Kevin Smith and his unit have just finished an unsuccessful search for snipers inside a house in Fallujah and are headed back to their base. Smith is behind the wheel of a Humvee, the seat beneath him vibrating from the familiar roaring engine. He makes a left turn and suddenly there is an ear-splitting boom, an explosion right behind him that rocks the vehicle. The sky goes dark and smoky, and Smith senses the piercing pain of shrapnel in his neck and hands. The Humvee's radio crackles with voices asking for information, as his mind races. Will there be more explosions or a hail of bullets from unseen snipers? Are his fellow soldiers hurt? Time seems at once to speed up and slow to a crawl.

Then, just as suddenly, a voice cuts into the nightmare: "What are you thinking right now?"

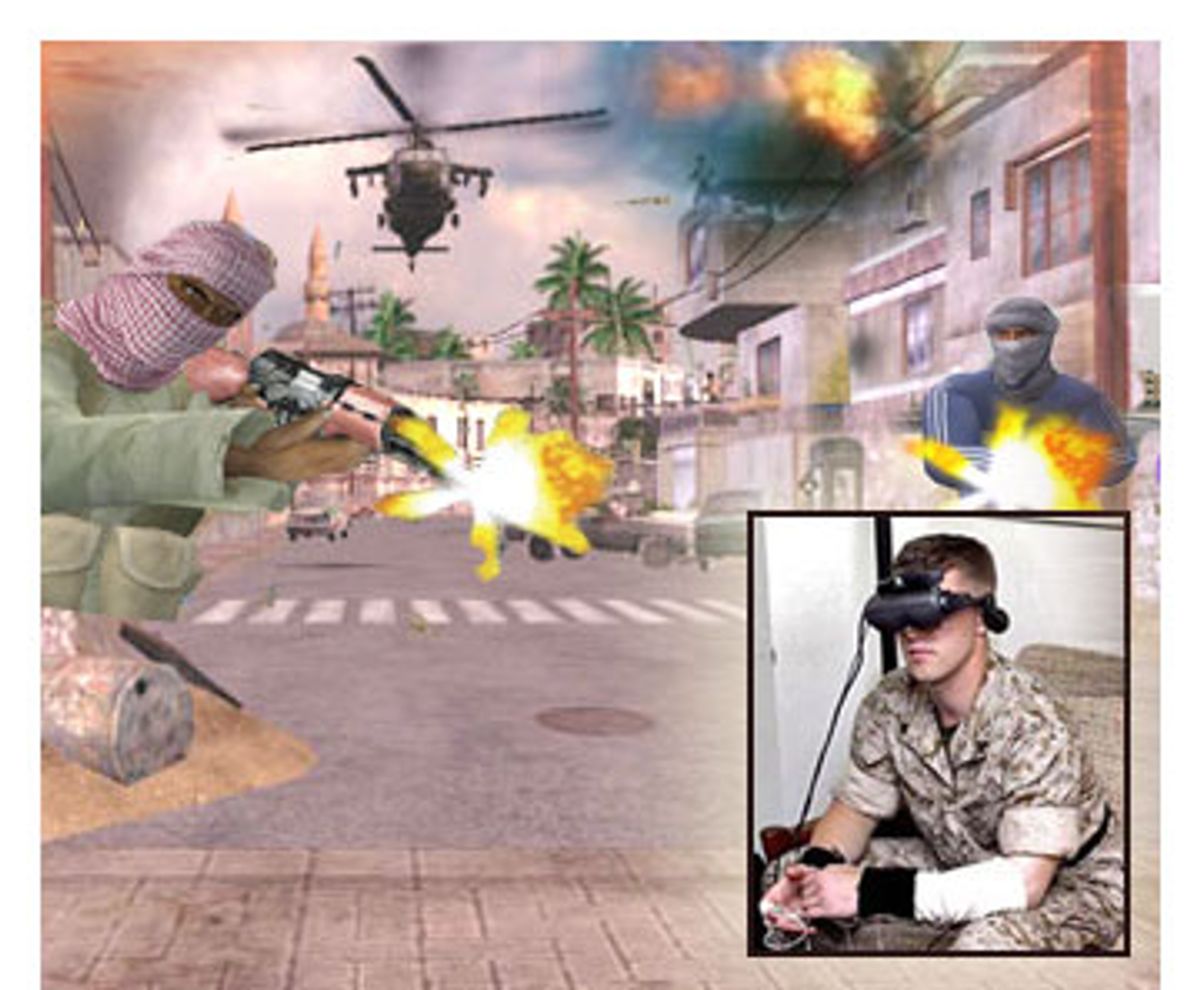

It is the voice of Maryrose Gerardi, a psychologist at the Emory University School of Medicine and Smith's guide through the world of "Virtual Iraq." Smith isn't actually in Fallujah, where he served as an Army infantry scout in 2004; it is April 2007, and he is in Gerardi's office, wearing a sophisticated headset and sitting in a chair on a vibrating platform. Smith is one of a handful of Iraq veterans involved in the trial of a cutting-edge therapy that uses a high-tech virtual reality system to treat war veterans afflicted by post-traumatic stress disorder.

Smith, Gerardi and the designers of the virtual reality system say the experimental treatment has had such positive results that it may prove to be the most significant advance in years for the treatment of PTSD -- a problem of growing scope among veterans returning from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. The treatment's healing power derives from repeated exposure, using vivid simulation, to a veteran's most traumatic memories of war.

For years, experts have considered exposure therapy, also known as talk therapy, to be the most effective treatment for PTSD: Doctors help their patients recall and confront troubling experiences, until the patients are habituated enough to control their emotional response. Virtual reality therapy is like exposure therapy on steroids. It plunges the patient into a direct sensory experience of past events, potentially accelerating the coping process.

As the veteran begins to recall an incident, a clinician introduces elements into the experience: A car bomb suddenly explodes, a building catches fire, insurgent snipers unleash a spray of bullets. "Virtual Iraq" resembles a video game, but it is also a convincing portrayal of the war zone, according to Smith. "It was like I was really sitting in the Humvee," he says. "From behind the steering wheel, everything looked like what it really looked like there. The streets, driving down the road, the desert landscape, the mosques, the people, were realistic enough." Other simulated sights and sounds include wind, a Muslim call to prayer, babies crying, footsteps, helicopters, rockets and gunfire. The veteran walks, stands or sits on the platform, which has a range of motion. The system, still under development, is also starting to incorporate smells, including gasoline, rotting trash, cordite, diesel fuel, spices and gunpowder.

Smith, whose real name has been withheld, recently finished participating in a five-week trial at Emory. He is one of eight Iraq veterans who have undergone the experimental treatment there; a handful of others have participated in virtual reality studies at military bases in California and Hawaii. Smith is the first Iraq veteran who has completed the treatment to speak about it publicly. He agreed to talk with Salon about his experiences both in Iraq and in the virtual reality treatment if his identity was kept private.

Smith was a 20-year-old college student living with his parents in Georgia when he joined the Army. He was deployed to Iraq in January 2004. Serving as an infantry scout meant Smith was either driving a Humvee or gunning -- standing half-exposed in the turret, manning a .50-caliber machine gun. His days were a blur of firefights, of killing and the fear of being killed. He got little sleep, he says, often staying up for days during a mission, and returning to base for some sleep only to be awakened a few hours later for another mission. As Iraq spiraled into deeper chaos, he was constantly on guard against snipers, suicide bombers and roadside explosives.

"How do you feel right now?" Gerardi asks during the pause in the simulated ambush. Some soldiers become so upset or anxious that the therapist may have to shut off the program. "I'm OK," Smith replies. In the beginning, Smith says the explosions and the sound of the radio going off made his heart race and his stress level quickly rise. "I started to get nervous and couldn't really talk. I was mumbling but I didn't even realize it at the time. Dr. Gerardi told me she couldn't hear me."

She asks him to rate his anxiety level on a scale of 1 to 100, a regular way of monitoring his response. Then he's back behind the wheel of the Humvee, doing it all over again.

The goal, according to Gerardi, is to get a veteran to grapple with a selected memory at least twice if not three times in each one-hour virtual reality session. "With every repetition we get more details, and the memory becomes a more complete story. We want a narrative that makes sense and has all the sights and sounds," she says. "But most important are the feelings that were happening at the time. In a survival situation you don't have time to feel terror or grief about what is happening at that moment."

That tends to come weeks, or even months, later. When Smith got back home to the United States in December 2004, he was plagued with nightmares, sleeplessness, irritability, jumpiness and depression. Terrifying thoughts of Iraq could enter his mind at any moment. Driving was difficult. "Bridges startled me," he says. "Leaves blowing over the car. I was always looking for things on the side of the road."

After several unsuccessful attempts to get effective treatment, Smith entered the virtual reality trial, and his fears finally began to diminish. "Every time I told the story, the less it bothered me," Smith says. "For a long while I felt like I had done something wrong in Fallujah. They teach you in basic training that if you get shot, you did something wrong. They want you to be motivated. They tell you that if you die, it's your fault. It was my Humvee and I was in control of it. I felt it was my fault."

"He was very courageous," says Gerardi. "He had some very difficult stuff to think about during the treatment. It was exhausting for him. It's a very hard thing to do."

Yet, despite Smith's progress, some memories from Iraq are still too gruesome for him to confront.

When his unit first arrived in early 2004, Smith says Baghdad wasn't terribly violent, and although there were occasional ambushes and roadside bomb explosions, it felt manageable. In late spring, he killed a person for the first time. It was then that he also first saw a dismembered body. "It was pretty traumatic," says Smith. "Then things got worse. There was a lot of shooting, a lot of killing."

Some of the experiences he survived "are too much for me," he says. "I don't want to relive them again."

But it's also clear that Smith is determined to win this protracted war within himself. He says that if his virtual reality treatment had continued for longer than five weeks -- researchers are conducting 10-week trials at the military facilities in California and Hawaii -- he would have attempted to confront other troubling memories. "Definitely certain scenes get me upset more than others," he says. "One is when we shot up some insurgents in Fallujah, and one of the guys we shot didn't die. He was pulling his brains out of his head. And I stood there and laughed at him. It's just that we saw so many dead people. But afterwards, I felt like, holy shit, I just saw this and I laughed at it. I would think back on it, and it really disturbed me. Then it just gets in your dreams and you think about it every day."

The cliché "war is hell" became true for Smith during one combat operation he refers to only as "the cemetery."

In August 2004 his unit was sent to help quell an uprising in Najaf Cemetery in the city of the same name. One of the world's largest graveyards, it is sacred to Shiite Muslims; millions are buried in its terrain, whose focal point is the shrine of Imam Ali, son-in-law of the prophet Muhammad. "It's like no other cemetery you've ever seen," says Smith, still struggling to discuss it. "The bodies are buried vertically and there are a lot of tombstones, like houses, and the cemetery went on for miles. We were in close combat, you're getting shot at all the time. There were all these underground tunnels and it was August -- like 120 degrees -- and we were running around in these tunnels trying to find people. We were there for two weeks. It was one of the worst experiences of my life."

Smith is one of the lucky ones. Many veterans of the war are suffering from PTSD and going without adequate treatment. In fact, mental health problems are the largest unmet need in veterans' medical care, according to a recent study by Harvard economist Linda Bilmes. And the problem is growing: The Department of Veterans Affairs now estimates as many as 20 percent of those returning from Iraq suffer from PTSD, while a study released in March by the VA and researchers at University of California at San Francisco showed that nearly one-third of all veterans from Iraq and Afghanistan have some type of mental disorder. Yet, veterans must battle a sluggish bureaucracy to get help. A report from the Government Accountability Office released in March said VA officials estimated that follow-up appointments for veterans receiving care for PTSD may be "delayed up to 90 days."

Those who do get access to mental health professionals often receive inadequate treatment, according to veterans and their advocates. Caregivers within the military system often tell veterans afflicted by PTSD that their problems are just "normal readjustment issues," says Joy Ilem, who specializes in mental health issues as the assistant national legislative director of Disabled American Veterans. "These doctors need to be trained to recognize that symptoms that may seem physical in nature are not," she says. "A lot of times there just isn't adequate oversight, because the system is so massive."

For the treatment of PTSD, both the Department of Defense and the VA's clinical practice guidelines recommend exposure therapy, which includes eye movement desensitization and reprocessing, or EMDR, in which patients rapidly move their eyes while re-imagining a traumatic event. But many doctors stick to traditional psychotherapy, which typically doesn't help vets confront traumatic memories. Or they just prescribe medications like sleeping pills, antidepressants and anti-anxiety drugs, and send them home.

Smith found himself on that tortuous path before finally getting effective help. He had gone to see a psychiatrist at Brooke Army Medical Center in Houston, while he was there recovering from his wounds from the Humvee ambush. "I talked to her a couple of times and then left. I think maybe she had seen too much of what I had and shrugged it off," Smith says. "She didn't seem to care much about it. She gave me some methods for coping, some stuff I should do to take my mind off it. But I didn't get any actual treatment."

For a while Smith even thought he might not have PTSD. But the symptoms persisted and got worse. He sought help again, this time closer to home, at a VA center in Georgia, where he returned after his release from the hospital. There he saw six or seven doctors, he says, and wound up with medication -- sleeping pills and antidepressants -- on which he is still dependent. But one doctor at the VA center also directed Smith to Emory's virtual reality trial.

Virtual reality treatment is new for Iraq war vets, but its beginnings go back to 1997, when researchers at Georgia Tech released the first version of a more primitive program, called "Virtual Vietnam." A study in 1998 found that even two decades after that war, symptoms of PTSD in Vietnam veterans were reduced by 34 percent when they were treated using the program. That prompted researchers at the Institute for Creative Technologies at University of Southern California to initiate a project in 2004 to create an even more immersive environment, using the latest technology.

Researchers at USC used the Xbox game "Full Spectrum Warrior" as a starting point, adding virtual elements, different scenery, motion and smell. One of the chief architects of the new system, research scientist and psychologist Albert "Skip" Rizzo, says that for people who haven't been in combat, "Virtual Iraq" may look cartoonish -- but to war veterans, who bring their own memories to the experience, it's anything but a game. "With 'Virtual Vietnam,' we had a rice paddy and a helicopter. That was it. Soldiers would say, 'I was being shot at by guys in the jungle' and, 'I could see the V.C. and there was a water buffalo.' But none of that stuff was there. It was in their memory." With "Virtual Iraq," Rizzo says, the scenery is more complex and the entire experience more sensory, which draws out more details.

There are still some gaps: During the simulated Humvee attack, for example, Smith couldn't look down while wearing the headset and literally see the knuckle on his hand blown off, or all the blood, or his injured comrades. But enveloped by the other sights and sounds, those details came alive again in his memory. "This process isn't just about being exposed and sitting passively," says Rizzo, "but talking about what you went through while you were there. Virtual reality serves as a prompt for that."

Emory's five-year study of the virtual reality treatment, begun this year, is funded by the National Institute of Mental Health and is open to any Iraq war veteran diagnosed with PTSD. It tests the effectiveness of virtual reality therapy in conjunction with a small dose, just prior to the session, of a medication usually used to treat tuberculosis: d-cycloserine. Taken before therapy, d-cycloserine can greatly reduce feelings of fear, researchers have found. But it is a "blind" study; Smith was put into one of three groups, so he doesn't know if he received the d-cycloserine, Xanax (an anti-anxiety medication) or a placebo.

Smith says virtual reality therapy has been the best treatment he's had so far. "I'm not as depressed. Talking to people is much easier. I'm less irritable, and I'm not as scared of the memories," he says. Soon he will start seeing a psychiatrist for weekly exposure therapy sessions. "I think maybe then I'll go over the Najaf memories," he says. And he has since gone back to school and work, studying civil engineering and working part time at a Home Depot.

Initial results from the virtual reality treatment have been striking. "It's still early so I don't want to make grand claims," Rizzo says, "but the results are excellent." Four patients in the San Diego trial have completed treatment, and their last medical assessment indicated they no longer qualified for a diagnosis of PTSD, according to Rizzo. (One person completed treatment in San Diego with no benefit; that case is being examined. Two others started treatment and dropped out before completing it, which Rizzo says reflects the typical dropout rate for most forms of therapy.)

Barbara Rothbaum, director of the Trauma and Anxiety Recovery Program at Emory and the psychologist directing the "Virtual Iraq" study, has been treating PTSD since 1986. "I think this might be a powerful tool," she says. "These guys seem to be doing very well in just five sessions."

A non-military-related study of virtual reality therapy -- being used to treat rescue workers involved in the attack on the World Trade Center -- has also had promising results. JoAnn Difede, director of the Program for Anxiety and Traumatic Stress Studies at the Weill Medical College of Cornell University, recently published early results from the WTC study showing that after 14 weeks of virtual reality therapy, five out of eight subjects no longer met the criteria for PTSD.

Yet, as the number of Iraq war veterans with PTSD grows, virtual reality therapy is still rarely offered as an option. Neither the VA nor the Navy's bureau of Medicine and Surgery, which is conducting the trials for the military, would comment on whether they plan to widen the trials or make it a treatment option for more veterans in the future.

Its advocates remain cautiously optimistic. "The idea was that we used the best technology to train soldiers and to conduct the war," says Rizzo. "Now we need to draw on the best technology to make things right for these folks when they get home."

Shares