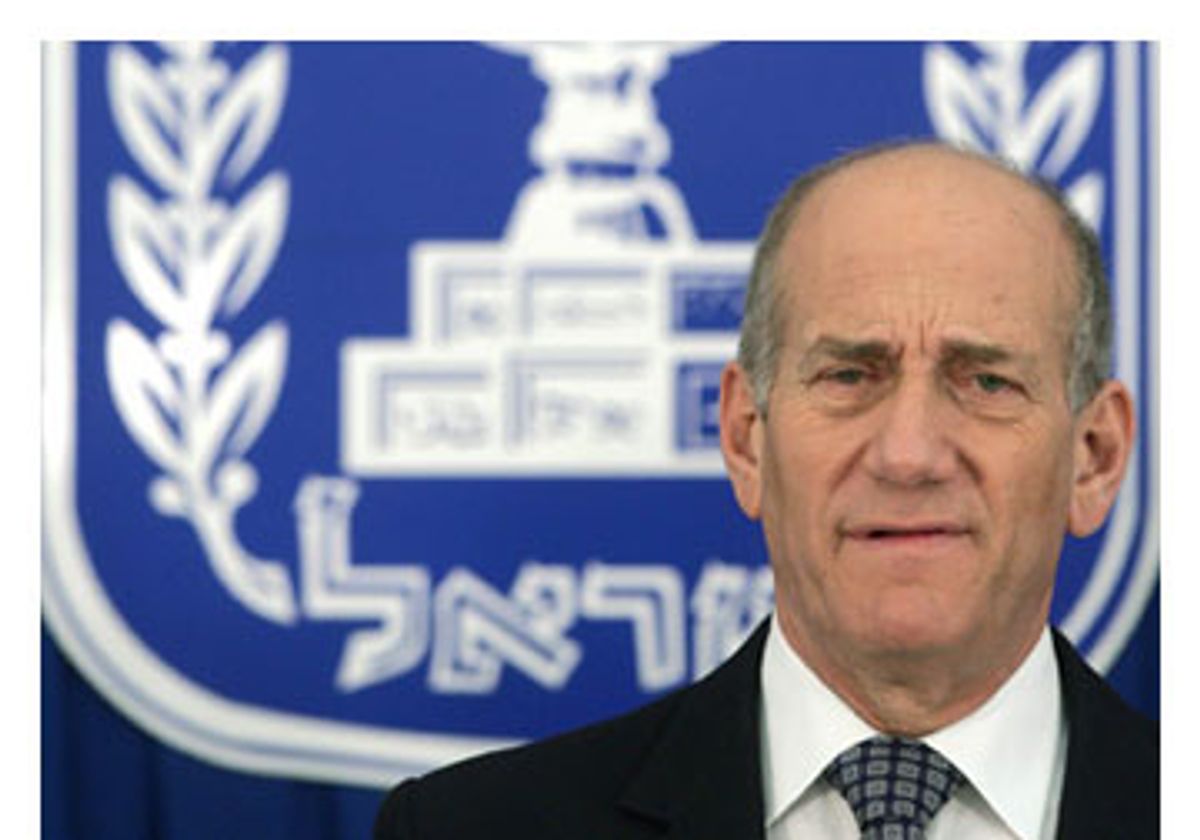

Even in a crisis-prone country like Israel, the Winograd report on the second Lebanon war, published on Monday, came as an unexpected bombshell. Israelis have a penchant for commissions of inquiry, but the Winograd Commission has broken all previously known records of national self-criticism. It concluded that Prime Minister Ehud Olmert "failed as a leader" in his hasty decision to go to war last summer. His accomplices, Defense Minister Amir Peretz and the outgoing military chief, Gen. Dan Halutz, fared no better. And this is just for starters: The current partial report covers only the opening days of the war. The final document, expected in August, is bound to be even harsher.

The severe criticisms about his leadership and Olmert's refusal to resign are, of course, making headlines in Israel. But the Winograd Commission did not criticize only the top leaders and their decision-making process. It criticized the very logic of going to war at all, without proper goals, and without sufficient operational plans and training. It cast serious doubts on the Israeli reflex of retaliation and reliance on military force.

Ironically, a key problem, according to the commission, was the perception that such wars were no longer necessary. In a carefully worded statement, the commission found that many in Israel's political-military establishment believe wrongly that the "era of wars is over" -- that Israel is strong enough to deter its adversaries and will never need to go to war again against its will, beyond fighting low-intensity conflicts like the Palestinian intifada. "By this analysis, there was no need to prepare for war, but there was also no need to seek eagerly paths towards stable, long-term agreements with our neighbors." In other words, Israel's false sense of military invincibility has been a major obstacle for peace with its Arab neighbors. If there will be no more war, then there will be no need for lasting peace. Why bother with territorial concessions when the other side is too weak to get them by force?

Israel's national security policy was thus trapped in a fateful purgatory, only to plunge into what would become its longest-ever war with a neighboring foe.

It all happened within a few hours last July 12. Around 9 a.m., Hezbollah fighters crossed the Lebanon-Israel border and abducted two reservist soldiers, Ehud Goldwasser and Eldad Regev, from a patrol vehicle. That was followed by artillery and rocket fire along the border. Olmert heard the bad news in his Jerusalem office, while he was meeting the parents of Gilad Shalit, a conscript who had been abducted two and a half weeks before in a similar manner in Gaza.

This was too much to take; barely six months in office, Olmert felt he had to prove his strength as a national leader. His predecessor, Ariel Sharon, had been Israel's top battlefield commander, but Olmert hardly did any military service. He felt that the country's enemies, Hamas and Hezbollah, were putting him to test -- indeed, Hezbollah leader Hassa Nasrallah had mocked his inexperience -- and Olmert vowed to teach them a lesson.

Olmert praises himself on his ability to make quick decisions instead of hesitating and deliberating. Here was his chance to be the new Churchill. Sharon had been traumatized by his failure in the first Lebanon war, in 1982, and during the previous five years sought to "contain" periodic Hezbollah attacks and avoid reopening the northern front. Olmert apparently believed that he could do better, and he was not held back by the haunting history Sharon had carried.

At lunchtime, reporters gathered at the inner yard of the prime minister's official residence in Jerusalem, among flowerpots of red geraniums. Olmert came out with his guest, then Japanese Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi. The Japanese leader spoke at length about Mideast peacemaking, while Olmert showed obvious signs of impatience. Peace was the last thing on his mind that day, in lieu of fierce retaliation against Hezbollah. When his turn to speak came, he announced that "our response will be very, very, very painful" for the Lebanese. "This is war," concluded the reporters who rushed to file.

And that was it. The Winograd report found no trace of serious consideration at the highest levels of government about this pivotal decision, which it likened to having taken place inside a black box.

But the unfolding tragedy quickly became national in scope. By midnight, the Israeli Cabinet unanimously approved a military plan to bomb Hezbollah's long-range rockets and other facilities inside Lebanon. The public gave overwhelming support to the government, with even die-hard left-wingers backing the massive retaliation and calling for more. Nobody stood in the way. Dissenters within the Cabinet, such as former Prime Minister Shimon Peres, whispered some concerns about possible complications but, quickly rebuffed, eventually voted with the crowd. It was groupthink at its worst.

And they were deadly wrong, concluded the Winograd report. Instead of singing the chorus, the ministers should have asked the enthusiastic Olmert and the overconfident chief of staff, Halutz, how they planned to defeat a well-positioned guerrilla force armed with thousands of rockets trained on the entire northern part of Israel. Hezbollah had prepared for exactly this kind of war for six years, ever since Israel's unilateral withdrawal from south Lebanon in May 2000. Yet the Israel Defense Forces lacked a credible, tested operational plan for the northern front. Moreover, in the fateful summer of 2006, the commission found, Israel was led by a team of rookies who lacked both experience in matters of war and intimate knowledge of the Lebanese theater.

Israeli culture is built upon improvisation. According to an old military slogan, "Every plan is merely the basis for changes." Nevertheless, this was outright negligence, the Winograd Commission said. Occupied for six years with fighting in the occupied territories against the Palestinians -- who lacked a military organization, modern weaponry or fortifications -- the Israeli army was untrained for the well-organized, well-armed force entrenched in Lebanon. But Halutz told Olmert, who visited general headquarters the day before the war, "You can trust us" to crush Hezbollah.

That was enough for the Israeli prime minister. Olmert, Halutz and others did not bother to weigh options other than a massive bombing campaign. They did not ask whether Sharon's policy of restraint and containment should be preserved, despite the abduction. They did not set credible, attainable goals for the operation. They did not conceive an exit strategy. And despite their understanding that Hezbollah would retaliate by targeting Israel's north, they ignored the implications that a barrage of rocket attacks would have "on the operational plan, its timeline or its chances of success."

Indeed, what started as a blitzkrieg-style aerial bombing developed into a quagmire. The IDF failed to destroy Hezbollah or stop the daily barrage of rockets. And despite their reluctance, Olmert and Halutz were eventually dragged into large-scale ground operations, carried out halfheartedly and with few achievements, while proving costly in lives.

The Winograd Commission, appointed by Olmert shortly after the war, was seen initially as a whitewash to fend off public criticism. But its five members, led by the 80-year-old former district judge Eliahu Winograd, took the country by surprise. They mocked Olmert's argument that his decision making was flawless, along with his declaration that the war had ended in an Israeli victory. And they ripped into the hierarchical status quo, which they said overemphasizes military considerations and gives the IDF too much influence over national policy.

Olmert has vowed to embrace the "organizational" conclusions of the Winograd report, but where will that lead Israel? In the short term, the report has thrown the country further into familiar political turmoil. Israelis were less than enthusiastic with Olmert's leadership from the beginning, giving him only lukewarm support in the March 2006 election. The failed war in Lebanon was followed by an endless string of sex and corruption scandals at the highest levels of government. At around 13 percent, Olmert's approval ratings have been the lowest in Israel's history. But Olmert has kept on, relying on a coalition of weak parties and fearing another election while having at least some floor under him from a booming economy and a decline in Palestinian terrorism. (The latter, however, is largely considered a legacy of Sharon's.)

True to stubborn form, Olmert has vowed to keep his job and overcome the blow to his already tenuous hold on power. He is doubtful of his success, but he is trying to fight anyway, arguing that the Winograd report does not explicitly call for his resignation and that his ouster would inevitably throw the country into another election. He may survive for several more months, pending his ability to ignore public protest and keep his coalition partners beside him. On Tuesday morning, Eitan Cabel, a junior minister from the Labor Party, submitted his resignation. But Cabel is a political lightweight; Olmert's fate hangs on Tzipi Livni, the popular foreign minister and Olmert's deputy. If Livni -- who got a more positive nod from Winograd for her initiative to find a diplomatic way out in the early days of the war -- jumps off Olmert's sinking ship and is joined by several more members of the Kadima ruling party, it would prove fatal to Olmert.

Olmert's downfall may lead to an early election, which would probably be another contest between two former premiers, Benjamin Netanyahu (who leads the opinion polls) and Ehud Barak, who is currently running for Labor Party leadership. Another scenario holds the 83-year-old Peres returning as an interim steward of the country. After all, the Winograd Commission favors experienced leaders, and nobody has more experience than Peres, who started his political career in the 1940s.

But either way, whatever slim hopes there were for a resumed Israeli-Palestinian peace process are doomed for now. Olmert is unable to make any real decisions, and his Palestinian counterpart, President Mahmoud Abbas, is hardly any stronger. Israelis are preoccupied with the leadership crisis; they want a leader they can trust under fire. Before the Winograd report, Olmert tried to persuade prominent members of Israel's peace camp that he was willing to go full speed ahead with the Palestinians if the left would shore up his political survival. But this appears no more than a fairy tale now, given his precarious position.

The censure of Olmert is not only ominous for the career of the beleaguered prime minister, but for the prospect of regional stability. Israel's military is warning of explosive upheaval in Gaza, or another war in the north, perhaps with Syria. And an American-led confrontation with Iran over its nuclear program is looming. The second Lebanon war convinced Israelis anew that Iran, with its rocket-armed allies and proxies in Syria, Lebanon and Gaza, is aiming toward Israel's collapse -- emboldened by America's perceived weakness in the region because of the debacle in Iraq. The Winograd Commission affirmed this analysis in its report.

Indeed, some worry that the power of deterrence stemming from Israel's military might was seriously damaged by the failure in Lebanon. The IDF lost its image of invincibility -- clearly, it is not the same military that defeated three Arab states in six days in 1967 and brought back hostages from Entebbe, Uganda, in 1976. However, the world stood idly by while Israel's air force crushed Lebanon for almost five weeks, killing hundreds of civilians and destroying roads and bridges. (Washington did, however, veto Halutz's plan to black out Lebanon's electric grid.) If Syria is tempted, or lured by Iran, to liberate its occupied Golan Heights by force, it would still have to worry about suffering the wrath of Israeli air power. Olmert publicly warned Damascus of "miscalculation," in a recent meeting with visiting U.S. Defense Secretary Robert Gates, and the threat is still hanging in the air.

Middle East wars usually erupt when nobody wants them. Following the war in Lebanon, the government increased the IDF budget, and the military launched a massive retraining program. But the perception of a leadership vacuum in Jerusalem may prompt Israel's adversaries to attack before the IDF completes its reconstruction.

Yet, dark as its conclusions are, the Winograd report gives hope in the longer term for a change in the national attitude. It calls for recasting the policy-making process and giving stronger emphasis to civilian institutions, such as the foreign ministry. It also seeks to strengthen Israel's National Security Council, now a secondary instrument of the prime minister's office, and give it authority over interagency intelligence assessments and preparations for Cabinet sessions. Such recommendations were made, and rejected, in the past. But the fallout from the Winograd report may be unique enough to force true reform, which if implemented could motivate Israelis to consider peaceful options before rushing to the battlefield. Feeling vulnerable, rather than invincible, may be the greater source of security in the long run.

Shares