In an essay about the 1958 travel guide "Say It in Yiddish" in Civilization magazine, Michael Chabon contemplated a country where "I'd do well to have a copy of 'Say It in Yiddish' in my pocket." Of course, not only had Chabon not found such a place but, he pointed out, "I don't believe anyone has."

Chabon, it seems, couldn't get this phantom Yiddish-speaking nation out of his head, and now he's gone and created the place himself. Welcome to Sitka, Alaska, the setting for his new novel, "The Yiddish Policemen's Union," where the only "American" spoken is swear words. In this imaginary world without Israel, Sitka plays temporary home to Big Macher department stores, a thriving Chassid mafia, and some 3 million very cold Jews.

If less epic than "The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay," for which Chabon won the Pulitzer in 2001, "The Yiddish Policemen's Union" is no less ambitious. In addition to being a Chandleresque murder mystery, it deals with the Messiah, a secretive cabal not unlike the apocryphal Elders of Zion, Jewish-American relations and the perennial question of what it means to be a Jew. If all this sounds like too much, you may be right. But, as is the case in most of Chabon's novels, it is his characters, at once absurd and entirely familiar, that hold the story together. Here we have Meyer Landsman, a secular policeman with a bad case of the shakes, whose favorite daydream is to imagine the many ways he could take his own life; and his half-Indian partner Berko Shemets, a hammer-wielding gumshoe more devout than most of Sitka's Yids. "These are weird times to be a Jew" is the refrain of those in Sitka, and so, one feels, has it always been. Coming from Chabon, it is perhaps unsurprising that a fiction set in a fantastical place, told in a dying language, poses some of the most poignant, difficult questions about the Jewish homeland.

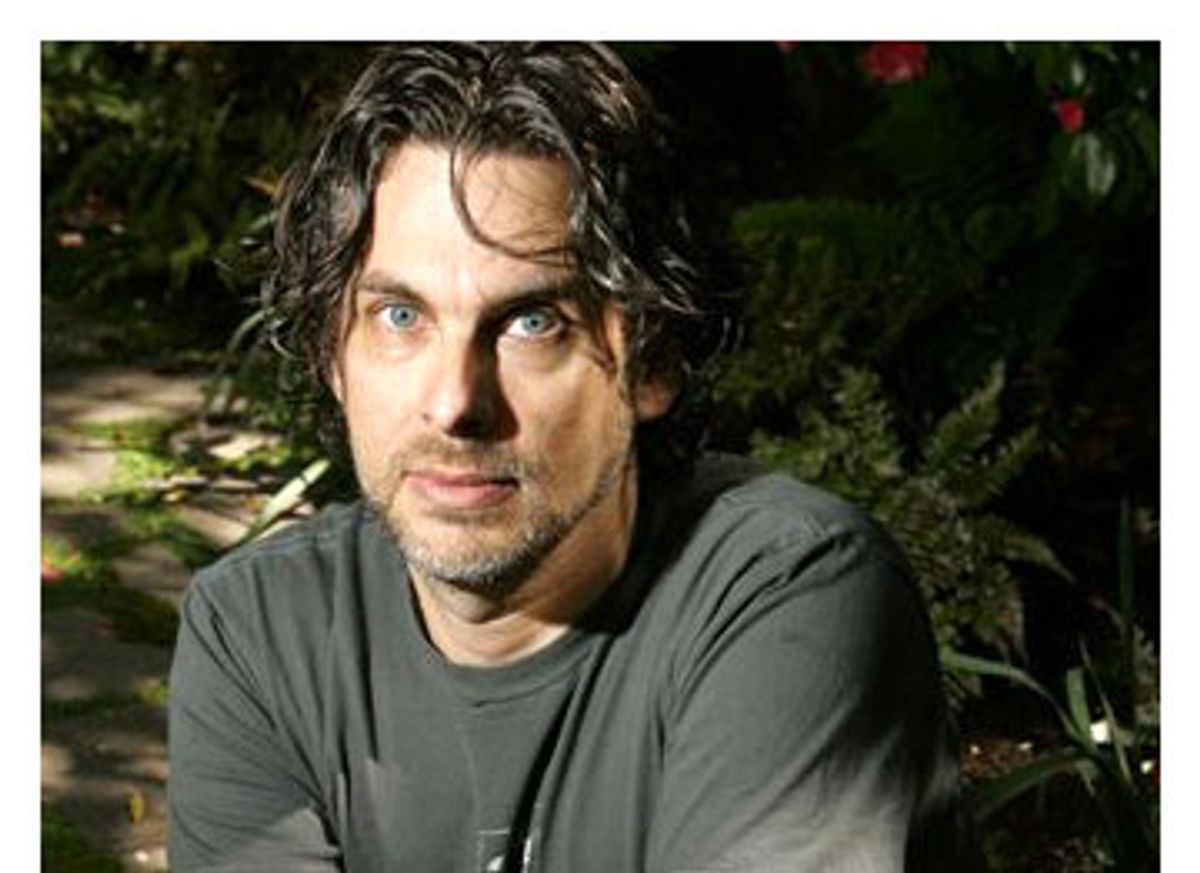

Salon caught up with Chabon in New York, a place he still fancies as "'Kavalier and Clay' land," where he spoke about why he likes being called anti-Semitic, what it's like being married to another writer, and why he's obsessed with Barack Obama.

The book is set in Sitka, Alaska, which you have made the temporary home to Yiddish-speaking Jews, in a world where Israel doesn't exist. Why make it a detective story on top of all that?

I wanted to find a way, narratively, to range as freely as I could across the whole of this place and every level of this society. I just kind of felt it as an intuitive leap that a detective, a policeman with a badge, would be able to go everywhere, see everything. He would be informed, he would understand how the world operates -- the written and the unwritten rules.

Some moment around the time that I was conceiving of this book I reread Isaac Babel's short stories and I just felt like there was a stylistic link there between Babel and [Raymond] Chandler. Isaac Babel was a hard-boiled writer; he was tough and deliberately so. He almost wore his hardness as a badge of honor in a way that I felt like I recognized also from Chandler and [Dashiell] Hammett. And he was writing around the same time as Hammett and Hemingway; it just didn't feel like a totally ridiculous comparison to make.

I was also reading a lot of Ross Macdonald while I was writing this and I noticed not only did he have short chapters but he would sometimes break a scene right in the middle into two chapters, right on a line of dialogue.

Which you do throughout the book, and which is oddly fitting with the Yiddish dialect -- the interrupting, and the economy of speech. What is your own relationship with the language? Did your grandparents speak Yiddish?

Yes, I grew up hearing it. My grandparents both spoke Yiddish on my mother's side and their siblings spoke it as well, my grandmother's siblings, and my great-aunt got the Daily Forward in Yiddish. I heard the language all the time. I wasn't intended to understand it and typically they would use it when they didn't want us to know what they were saying. It was like Navajo Indian code talkers. [Laughs] So there was always this air of mystery and secrecy about the language.

You are perhaps the last generation to be familiar with the language.

I think the living native speakers of Yiddish who aren't ultra-Orthodox, who use the language every day, are an ever dwindling number. I mean, it already had that quality for me of something a couple generations removed and I was sort of transfixed by the survival of it. Like when I was a kid they still had pneumatic delivery in department stores and pneumatic tubes that would deliver mail and things like that. They're these almost antique but fully functioning systems that are still in use in little pockets of the world here and there, and when you encounter them you're always struck by how well they function and you wonder what happened to them and why we don't still use them. For me, Yiddish had a little of that quality.

You get at this idea, the otherworldliness of Yiddish, in the original essay you wrote about "Say It in Yiddish." You wonder where this fantastic or magical place is where one would speak Yiddish. Now you have your place.

Yes. Sitka is a kind of fantasy land in a way. When I was a kid, what it meant to write books was to make maps and create chronologies and I was really into "Lord of the Rings," for example; that was all about chronologies and charts and maps, and this novel is sort of my Middle-earth.

That's a good way of looking at it -- the Verbover Chassids as hobbits. Another analogy that's been made is to "The Plot Against America," an example of another Jewish-American writer -- and we can talk about that title in a second -- writing a counterfactual story of the Jews. Is there something about Jews and Jewishness that makes the "what if" story so appealing?

I don't know. Certainly it's hard to think of something that would be more focused simultaneously on the past and on the future than Judaism, because Judaism is all about history and what happened to us and how we got where we are. The patterns of our history and the crucial moments -- the destruction of the temple, the expulsion from Spain, Kristallnacht, these key moments, these dates that both seem to change everything and yet merely were repeating, in some way, the last time.

And yet at the same time Judaism, in its truest form, is very focused on the future, on the coming of the Messiah, on the redemption of the world. To have that sort of simultaneous sense of looking backward and looking forward -- I think it does definitely lend itself to the kind of speculative, hypothetical thinking of the counterfactual novel. You're looking at history ... and asking, "Where are the moments where things changed, where history forked and it could have gone this way?"

And even the whole "Next year in Jerusalem" refrain.

Absolutely. I mean, in a way the Messiah story is kind of the ultimate science fiction; it's kind of a prediction of this brave new world that is always yet to come.

When the novel begins the Jews of Sitka are two months away from Reversion -- when the land will return to the Alaskans. This is the perennial fear of the Jews, isn't it? Why was the Reversion necessary to "The Yiddish Policemen's Union," which is otherwise a provincial detective story?

This story, I think, is about the status quo of the Jews, who are always on the verge of being thrown out, of being shown the door. I think that has been the Jewish story in every era there have been Jews, going back to the very beginning, certainly going back to Moses and the coming of Joseph to Egypt and the expulsion and the flight from Egypt. That's the Jewish story and I guess what I came to realize in writing the novel is that it's still the Jewish story. We may look at Israel, we may look at the incredibly secure-seeming position of the Jews in America today and think, "Well here we are. This is now, that was then, this is the end of Jewish history. It's been fulfilled -- we have Israel, that's our homeland."

I didn't set out to do this when I started the book but what I ended up contending with is, because of the absence of Israel in the world of my book, the Jews are in that classic typical position of being guests, wherever they happen to be. That was the inevitable result of taking Israel out of the picture. And then having taken Israel out of the picture I felt I really had to confront head on the very real, omnipresent possibility of expulsion -- of Reversion, as it's called in this book. And I realized having written the book, it's still the status quo for us today. We may feel secure, with Israel having the fifth-largest military force in the world. But I guess that sense of fragility, of always being on the verge of being expelled -- at best -- is something I think we're still living with even if we prefer not to think about it.

So much of the new book is about Jewish identity and how Jews identify in relation to place. Is "Jewish-American" writer a title you embrace?

I guess in a way it's a title I've sought and I'm proud to have, and in fact this little bit of controversy that's already been awakened by this book and the thing that was in the New York Post last weekend, if anything it makes me feel all the more secure in my credentials as a Jewish-American writer. I don't think you've arrived as a Jewish-American writer until you've been attacked for being self-hating and for airing our dirty laundry and making a chanda for the goyim.

Let's talk about this claim of anti-Semitism. In the book there's this cabal of powerful, secretive Jews and that obviously raises issues of stereotype.

Right. I mean, I don't know, it was hard to interpret that Post thing. The claim was made that the most ugly thing in the book is that Jews are being depicted as being willing to massacre other Jews, which doesn't happen in the book.

Indians are killed by Jews.

Right, exactly. I think ultimately the charge is always if you portray Jews as divided then you are playing into the hands of the enemies of the Jews. Or you are giving aid and comfort to the enemy. That is as bogus an argument for Jews to be making as it is for Republicans to be making about Democrats who are opposed to the war in Iraq.

When I heard about that Post thing last weekend I called my mom and she went and checked it out and you know her response was, "Congratulations, you're in the club now." It made me think of Philip Roth in "Portnoy's Complaint." You know, Roth is one of her favorite writers and she remembers very clearly all the outrage he has elicited at many times in his career starting with "Goodbye Columbus."

You brought up Republicans so I want to ask you about your own recent political activism. You and your wife [novelist Ayelet Waldman] are raising money for Barack Obama, right?

Oh. Yeah, yeah. How did you know?

It was posted on gawker .

It was?! What was posted? What we sent out in the e-mail?

I guess you have the Web site -- mybarack -- and then your picture. And "help us raise $25,000 dollars for Barack Obama."

Oh my god, that's outrageous. [Laughing] Wow. We sent out an e-mail to pretty much everybody we had an e-mail address for who we felt like we had a right to pull on their sleeve. You can create this page through the Obama campaign where you solicit donations and people just click on the link and they can donate any small amount. It seemed like a really great way to raise money for Barack Obama, of whom I'm just completely enamored. I've been voting since 1984 and in every election I've always had to hold my nose, or at best I was all right with the idea of whoever it was I was voting for. I mean I've never been completely certain, completely passionate about a candidate in my entire life as a voter until Barack Obama and it's such a strange, exciting feeling.

What is it about him that you like so much?

In addition to that he's of my generation, he's the same age I am and I feel like he speaks my language in some way --

Not Yiddish?

No, not Yiddish, at least as far as I know. For one thing the guy can write. He's a really good writer and that means a lot to me and is not true of almost anyone else who's ever run for office since I've been voting. I know that might seem silly, but that means something to me. But it's not just that he can write, it's that his writing, especially when he writes about America and American history, displays this sense of complete ambivalence. Of being fully conscious of both what's great and what's terrible about America and American history. The ills, the evils, the massacres, the injustices that have been done, and at the same time a sense of pride and faith and optimism that's coupled with a totally clear-eyed sense of the grimness that's there as well.

Changing tracks now, I want to ask how you feel when your wife writes about you, sometimes quite intimately?

Payback is a bitch. I've written about my parents, I've written about my ex-wife, my in-laws, my kids. I've made use both in fiction and in nonfiction of things that have happened to me. I've felt that I've had to do it and if I was going to be hurting somebody by what I was writing then I felt bad about that, but I also felt that I couldn't help it, I needed to write what I needed to write.

But her writing hasn't been negative or critical of you, quite the opposite.

No it hasn't been, but it's just a question of doing it at all. I wrote something about my dad a long time ago, about him giving me some old baseball cards, that to me I felt was a very loving thank you for his gift of these old baseball cards. He took it badly and it bothered him and I'm still not really sure why. It was a long time ago, we both got over it, but you never know. He thought I was making fun of him, I think. You never know how people are going to take things; you do it anyway, whether you think it's going to go over well or not. Sometimes the things you think are going to go over well don't. You can't worry about that shit before you start writing. That's the trouble with having a writer in the family. They're vipers.

Before you go, can you tell me if the movie version of "Kavalier and Clay" is ever going to come out?

It had supposedly been green-lighted and key crew members were already on their way to London where shooting was to take place and it just all fell apart over a question of studio financing.

"Policemen's Union" might actually work better as a film than "Kavalier and Clay," which is so huge and takes place across time, and media, and distance...

I agree. I think because it has that detective novel structure, it would work in a film. Although the idea of trying to get a studio to pay for a movie that's set in an imaginary Yiddish-speaking Alaskan-Jewish territory...

Shares