Former Sen. Fred Thompson is a big man, broad shouldered, maybe 6 feet 4 inches, with hands like Sasquatch and a bald head like a bowling ball. When he acts on television or in the movies, he gets picked for fearless authoritarian roles that fit his large and in-charge stature. He's "Law and Order's" District Attorney Arthur Branch. He's "Die Hard 2: Die Harder's" head of air traffic control. He's "The Hunt For Red October's" Rear Adm. Josh Painter, who quips to Alec Baldwin in a low Tennessee drawl, "Russians don't take a dump, son, without a plan."

So it was odd Friday night to see this lawyer turned actor turned lobbyist turned senator turned actor turned probable presidential candidate flee down a Southern California hotel corridor to escape the questions of a limping New York Times reporter. The scribe had been waiting for about 20 minutes, chain-smoking while Thompson gave an interview in a nearby room to Fox News. After finishing a second interview with a local newspaper reporter, Thompson tried to make an escape out a back door.

The evasive action seemed out of character. But then Thompson is still reading scripts and mulling the biggest role of his life. He hasn't yet accepted the part of presidential candidate. To date, his handlers have been careful to feed him mostly to friendly conservative media outlets, who are happy to fan the Thompson mystique without any jarring questions. In these interviews, he alternates between his country-fried Ronald Reagan act and traitor-baiting the Democrats. "They are taking extremist positions and doing extremist things," he recently told Fox's Sean Hannity. "They are as near to investing in the defeat of their country as anything I have ever seen." He showed off his Cuban cigars to a writer for the Weekly Standard, and began signing his name to columns in the National Review on topics like gun ownership and the need for Western civilization "to get a little backbone."

This is all political throat-clearing, not presidential campaigning. But it appears to be having an effect. In April, five national polls placed him in the top three of the Republican primary candidates with New York Mayor Rudy Giuliani and Arizona Sen. John McCain. "What I'm seeing is something I have never seen before in 21 years," says Bob Davis, the head of the Tennessee Republican Party and a close Thompson advisor. "Here's a guy who has not spent one dollar, and he is showing up in some places second in these national polls, and he is winning some of these straw polls." Roughly one in three Republicans still say they are dissatisfied with their presidential choices, compared to one in six Democrats. Thompson seems to think he might be a big enough man to fill that void.

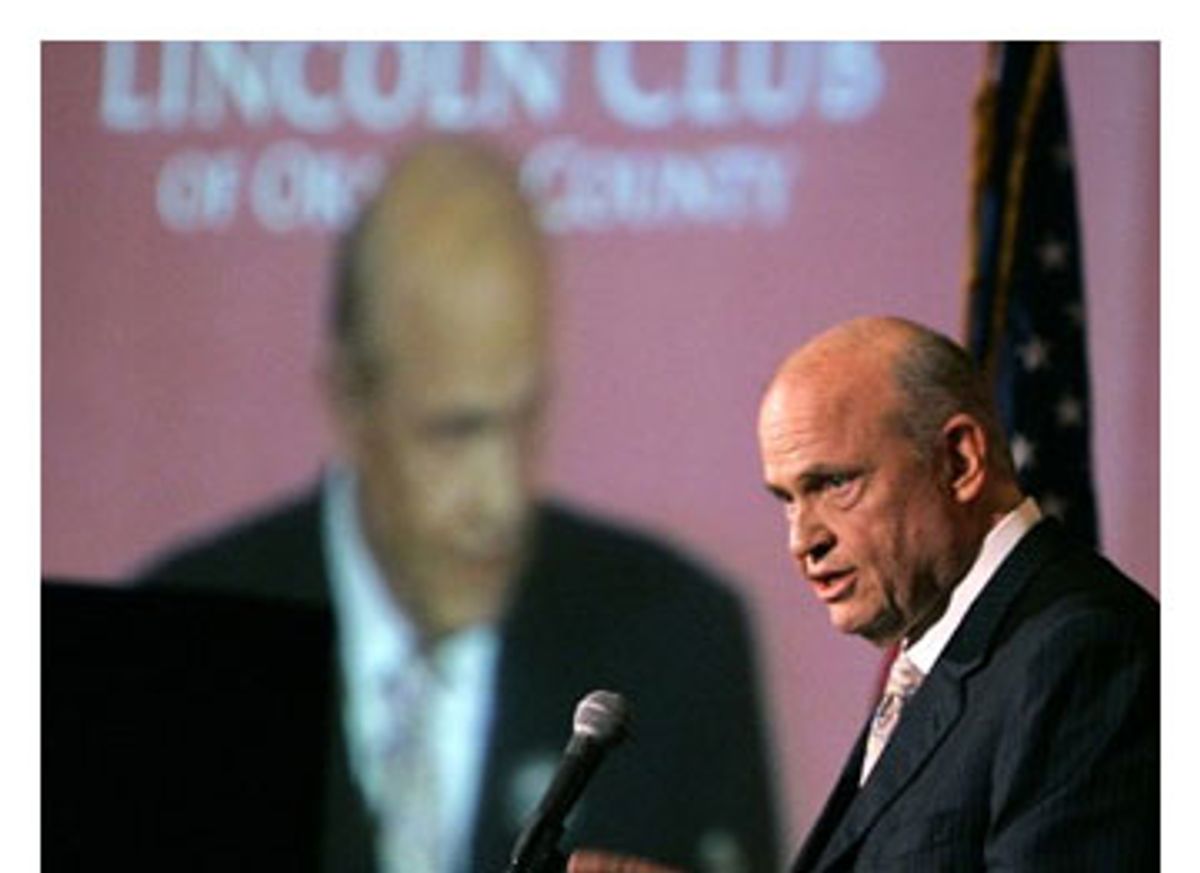

"You ever wonder why when our problems seem to be getting larger, so many of our politicians seem to be getting smaller," said Thompson, looming over the podium at the Lincoln Club of Orange County's annual dinner on Friday. He had come to make a sort of inaugural policy speech for his undeclared campaign, attracting about 50 credentialed media types. The setting was the Balboa Bay Club, a redoubt of the wealthy and white on Southern California's yacht-lined coast. O.C. Republicans have a storied history as kingmakers. Their money helped launch Richard Nixon's presidential comeback in 1968 and Ronald Reagan's gubernatorial campaign in 1966. The Lincoln Club's endorsement effectively cleared the field of other candidates for the current Governator Arnold Schwarzenegger.

But Thompson's address to the crowd was decidedly low-key, with no mention of inflammatory social issues and only broad hints at a policy framework. He said he would keep taxes low and fix Social Security by telling "Mom and Dad and Grandma and Granddad" to make sacrifices for their offspring. He said the borders must be sealed to solve immigration and American troops must stay in Iraq "as long as we have any chance there." He warned of mushroom clouds in American cities and military buildups in Russia and China. "Even though we won't be going around in the woods trying to find any bears to kill, sometimes the bear comes to visit you," he said, in the unmistakable voice of Arthur Branch, Adm. Painter and that guy from the flight control tower in "Die Hard."

But the substance of his speech wasn't policy. It was his easy style and stature, his obvious charisma. He spoke in a conversational manner, often with one hand in his pocket, barely looking at his notes. He criticized the "professional politician," and compared the Cold War to a rodeo. Thompson's defining feature as a politician is that he comes across like the parts he plays in movies. "Fred, he is what he appears to be," explained a prominent Tennessee Democrat. "I don't think he ever comes out of character." This description, which came from a political foe, explains a careful trick of Thompson's career. Either he is never acting, and just plays himself in movies and television, or he is always acting. There is only one character there.

In interviews, Thompson describes himself as an actor who doesn't have to act. "That's the strength of Ronald Reagan," he told the Orange County Register, in one of the two interviews allowed after the event Friday. "He was almost the anti-actor. People say he was the 'great communicator' because of his acting background. Just the opposite. He was the great communicator because he believed in what he was saying and that came across as genuine and authentic. And he stood by those beliefs. The camera doesn't lie."

Of course, the camera does lie. Hollywood is built on the premise that it lies very well. But as a political maxim, such assertions have great staying power. Whether it was Reagan in 1980, Bill Clinton in 1992, or George W. Bush in 2000, the candidate who appeared most down-home and authentic on camera, despite other evidence to the contrary, won the election. There's little doubt that Thompson's side job as an actor will aid him on the trail. "He's been a law-and-order type of guy," says Davis, his friend and advisor.

Born in Alabama, Thompson came of age in Tennessee, the son of a used-car dealer. He married young, at the age of 17, and graduated from law school at Vanderbilt. His work for Sen. Howard Baker led him to Washington, where he served as the minority counsel on the Senate Watergate Committee, famously asking the question on live television that led to the discovery of Nixon's listening devices at the White House. Like his boss Baker, he earned a reputation as a good-government investigator, more interested in ferreting out corruption than partisan loyalty. After returning to Tennessee, where he became a private attorney, he helped uncover a parole-buying scandal. That earned him his first movie role -- in a film about the scandal in which he played himself. He then worked for more than a decade as a lawyer and Washington lobbyist, representing companies like General Electric.

In 1994 he decided to run for Al Gore's vacated Senate seat. But rather than run on his Washington experience, he presented himself as a local boy, with blue jeans and a red pickup truck, who opposed the Washington establishment. The act worked. Upon his return to Washington, he legislated for eight years as a consistently conservative Republican, albeit with a reformist streak when it came to government inefficiency and signs that he could still ignore party labels when it counted. In 1997, Thompson led a Senate investigation into potentially illegal foreign contributions to the 1996 Clinton campaign, an inquiry that he expanded to include prominent Republicans like Haley Barbour, who is now the governor of Mississippi.

After co-chairing McCain's failed 2000 presidential campaign, Thompson announced he planned to run for reelection in 2002. But then his 38-year-old daughter, Elizabeth Panici, died suddenly of a reportedly accidental drug overdose, which left high levels of an addictive painkiller in her bloodstream. Weeks later, Thompson decided against seeking another term and chastised the press for snooping into his family's affairs. "I simply do not have the heart for another six-year term," Thompson told the Tennessean newspaper in Nashville.

Now that he is heading toward a White House run, with a likely decision coming in the next couple of months, Thompson has opened himself up to a number of questions about his past, which has never before been scrutinized in detail. If he joins the race, he will be the least-examined candidate in the top tier of the Republican field. Opposition researchers have already sprung into action. "There are people down here in Tennessee right now," said Davis. "There are people looking over at different places where we've got papers. But so be it." Thompson recently disclosed that he has a treatable form of lymphoma that is in remission. At a meeting with House Republicans, Thompson reportedly admitted to an eventful dating life after his divorce in 1985. "I chased a lot of women," he said. "And a lot of women chased me." In 2002, shortly after dropping out of politics, he married his second wife, Jeri, a Tennessee political consultant 25 years his junior. The 64-year-old Thompson now has two children under 5.

But the big questions of a potential Thompson candidacy have yet to be asked and answered. Why reenter politics now, just five years after saying he had lost his passion for politics? How will he distinguish himself in the crowded Republican field? Will he run as a uniter, as he claimed at the Balboa Club, or as a divider, who accuses Democrats of "investing in defeat," as he did on Fox News? What does he think of the current president's failures? How far to the right is he willing to shift to get votes in the primary? Is there substance there, or is he merely playing another part?

At the moment, the larger-than-life Thompson is walking away from those big questions. But his strategy cannot last for long, as the New York Times reporter Marc Santora made clear on Friday, chasing Thompson down one long hallway, and then another, before Thompson and his entourage made it into the Balboa Club lobby and promptly disappeared. Santora was nursing a foot injury, a fact that allowed Thompson to escape. But further scrutiny still trails him. Unless he drops out as a presidential candidate, the actor will soon have to prove that he is more than just an act.

Shares