of less than one death a year? Surely not, when each pending execution threatens a raft of time-consuming political headaches. At a time when both parties lay claim to the law-and-order mantle, it can't be because he needs to crank up his GOP street cred -- the governor, like nearly every other major pol across the land, has made his pro-death stance clear. Rather, the death chamber project provides political cover for another, bigger project Schwarzenegger hopes to launch, one that reflects the real state of the death penalty in California and the United States in 2007.

California is home to by far the largest death row in the United States, with some 662 men and women condemned to die. Nearly all are housed at 155-year-old San Quentin, which, like its death chamber, lags far behind prison industry standards. There are 619 inmates living in a space designed for 554. Guards say that the antiquated cells are not secure, leading to several attempted prison breaks in recent years, and prisoner rights' advocates decry the abysmal living conditions. What Schwarzenegger really wants to do is expand death row. At an estimated cost of $337 million, he wants to upgrade security and increase death row's capacity to 1,152 beds.

Despite support from both the prison guards' union and prisoners' advocates, this is not an easy sell. A revamped death row was first proposed in the mid-1990s and briefly resurrected in 2003 by then-Gov. Gray Davis. It has stalled repeatedly amid resistance from some death penalty opponents and from Marin County locals who would like to see San Quentin airlifted to the Central Valley. The Legislative Analyst's Office, a nonpartisan fiscal advisor, says the cost of the project far outweighs its value and the money would be better spent elsewhere within the state's profoundly dysfunctional prison system.

That's a valid point, but in truth, building more death row prison cells is a concession to the open secret that California's condemned inmates are rarely executed. Since the death penalty was reinstated in California in the 1970s after a brief ban by the U.S. Supreme Court, the state has sent more than 700 men and women to death row and killed 13. An equal number have committed suicide while awaiting an execution date. In all, 54 death row inmates have expired without being executed, most from natural causes. The reasons for the state's slow rate of executions are many. They include strenuous judicial review and a raft of California defense lawyers willing to fight the death penalty pro bono, as well as the attorneys and investigators in the federal public defender's office, who leave no stone unturned when an inmate is facing his final appeals. The governor is well aware of these facts. His improved prison would house nearly double the current death row population.

Across the country, the death-row-as-life-row phenomenon is spreading. A dozen of the 33 states that have conducted executions in the so-called modern era (since the penalty was reinstated in the mid-'70s) have not put anyone to death in five years. An additional six have been dark since 2005. This amounts to a sort of tacit moratorium among half the executing states.

If the California death-chamber project appeases the state's death penalty supporters while building support for a far more expensive undertaking that would enable the governor to improve life for those behind bars, then why not? Death penalty supporters would get a new death chamber, and Schwarzenegger could spend the resulting political capital making long-needed improvements in the living quarters at San Quentin. Such a project is unlikely to accelerate the rate of executions anyway.

Besides, what could it hurt to make the execution chamber as big and bright as possible, so everyone can see in gruesome detail what is happening inside? In 2002 I witnessed the execution of Stephen Wayne Anderson, a drifter who'd broken into the home of an elderly woman and shot her to death. When the prison guards led Anderson into the death chamber, I noticed that they'd shaved his head and dressed him in prison scrubs and white gym socks, but once they strapped him to the gurney, he was obscured in the dimness. From my vantage point on a creaky wooden riser, I had only a partial view of a prison staffer poking away at Anderson's arm before ripping off a rubber glove in frustration. When the execution fluids began to flow, I saw Anderson's body spasm but I couldn't hear a thing, since he and the execution team were sealed up tight in the former gas chamber. Bright, airy new quarters could eliminate this problem, ensuring direct sensory access to the inmate and the pain that results from incessant needle jabs and, ultimately, death by poisoning.

In a better world, this cruel and elaborate ritual will be abolished and San Quentin's shiny new chamber will be rendered obsolete. In the meantime, life in prison should be safe and humane, both for those who work there and for those who live there. If a new death chamber helps make that possible, so be it.

Shares