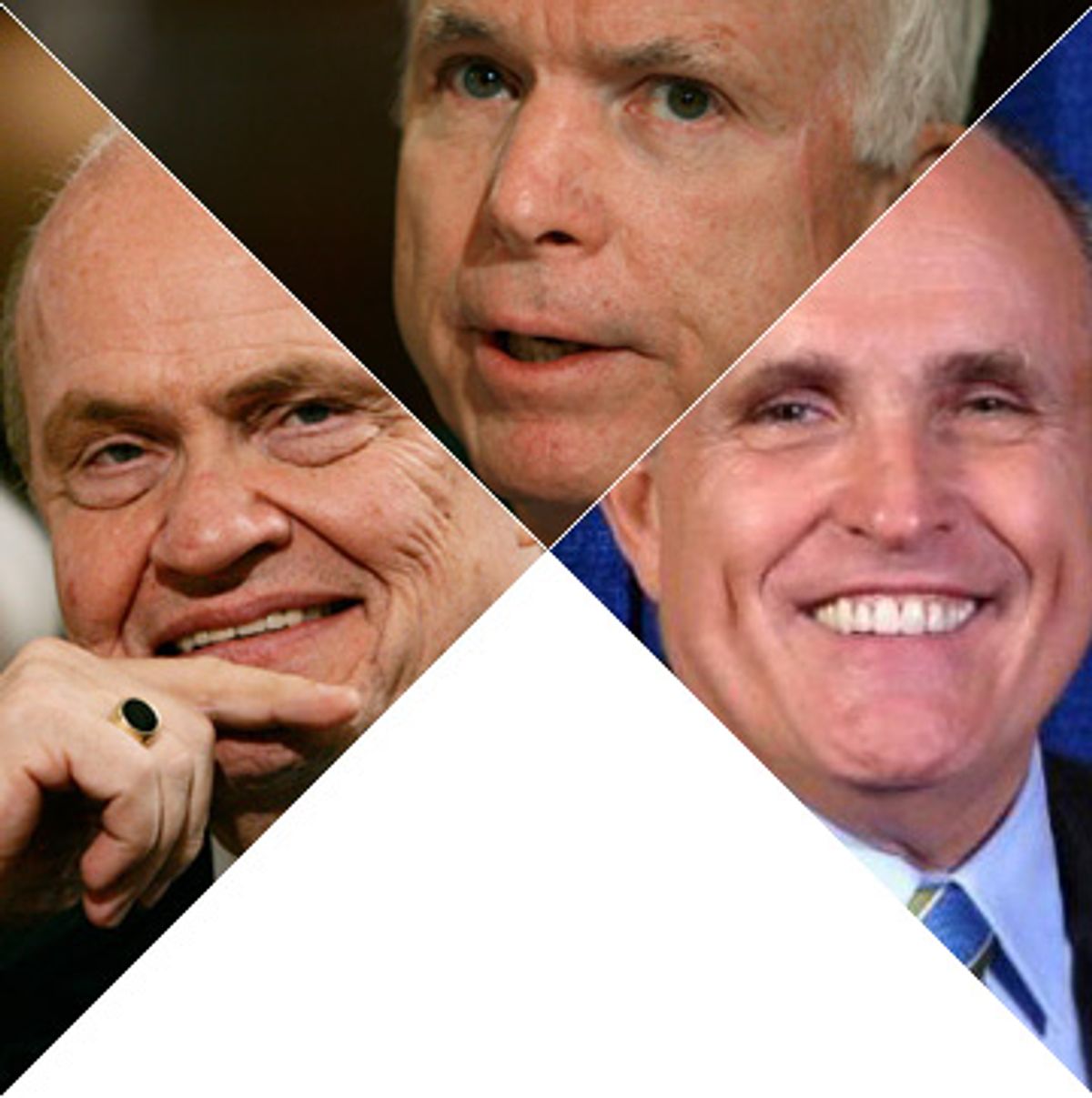

The three leading Republican presidential contenders in most recent national polls share a surprising personal characteristic -- they have all been diagnosed with cancer. With former Sen. Fred Thompson (lymphoma) poised to join Rudy Giuliani (prostate) and John McCain (skin melanoma) in the front ranks of the GOP field, 2008 is shaping up as the "Living With Cancer" election.

While Thompson, still feigning a coy uncertainty about his presidential ambitions, will not be onstage with McCain and Giuliani Thursday night at the Reagan Library for the first Republican debate, Kansas Sen. Sam Brownback will be. Brownback, a long-shot conservative who had two surgeries for melanoma in the mid-1990s, talks freely on the campaign trail about "the beauty of what cancer did for me" in bringing him closer to his family and God.

None of the Republican candidates have faced the stark diagnosis of incurable, but treatable, cancer like Elizabeth Edwards, wife of Democratic contender John Edwards, and presidential spokesman Tony Snow, who is about to start chemotherapy to try to induce remission. And Bob Dole and John Kerry were each nominated for president after they had cancer surgery to remove their prostates. But never before in history have so many serious White House contenders had regular checkups with their oncologists. As Snow, who returned to the White House briefing room this week, told reporters, "Now, I know the first reaction of people when they hear the word 'cancer' is uh-oh. But we live in kind of a different medical situation than we used to."

Thompson, whose stature has grown since he left the Senate through a major acting role on "Law and Order," publicly revealed his cancer in a Fox News interview last month -- and stressed that it was in remission. When asked if there was cure, Thompson said, "I don't know if a 'cure' is ever the operative word when you're talking about cancer, frankly."

Both Giuliani and McCain refer to their cancers in the past tense. The former New York mayor, who was treated with radiation, boasted in a recent television interview, "I'm cancer-free, I have been for six years. I'm extremely healthy and energetic.'' McCain sounded a similar refrain when asked about his skin cancer on "Good Morning America": "Other forms of cancer are much more difficult and complicated. I just get regular checkups and I've been fine for eight years now."

Presidential campaigns often bring onto center stage social trends in the society that have little to do with the policy issues being debated by the candidates. The 1956 election -- even though it took place against the Cold War backdrop of the Hungarian Revolution and the Suez crisis -- was also about Dwight Eisenhower running for a second term after surviving a heart attack. While no political consultant planned it like this, the 2008 campaign mirrors the electorate's evolving understanding of a disease that once was only discussed in hushed and fearful tones.

"I think the American people are getting used to the fact that you can live with cancer like you can live with something like diabetes," said Mark Corallo, who is advising Thompson. National surveys bear this out. A Fox News/Opinion Dynamics poll last month asked voters if Thompson's announcement that he had "a non-life threatening form of cancer" would discourage them from voting for him. Only 11 percent said that it would, about the same number as admitted they were troubled by Kerry's prostate-cancer operation four years ago. Interestingly, more voters (18 percent) in the Fox News survey said they were concerned about the 70-year-old McCain's age.

What appears to be happening is that medical advances in cancer treatment are removing much of the stigma from the disease. As Humphrey Taylor, the chairman of the Harris Poll, put it, "Medically, cancer has gone from a fatal disease to something that is curable -- or something that you could live with for many years and die of something else." In presidential-election terms, Taylor said, "as long as candidates look vigorous and act vigorous, I don't think cancer will be a problem."

Only a minority of voters live blissfully free of direct involvement with cancer. An Opinion Research Corp. poll last year found that 54 percent of Americans said that they or a family member had "suffered" from cancer. Another 16 percent (for 70 percent total) said that a close friend had been diagnosed with cancer. It would be an exaggeration to claim that the nation is in the midst of a cancer-awareness revolution, but certainly the old verities are in the midst of radical revision.

"More cancers are being detected earlier," Harold Varmus, president of the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, said in an e-mail. "More people have a history of cancer -- and are considered living with cancer -- than ever before. There are over 11 million of them, most of them in older age groups and many without current evidence of the disease. Also, cancer is spoken about with greater openness: We are likely to say publicly that we've been through it."

Varmus suggested that perhaps the most relevant aspect in the context of a presidential race are those "situations in which the side effects of cancer treatment or symptoms of cancer are likely to impair performance." As far as we know, no current presidential contender fits into this category. But since, in theory, any candidate can be discovered to have cancer at any time, Varmus said that the clearest distinction might be between "those who have active disease and those who do not -- whether or not they have been diagnosed and treated in the past."

Presidential candidates relinquish their privacy in many ways by choosing to run, but one of the most important is the tradition of releasing medical records so that the press and public can make informed judgments about their health and their ability to withstand the rigors of the Oval Office. In short, a history of cancer should not be an obstacle to serving as president, but a history of lack of candor about cancer should be.

A presidential campaign is too often treated as a life-or-death proposition. But in a season in which so many candidates and their families have been touched by cancer, perhaps the time is ripe for a new sense of proportion in our politics. Living with cancer does not necessarily bring wisdom, but it should, at least, encourage tolerance rather than a continuation of our current to-the-jugular partisanship.

Shares